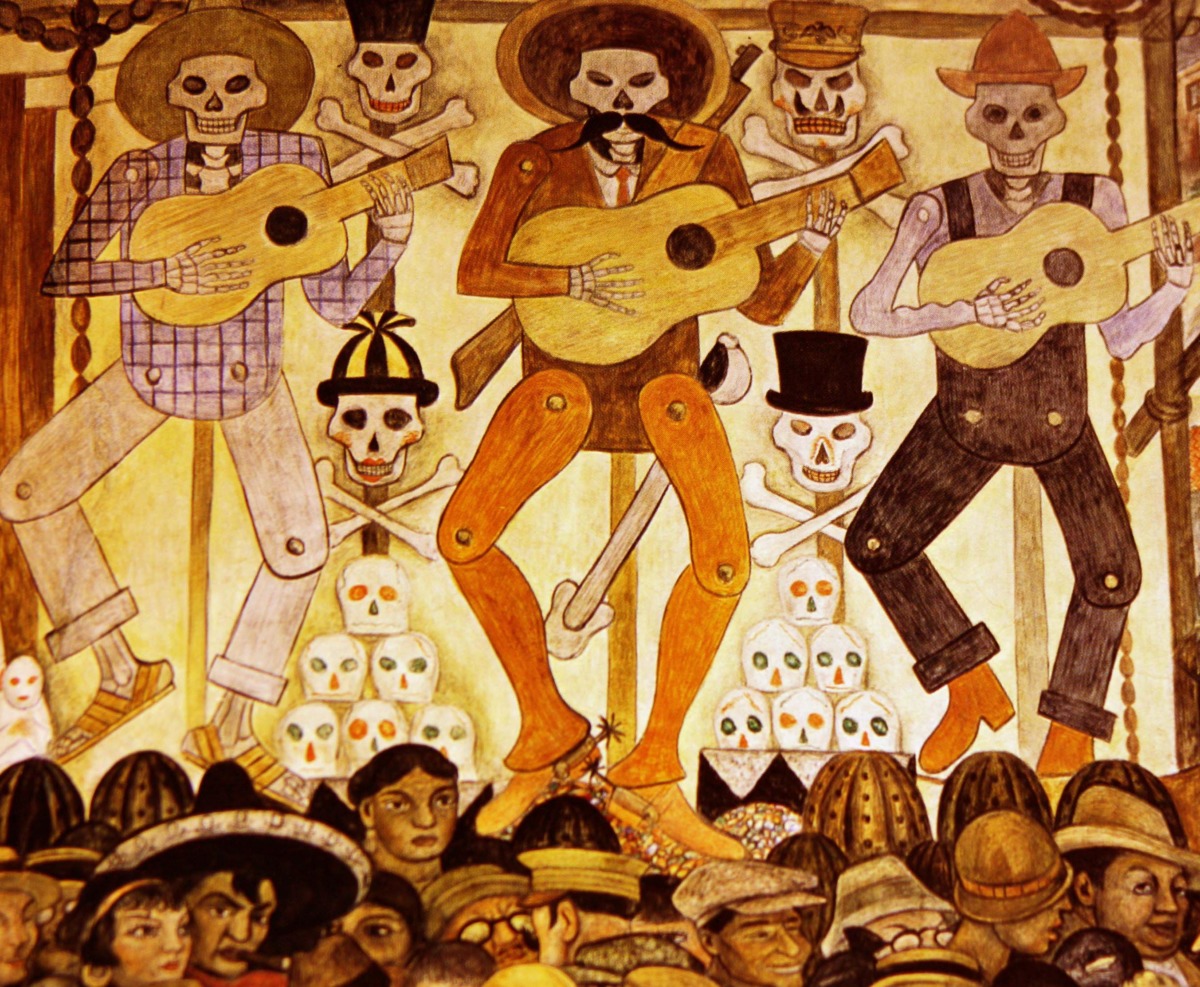

The fall season in Atlanta is always busy with outdoor festivals and parades, perhaps because it is always a welcome relief from the scorching summer heat. The Lantern Parade, the East Atlanta Strut, Dragon Con, Pride, Little Five Points Halloween Parade … these come immediately to mind in what is a rather exhaustive list, but they are only part of a larger international tradition that includes more famous cousins, such as Mardi Gras, Dia de Muertos, Rio Carnival, and the Carnival traditions found in Europe, going back millennia. Today, however, I am thinking of these Atlanta parades in the context of visual culture, and Mikhail Bakhtin’s theory concerning the carnivalesque – the implications of fun time carnival antics can be quite serious stuff, and just possibly of more consequence than the throbbing hangover the morning after.

The Soviets under Stalin didn’t take Bakhtin’s theory lightly. Bakhtin was a bit of a trouble-maker in his day. In 1928, just as his first book was being published, Bakhtin was arrested by the Soviet Secret Police and, without a trial, sentenced to a labor camp in Solovki. His sentence was later commuted to a brief exile in Kazakhstan. In 1940, Bakhtin submitted a dissertation on French Renaissance writer Francois Rabelais for a postgraduate degree. Rabelais’s works are rather bawdy; in Gargantua and Pantagruel he considers the merits and flaws of what might be the best items with which to wipe one’s ass after defecating, before settling on a goose’s neck. In Rabelais and His World, Bakhtin explores concepts surrounding the carnival and the grotesque; the work’s earthy and anarchic suggestions divided his committee. Ultimately the state had to intervene, and Bakhtin was denied his Doctor of Sciences degree, but allowed to keep the consolation prize of candidate.

Bakhtin describes carnival as a social institution, a culture defined by folk-humor, a temporary space where everything is permissible, except, arguably, violence. Carnival is a time of excess, occupying the space between art and life. It is a transitional space, constantly in flux.

Boundaries are tested and blurred: actor and audience, public self and private self. As an alternative social space, carnival is characterized by freedom, equality, and abundance. People with normally silenced voices may feel themselves freer to speak. During Carnival, social conventions are broken and hierarchies turned on their head. In ages past, monarchies and clergy were mocked, and a fool might be crowned for a day, perhaps made the king of a parade. All of this carries an air of celebration and laughter, a celebration of our postlapsarian corporal existence, and laughter, perhaps, at the expense of our social betters.

Mardi Gras, Rio Carnival, and Carnival traditions in Europe have a basis in Christianity; Carnival being the brief time of plenty before the liturgical season of Lent. But from the anthropological perspective, Carnival has deeper roots. Carnivals tend to happen during the more transitional seasons of spring and autumn. In the beginning, Carnival’s frenzy may have been designed to shake loose stagnant winter spirits and usher in the creative energies of spring. In the case of autumn, Carnival could be cause for bringing a community together to celebrate a good harvest, a respite from the doldrums of working fields in oppressive summer heat, and one last hurrah before settling into the sober darkness of winter.

Metaphysically speaking, Carnival is a bringing down to earth, away from the tyranny of transcendent and heavenly thoughts, sober thoughts concerning places ever so achingly out of reach. In carnival, thoughts of spirituality are replaced with spirits of a different sort. Emphasis is placed on the body and the things that make us human. Orifices and the scatological are emphasized: eating, drinking, shitting, pissing, fucking, giving birth. Carnival is a time of transition, and orifices, considered abstractly, are transitional portals through which things must pass.

“Dost thou think, because thou art virtuous there shall be no more cakes and ale?”

William Shakespeare, Twelfth Night (2. 3. 115-116)

Rabelais is not the only author or artist to make use of the carnivalesque. The carnivalesque is practically a staple in art and literature. Embodied as a fool, the carnivalesque character is stock material in Shakespeare’s plays: Sir Toby Belch and Sir John Falstaff being perhaps the most famous — and the most sauced. The carnivalesque in art and literature provides what is missing from the sanitized, romantic, sublime, idealized, or officially sanctioned “reality.” Carnivalesque artwork brings down the high and raises up the low. Nothing is sacred. Hierarchies are reversed, if only for a short time. The carnivalesque in our lives might be like the brief comic relief scenes found in a Shakespearian tragedy, or maybe like the unexpected bit of bathroom stall graffiti, breaking up a mundane afternoon. Bakhtin’s carnivalesque can also manifest itself in grotesque and abject art. The grotesque and abject might lack folk humor-wisdom, but this is compensated with an emphasis on the body, its blurred boundaries, and the scatological.

Consider then, medieval grotesque sculpture, particularly the gargoyle, creatures that are in transition between man and beast, spewing out rainwater. Dramatist, actor, and artist Antonin Artaud provides a modern example; his visual work focuses on the scatological aspects of humanity … blood, urine, semen, excrement. Artaud’s writings on the “Theatre of Cruelty” could also conform to carnivalesque theory, in that its focus is on breaking down the fourth wall, the boundary between actor and audience. Artaud’s works in the early 20th century can now be seen as precursor to the countless examples of later performance artists operating within the realm of the scatological, such as the Viennese Actionists or Carolee Schneemann and her 1964 artwork cum Dionysian ritual Meat Joy.

“Human Salvation lies in the hands of the creatively maladjusted.” Martin Luther King, Jr.

Bakhtin further explores carnivalesque social spaces, our festivals and parades, through a political lens. In Medieval Carnival, monarchy and the clergy were targets of transgressive folk humor. Today it might be big business and elected officials. Carnival, then, is a natural breeding ground for political activism. Conversely, political activism is also a breeding ground for the carnivalesque. And in Carnival, nothing is sacred … We can consider the Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army, who have used humor to diffuse tense situations while at the same time protesting such events as 31st G8 Summit, or the Laboratory of the Insurrectionary Imagination, whose eighth experiment, The People vs The Bankers, involved challenging Royal Bank of Scotland employees to a snowball fight, or the Bread and Puppet Theater, whose 55-year-long history of participating in protests range from protests against the draft during the Vietnam War to later military actions in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Street theater and performance have always been effective tactics used in carnivalesque political activism, but newer tactics devised by Guy Debord and the Situationist movement of the 1960s took the carnivalesque to a whole new level. Dérive encourages spontaneous happenings where large groups of people get together to create a sort of psychogeography in order to combat urban malaise and boredom, in other words, create the carnival atmosphere that can spawn revolutionary action.

Détournement involves taking the symbols produced by those in power, and stripping them of their power; hegemonies are in part held in place by the symbols they produce. Through parody, détournement strips these symbols of their power, and thus the power of hegemony that produced them. Examples of this in the art world would be the street art produced by Banksy and the culture-jamming work of the Billboard Liberation Front. Culture jamming comes from the term radio jamming, where public radio frequencies can either be pirated for subversive communication, or where dominant radio communications can be disrupted, or “jammed.” Culture jamming usually involves pirating public advertisement, and changing their meaning to make anti-consumerists statements.

“Things are tested and reevaluated in the dimensions of laughter, which has defeated fear and all gloomy seriousness. This is why the material bodily lower stratum is needed, for it gaily and simultaneously materializes and unburdens. It liberates objects from the snares of false seriousness, from illusions and sublimations inspired by fear.”

Mikhail Bakhtin, Rabelais and His World, 1965.

Critics of Bakhtin argue that as an instrument of change, the carnivalesque has been historically ineffective. Carnivals allow people to blow off steam, but typically not much more, and although rebellions have been spawned from the festivities, they rarely effect widespread political change. This may be due in part to the temporal nature of Carnival, which, by definition, is not a social space meant to endure for any great length of time. But this doesn’t mean that the state and large corporations have a relaxed, live and let live attitude toward carnival.

Carnival can be subverted through state and corporate sponsorship. The large numbers of sponsors investing big money in Pride parades has become controversial lately. Capital Pride, in DC, even has Northrop Grumman as a sponsor, which doesn’t sit well with many in the LGBTQ+ community. Professional sports (NFL, MLB, NHL, NBA, and Major League Soccer), while not exactly a carnival, but nonetheless a large group of people gathered to participate in a spectacle, received millions of dollars from the Department of Defense, by way of taxpayers, to produce patriotic pageantry and marketing gimmicks for the military. According to the 2015 joint oversight report released by Senators McCain and Flake, the paid for patriotism included “on-field color guard, enlistment and reenlistment ceremonies, performances of the national anthem, full-field flag details, ceremonial first pitches and puck drops.” Arguably more disconcerting is a crowd control tactic called kettling, employed wherever a carnivalesque protest situation is judged to have the potential to get out of control. Kettling involves containing a large crowd on all sides with police in riot gear, limiting free movement.

Bakhtin himself argues in Rabelias and his World that the transgressive power of the carnivalsque has been in decline since the 18th century. And while carnival is by definition a temporary space, subject to ebb and flow, the carnivalesque spirit behind it is eternal, surviving in the creative spirits of artists. As long as there are artists and other creatives, Carnival and the carnivalesque will live on. And it should, regardless of political effectiveness. When we celebrate our corporeal nature, our human follies and missteps, when we celebrate our lower instincts along with sublime aspects of our humanity, we celebrate wholeness of being. It means living without fear and without shame, it means being a complete and honest human being. It means being proud to let one’s freak flag fly.