“For the Constructivists, social condensation was about filling architecture with a sort of revolutionary political electricity. As theorized, designed, and built, the Social Condenser was to be an architectural device for electrocuting people into a communist way of life”.

—Michał Murawski and Jane Rendell, “The Social Condenser: A Century of Revolution through Architecture, 1917-2017”

The cinder block, or concrete masonry unit, is a standard size rectangular block used in building construction. It is composed of cast concrete, industrial waste, sand, and gravel. Technological advancements in the production of reinforced concrete occurred largely in Yugoslavia’s postwar modernization efforts.[1] Structurally strong, low cost, and mechanically uniform, concrete became a defining element of brutalist architecture, meeting both the aesthetic and ideological standards for affordable mass housing and civic structures. The architecture and public spaces that emerged in Yugoslavia during this period (1948 – 1980) were intended to materially manifest socialism’s aspirations of radical pluralism and idealism.

On view through October 27 in the exhibition “MixTape” at Nashville’s Zeitgeist Gallery, Vesna Pavlović’s photographs of performative activism in Belgrade during the 1990s are parenthetically framed by such utopian ideals. Comprised of photographs, installations, artifacts, and built environments, “MixTape” depicts historic and recurrent forms of public activism and cultural performance at the time of Yugoslavia’s dissolution. Pavlović’s photographic practice is characterized by material and social reexaminations of photographic modes of representation, particularly in relation to her own personal photographic archive. “MixTape” continues the artist’s critical and material expansion of photography beyond frame, format, and narrative, but it also considers how technologies—cameras, boomboxes, and cinder blocks—shape social practice.

As its title indicates, “MixTape” is, both curatorially and artistically, an assemblage of disparate parts. The exhibition’s primary components are Pavlović’s personal photographs taken in Belgrade during the 1990s, when EU sanctions against Yugoslavia were in effect. Photographs from Pavlovic’s Women in Black series document various performance-manifestations by the feminist, pacifist collective of the same name. The Circle (1994),a photograph from that series, depicts a group of women lying in a circle on the ground of a public square; a ring of sunflowers, an expanse of cement, and a distant mass of political actors further encircles their bodies. The series Protests 1996 – 1999 documents the actions of peaceful protests by Belgradian students and citizens in response to attempted electoral fraud by the Socialist Party at that time. Return Them Their Picture (1996), a photograph from the Protests series, visually immobilizes the faces of police in the reflection of mirrors held by artists protesting their blockade of the city. Similarly, in Makbet/One (1996), the antic bodies of actors Sonja Vukicevic and Slobodan Bestic are shown performing wildly in front of a police cordon, surrounded on all sides by their audience of fellow protestors.

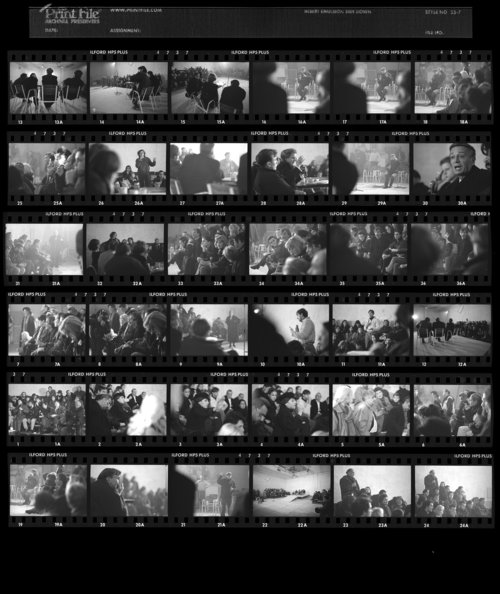

Photographs documenting a public conversation organized by the Center for Cultural Decontamination—an independent cultural institution founded to counter intolerance and nationalism in Serbia—unfold across an enlarged, unframed contact sheet of film. Each frame visually narrates participants smoking, gesturing, and listening to a shifting cast of speakers engaged in the public forum. A temporal document of the event’s proceedings—community dialogue—the contact sheet and the images it contains omit the audible content which evades visual record. On another wall, a series of concert images of Nick Cave, the Pixies, and Serbian bands from the same era form a high-key montage of punk concerts. Seemingly disparate from the documentation of social practice performances seen elsewhere in the show, these concert images— like photos documenting the Center for Cultural Decontamination conversation—underscore the convergence of radical performative actions transpiring across communities, on the radio, and in the streets.

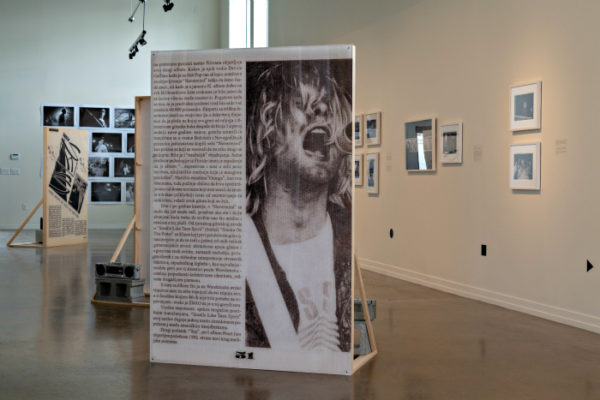

Five large photographic stands interrupt the gallery space. Efficiently built using industrial wood, the fronts of the stands feature enlarged images of photocopied newspaper pages depicting The Smiths, Nirvana, Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, and Sonic Youth, all culled from early nineties Serbian music coverage. Wall-like in stature and similar in appearance to advertising islands, the photo stands function as quasi-brutalist blockades, architecturally negotiating the viewer’s experience of space. These photographic stands commemorate the specific post-punk spirit of these musicians, generally characterized by a commitment to radically new approaches content and form, a refusal of distinctions between high and low culture, an imperative of constant change, and a preoccupation with alienation—all of which are anthemic themes in Pavlović’s photographs of a socially polemic, globally isolated nation. Stylistically, Pavlović refers to this as an “aesthetic of resistance.”

Throughout the exhibition, Pavlović alludes to the conceptual framework of the mixtape. Found boomboxes displayed atop cinder blocks form a sort of techno-structural tableau against a wall, while the back corner brace of each photo stand is anchored by a single cinder block-boombox pairing. The formal resonance between these two manufactured objects is striking; both are elongated rectangles, industrial gray in tone, uniformly designed with two symmetrical square-like shapes on either side. Beyond their visual similarities, relationships between the social functions of these objects invite further consideration.

The boombox, a device used to transmit and record music from a cassette tape or radio frequency, broadcasts auditory information through space and time. Utilitarian in design, the object creates broadcasts capable of traversing physical as well as auditory spaces . The cinder block, conversely, is an elemental object in structural building, often serving as the foundation of built environs, composing a mediating body. Given the extensive use of concrete in Belgrade’s socialist reconstruction period, the cinder block poeticizes the built environs in which social practice takes place. Both boomboxes and cinder blocks display functional and aesthetic priorities of socialism: uniformity, modernity, and an emphasis on communal or public use.

In light of Pavlović’s rejection of the “photographic moment” and her interest in the material expansion of the conceivable photographic “frame”, the inclusion of these various objects and use of these visual strategies are best understood in terms of their indexicality. The boombox is capable of filling architecture with the revolutionary political electricity of radical punk performers; political and social resistors in 90s Belgrade filled architecturally defined public spaces with their bodies; Pavlović’s camera fills the photographic frame with socio-cultural performances of resistance.

In “MixTape,” Pavlović doesn’t provide a journalistic document of social unrest but rather curates an emotive, individualistic visual “mix” drawn from personal and collective archives. Provided the irregular play/eject/stop/rewind cassette player icons that form a border along bottom of the gallery walls—which incidentally subvert the viewers traversal through space—it becomes clear that these political and social histories are active revolutions—recorded, rewound, re-mixed, played forward.

[1] Petrovic, Dragana. “Prefabricated Construction in Former Yugoslavia: Visual and Aesthetic Features and Technology of Prefabrication.”