While I was in grad school, it was a running joke that artists in the MFA program frequently worked with mediums outside their designated department: a friend in the sculpture department became preoccupied with dying velvet; another in the printmaking department devoted himself to large-scale metal assemblages. It became predictable for someone to say, “I consider my paintings sculptures.” As the artist Pat Steir explained to ArtNews back in 2005, “Of course, you can do a painting with a pencil, as Cy Twombly has. Then there are Warhol’s urine paintings. Does that mean the image is the painting? No, because we have Ellsworth Kelly, where the image is a color, or Christopher Wool, where the painting is a word.”

On view at the North Carolina Museum of Art, Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting is a group show featuring, according to the wall text, “some of the most relevant and engaging painting being made in the state.” In the opening lines of the exhibition text, the curator—Ashlynn Browning, a painter based in Raleigh—creates a dilemma for herself. “Throughout modern art history, painting has been declared dead and later resuscitated so many times that the issue now tends to largely be ignored. Despite any debate over painting’s viability, artists continue to persevere in keeping the medium fresh and new.” Browning is right—the “issue” of whether painting is dead is largely ignored because there is no need to maintain categories. As the professor and curator Robert Storr has argued, “For an increasing number of artists, the very game of stretching definitions is the substance of the work.” That’s not to say artists aren’t making paintings anymore—they are, and some of them are even interesting!—but whether or not painting as a genre is relevant misses the point, because genres themselves are largely irrelevant. But, by recalling this debate, Browning resuscitates it.

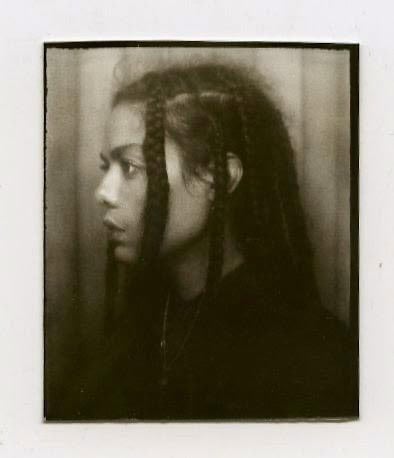

The ambivalence between an exhibition beholden to art history and one that looks to the future is evident throughout the show. The exhibition’s entrance features a trio of muted canvases showing abstract shapes. I turn to the right: in front of me, a painting of colorful rectangles. Behind me: a grid of painted geometric assemblages. I look down the line of canvases on the wall and see paintings that look like other paintings; the exhibition is overwhelmingly familiar. At every turn, more geometric abstraction. There is only one figurative painter in the entire show, William Paul Thomas, whose trio of portraits look lonely in a sea of abstraction. Only a few artists work outside the confines of canvas and paint. There are thirty-six artworks in the show, but it feels much smaller.

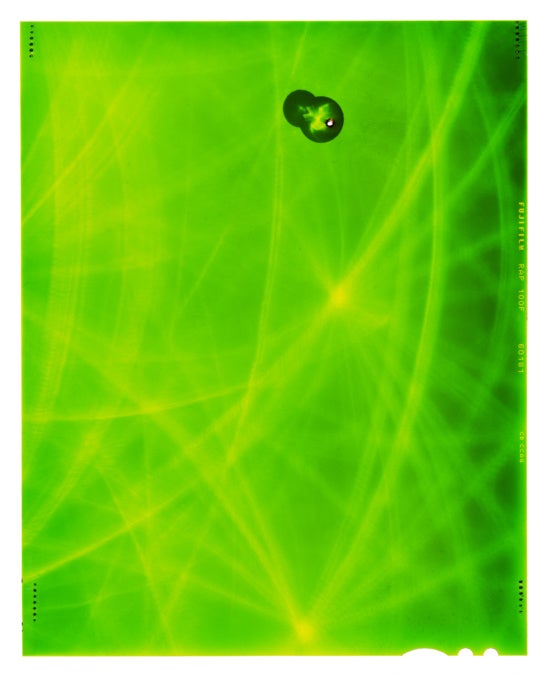

This sameness has a dulling effect on the more interesting works in the show, and only a select few actually felt innovative: Katy Mixon’s Cathedral Window is a quilt made from vibrant scraps of cloth used to clean her paintbrush. Mario Marzan’s acrylic and graphite work Environmental Identities no. 5 is a colorful spatial study whose precise draftsmanship and street art sensibility feel very current. Antoine Williams’s anti-portrait Portrait of a Super Predator Who Died of Student Loan Debt is formed by what the artist calls “acrylic skin,” made by ironing together acrylic skins and gel transfer skins. The effect is disturbingly fleshy.

For a show that is meant to be forward-thinking, the text on its wall labels are laden with art history. The litany of references includes Matisse, Klee, Balthus, Cubism, the Bauhaus, Abstract Expressionism and “the mark,” plein air landscape paintings, Romanticism, Asian calligraphy, Arabic script, Hermann Hesse, and Richard Strauss. Despite such a range of influences, a disappointing homogeneity pervades the works on view. As a whole, the insights on painting that Front Burner offers—abstract painting relies on intuition, the painting process often involves layering paint—aren’t exactly new or novel.

The paradox of this show is that it relies on endless historical references in order to argue for its currency, why its contents are sufficiently relevant. If the curatorial vision is meant to be historical, why not lean into that premise and show works by a variety of painters who are engaging with histories other than Western modernism? If you are going to suggest that painting as a discipline has evolved beyond the use of paint, why not say it with your whole chest and trade out some of the geometric abstraction for something different? Instead of the small wooden geometric abstractions that are on view, Martha Clippinger’s stunning textiles demonstrating her mastery of color play come readily to mind. And, for what it’s worth, affixing four small pieces of wood to the wall is not enough to make it an “architectural installation.”

Painting shows are still possible: within the last year, the Harvey B. Gantt Center in Charlotte hosted the group show Painting Is Its Own Country. Curated by Dexter Wimberly, the exhibition included an incredible variety of paintings that appeared wholly original. Ultimately, Front Burner seems more interested in showing how it was shaped by (a somewhat limited) history than it is in showing how it might shape our future.

So why all this sameness? There are twenty-five emerging, mid-career, and established artists presented in Front Burner. The median age of the artists in the show is forty-five. The youngest artist in the show is thirty-five year-old William Paul Thomas from Durham, North Carolina. This fact, coupled with Browning’s inclusion of her own painting—unsurprisingly, a geometric abstraction—makes me wary of the curatorial selection process for the show.

I have to believe that more interesting paintings are being made in North Carolina, despite what is on view here. Or maybe the best art being made in North Carolina isn’t painting, and that’s okay—painting doesn’t need to be saved.

Front Burner: Highlights in Contemporary North Carolina Painting is on view at the North Carolina Museum of Art in Raleigh through February 14, 2021.