On its surface, Travis Somerville’s exhibition “American Rhetoric” is simply about race. That would be a simple, and sadly simplistic, way to view the 12 works in a variety of media—painting, sculpture, works on paper—that fill the space. Born in Atlanta but based in San Francisco for over two decades, Somerville begins with identity, but his is an identity that is multifaceted, an identity that is constructed far more by interrelationships and expectations than it is by simple attributions of black or white. “American Rhetoric” is the most recent of an ongoing series of exhibitions that force issues of racism, colonialism, expansionism, and imperialism into uncomfortable juxtapositions with Southern culture, politics, and history.

The exhibition begins with four works on cotton-picking sacks, three in graphite and one in oil. Intriguingly, the three graphite works all depict African American subjects, while the oil, titled Independence Day, depicts a young Caucasian girl holding a flag and a gun. The three graphite pieces, all from Somerville’s “Narrative Structure” series, are delicate, almost monochrome images, slightly larger than life size. Drawn from WPA images of African Americans, Narrative Structures 1 and 2 evoke wonder about the specific lives of the subjects. Were they related, and if so, how? What were the circumstances of their lives? Hung at eye level, the works are immediate and engaging, the stained cotton-picking sack of their ground signifying a complex history.

Independence Day, on the other hand, almost suggests a Heath Ledgerian Jokerish character, a dark, sinister, complexly painted, incredibly detailed representation of potential violence. This perception is further reinforced by the gasoline can suspended above the girl’s head and the automatic pistol in her hand. While Narrative Structure 1 through 3 seem pensive, Independence Day seems dangerous, juxtaposing the historical past with the incendiary present. This, of course, in Birmingham, a city still struggling with and reconstructing its own complex past, which gives this exhibition its own more subtle background against which every viewer must consider each work.

The Big Show, a group of seven portraits bounded by what could be read as minstrel gloves or disembodied Mickey Mouse hands, continues the (possibly unintended) oscillation between horror and graphic novel. Here, Somerville transforms anonymous mug shots from the 1920s and 1930s into things of beauty. Their crimes are unknown, but the inference in the context of the exhibition is implied. Their “blackface” is camouflage and disguise, but it is also a mask. Out of context, it is as if Somerville is depicting a series of superhero masks from Stan Lee comic books, and in many ways this reference may not be entirely unintentional. Not, of course, in the context of the superhero but in the idea of the mask. Somerville reminds us that even when not truly hidden, it was and is possible for people’s identities to be concealed. The large hands Somerville uses appear to place his cast in a minstrel show, an idea that is reinforced by the title. But this reading is too simplistic. Somerville is not referring simply to a minstrel show but to the entire construction of race relations.

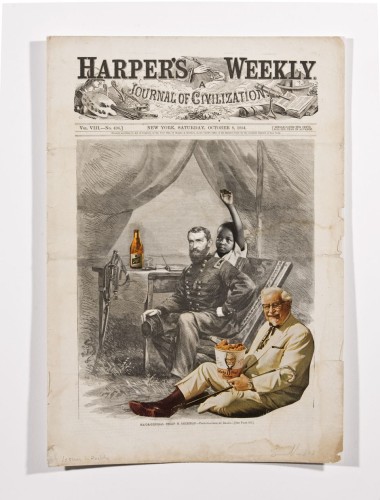

The “Harper’s Weekly” series, constructed by collaging elements onto vintage weekly covers, is one of the more intimate elements of the exhibition. Taken individually, each explores a unique element or aspect of culture or identity. Unchained Melody juxtaposes a young African American girl in a ball-and-chain leg shackle with a photograph of a young white boy holding a watermelon. A bottle of Old Crow anchors the lower left corner. One might consider the double entendre of the title and the song’s lyrics: “and time goes by so slowly / and time can do so much / are you still mine?” Of course, this is not what the song intended, but Somerville shows us how poignant and utterly unexpected it can be when decontextualized.

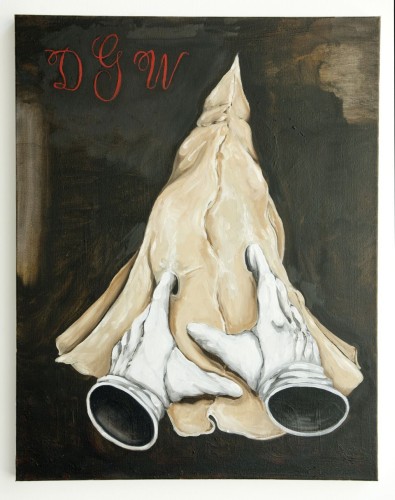

Perhaps it is better to simply read the series cinematically so that you begin with William Tecumsah Sherman, the “most hated man in Atlanta,” as Harper’s Weekly kindly informs viewers, and end with a pensive Lyndon Baines Johnson looking back over the history that is displayed. While Somerville relies on certain representational tropes—a watermelon, Colonel Sanders, buckets of fried chicken, the Kennedys—there is no apparent direct reference to one of the more intriguing threads the issues of Harper’s Weekly display. There, just below the image that contains the Colonel, we see the words “Photographed by Brady,” bringing the entirety of both the historical and the photographic machine, the industry of imagery and materiality, of repetition and representation, of the cottage industry of death that Mathew Brady literally created, onto these images that almost demand to be viewed sequentially. If one then uses Producers Row as a period, or even a coda, one draws in D.W. Griffith’s legendary film Birth of a Nation with, as some viewers thought, its racism masked by its technical prowess.

Somerville, of course, offers Griffith no such respite—in the painting a Klan hood is again grasped by those doubled minstrel/Mickey Mouse hands, and it looks almost as if the Invisible Man is poking the Klansman’s eyes out. One could then take the work to an even deeper and more complex level, one in which Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man stands in the place of those gloves and in fact it is the signifier of blackness that is trying to blind the discrimination of Griffith’s seminal early film.

This is the unspoken complexity of Somerville’s works, over and over, again and again. It is not so much just a simple uncanny reaction to troubling juxtapositions of image and object, of the realization that, in fact, he has painted on something that someone else might have valued more for what it is. It is as if Somerville has no sense of nostalgia, and in many ways he does not. His is an image making that is simply steeped in historicity, but it is not entombed by history. His works begin with a knowledge of history, but he is not necessarily interested in depicting it with any sort of narrative veracity. This is not documentary painting.

One work that deserves special consideration is The Love That Forgives, an installation consisting of four small wooden school chairs, each depicting one of the four little girls lost in the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing. The work, not present at the opening, was added by the artist as a coda, completed in a burst of creativity when he understood how to use the chairs he had collected some time ago. Now, set low on the floor, near the window, they anchor the exhibition, bringing a local context and a heartbreaking immediacy to what is already a moving yet not altogether somber show, drawing the work’s title specifically from the title of the sermon that was to be delivered on that tragic day.

Below the surface, “American Rhetoric” is about the many issues that surround the problematics of race. On the surface, race simply serves as the out, as the way to escape delving deeper, considering issues more closely, thinking in more complex ways. If Somerville is constructing a rhetoric, it is for an America that is both cemented within and trying to revise its history at the same time that it mistakenly believes it is jettisoning its past for some homogeneity of “today.”

Travis Somerville’s “American Rhetoric” is on view at beta pictoris in Birmingham through May 30.

Brett Levine is a writer and curator based in Birmingham.