a special edition prototype, 2014; paper scraps, reused mat board and foam core, discarded

bundle string, cigarette package foil, copper wire, straw, fabric scraps, thread,

discarded coffee filters. (All photos: Erica Ciccarone)

Art made from refuse can go one of two ways. It can look like it’s pasted together from the leftover scraps of 7th period art class, lacking composition and concept. Or, if we’re lucky, it can be conceptually rich, using materials in distinct, purposeful ways that allow them to tell the story of their lives as objects in the world.

The latter seems to be the inspiration for “Paper, Thread, and Trash,” an exhibition of works by 14 Tennessee artists on view at the Nashville Public Library through March 29. Artist Courtney Adair Johnson makes her curatorial debut with this collection of books made from reused materials. While many are actual books—some tiny and intricate, others spread wide across the gallery walls—many are conceptual, playing on our ideas about narrative, memory, and consumption.

Although there are a few low points, the exhibition is innovative and memorable; it’s quite an adventure to make your way through the roughly 60 interpretations of the theme. Johnson accepted several works by each artist, including wall pieces, sculptures, and installations. The approaches vary, and many are full of text. The only problem is that we can’t read them because they’re protected by display cases, which is an issue for any show exhibiting artist books. The meticulous, poetry-infused books by Nelson Meadows, for example, seem to promise something they can’t deliver when trapped behind glass. Similarly, Cynthia Marsh’s chunky, block-printed letters essentially tease the viewer, because we can’t read anything beyond the displayed pages.

But, the pieces we can fully engage with invite a wealth of imaginative interpretations. Lesley Patterson-Marx looks for implied narratives in objects she finds, tapping into our collective cultural memory. Here, she transformed a transistor radio into a book filled with collected stories from people who remember using the device. Emily Holt only used materials she gathered while walking her dogs, thereby creating a neat ecosystem of her neighborhood.

Aletha Carr assembled pieces of discarded book covers into geometric abstractions, suggesting a possible outcome for the books we love after they leave our hands. M Kelley’s The Quantifiable Unknown collects pieces of her artistic practice. She tracked her daily mood for six months, mapping her emotional state each day. She also added the Zen Buddhist practice of ensō, painting a single two-stroke circle on a reused paper bag each night. In the process, Kelley made the personal choice to distance her happiness from her circumstances.

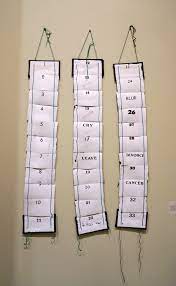

I’m already a fan of Johnson: she works exclusively in reused materials, layering and painting in a way she says is spontaneous but looks carefully composed. There was plenty of this, but my favorite of the curator’s is My Years, a wall piece that chronicles major events in the artist’s life. She marked index cards with letraset transfers for each year, indicating years that have special meaning: cry, leave, divorce, cancer. It reminds me of how we construct our life stories to reflect our dominant tragedies, and I paused to consider my own years in between them.

Nance Cooley’s One-Tie-We All Tie seemed to garner the most attention at the show’s busy opening. Cooley used cardboard and foam board to construct two figures that sit at a table, both holding long forks that are attached to their arms with ribbon. Made from layers and layers of the cardboard and foam board, they also have facial features and moving joints. It’s a reference to the Allegory of the Spoon, an old parable describing heaven and hell. Cooley wrote a few statements on the table, one being “Intent and outcomes. Resources and consumption. Interdependence.” Although the piece adds a needed focal point in the gallery, the message about interconnectedness is made too obvious and strikes me as sentimental at best.

The job is done much better with Cooley’s mechanical constructions, which require the reader to enter their illusion and articulate the parts in order for the pieces to reach their fullest expression. Some contain text, challenging the way we read and the level of our engagement. To read them, one must be open, curious, and anxious to see what unfolds.

Kit Kite took to the theme with the most conceptual approach, showing work from the X Housewife Portraits. In the series, she examines how the “trappings of domesticity” became quite literal over the course of her marriage. Object X is a house only big enough for one person at a time to view the film playing inside. In the film, there’s a succession of close-ups of household objects and a voiceover narrative. In Kite’s carefully staged, large-scale X Install Portraits, she disappears among the objects of the home, as in Forked Over Consumption, in which a mob of silverware pulls her into a drawer, and Backed and Racked, in which a cloak of bakeware and cooking utensils pins her down. It’s not just a dual critique of gender roles and consumer culture; that’s been done to exhaustion. The series really gains ground when we realize that in the photos, Kite is performing as a woman in isolation who longs to connect and who is struggling to define herself. It’s not just for housewives; it’s for anyone who has felt overlooked.

Kite’s sculptural textile pieces are mounted on the walls flanking One-Tie. There are seven pieces total, each inspired by a story read to Kite to as a child. The Wonderful Wizard of Oz (Princess Langwidere) is a sculpture of three white-gloved, many-fingered hands that move as if in the middle of a magic trick, a royal blue velvet ribbon woven between them. These pieces capture the multitudinous worlds of the stories and the personal connections we build with characters. Overall, Kite’s additions to “Paper, Thread, and Trash” elevate an already solid show to one with mystery, resonance, and longing.

We know that objects don’t have actual stories to tell, but “Paper, Thread, and Trash” causes us consider how we make meaning from the stuff that fills our lives.

“Paper, Thread, Trash” is on view through March 29 with artist workshops open to the public.