“The loss of stories sharpens the hunger for them.”

Saidya Hartman—one of this year’s recipients of the MacArthur “genius” grant—wrote this line in her best-known essay, Venus in Two Parts, in which she also coined the term critical fabulation. Hartman defines this as the dual practice of contending with the limited archives and accounts of enslaved people through using narrative speculation to give form to what might have been. In her traveling exhibition Sanctuary for the Internal Enemy, Atlanta-based artist Tina Dunkley has embraced the possibilities of critical fabulation within the context of visual art through a series of multimedia works that pivot around stories about her recently discovered ancestors and what the limited archives have taught her about their lives.

While the War of 1812 was predominately a conflict between British and American forces, it nonetheless brought a number of unexpected allies to join the cause against the United States, including Native Americans, Canadian settlers, and enslaved African Americans—the latter of whom were given the opportunity to leave the United States and settle in either Trinidad or Nova Scotia (then, both British colonies) as free people. Recently, Dunkley discovered that she is a direct descendent of the minority of freed men who elected to settle in Trinidad, forming a small and tight knit community that described themselves as Merikins (a Creole adaptation of Americans). Sanctuary for the Internal Enemy is a meditation on these ancestors and the lives they may have lived.

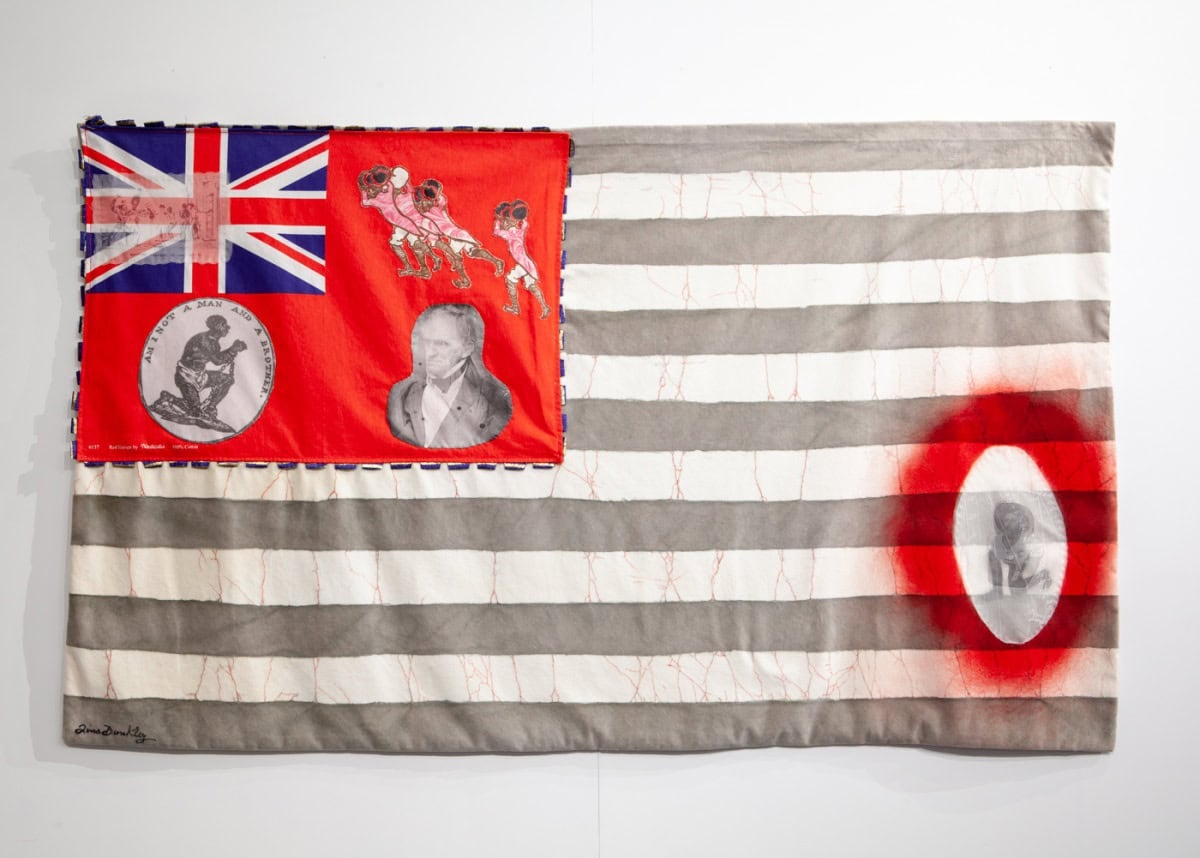

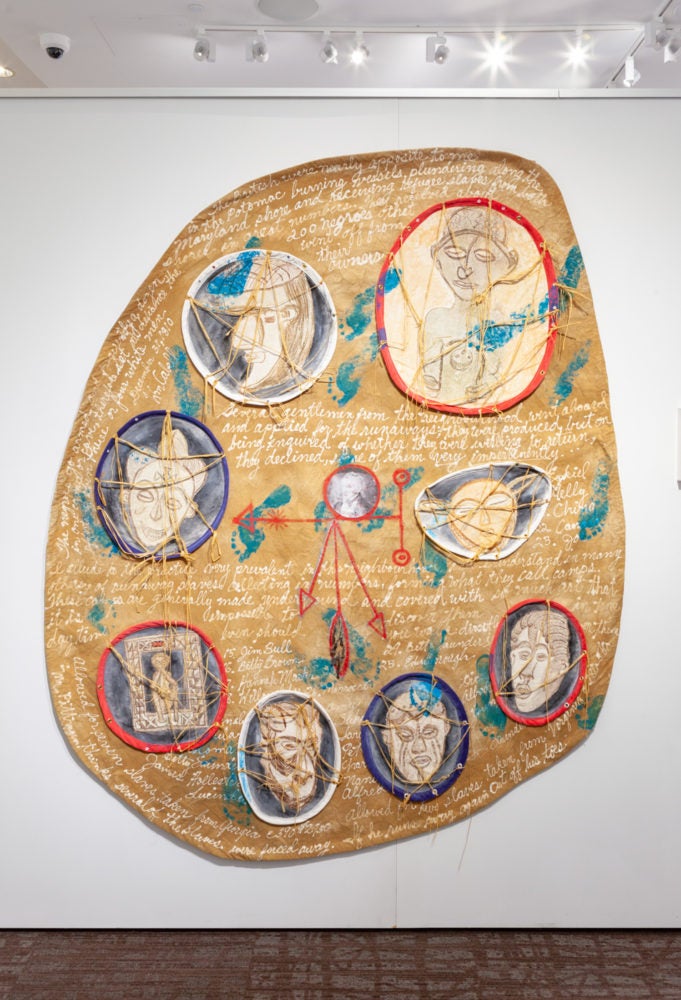

Several works in the exhibition directly pull from documents Dunkley was able to find about her family such as Who is Uncle Boocoosoo? (2012-2018) which reads as a beautifully sewn and well-hewn diagram of the movements of freed slaves away from the plantation owner pictured in the center. Uncle Boocoosoo was, in fact, a great-great uncle of Dunkley’s who was among the early nineteenth-century émigrés to Trinidad. Likewise, in Google Meets Shango at the Ebute Mette House (2018), the material and textual elements of the sculpture directly reference vernacular insignia that the Merikins adorned their Trinidadian homes with for generations once they resettled on the island and were able to openly express their African heritage.

Strip quilting, embroidery, weaving, and other mediums that reference traditional African and African American craft traditions are highlighted throughout the exhibition and function beautifully with the more self-contained framed collaged cyanotypes that comprise the majority of the works in the show. Certain moments, however, feel overly didactic and directly illustrative of the history they are drawn from, such as the numerous reproductions of historical documents that are not used as contextualizing ephemera but rather as material woven into sculptures and prints, giving the impression that the artworks are artificially made to look old. But on the whole, the works throughout the exhibition are able to transform and transmute their inspiration into complex and luscious forms that appear distinctly derived from Black history while also grounded in the material and aesthetic present of the twenty-first century.

By combining references to the nautical and naval passages that brought these families to freedom in the early nineteenth century with Black figuration and early American archival documents, Dunkley recalls the trauma of the middle passage and the inextricable relationship between the African American experience and the almighty void of the Atlantic ocean. Despite this, Dunkley is able to critically fabulate a story of freedom, safety, and family, celebrating her ancestors who were able to escape from American terror and build a new nation of Merikin survivors.

Tina Dunkley’s solo exhibition Sanctuary for the Internal Enemy: An Ancestral Odyssey is on view through Sunday, October 13 at the Auburn Avenue Research Library in Atlanta.