While Chattanooga-based Phillip Andrew Lewis and Los Angeles-based Kevin Cooley maintain separate careers, they occasionally collaborate on larger experimental works that push their collective creativity to intricate ends. Their second collaborative exhibition, “time // lines,” is on view at Zeitgeist Gallery in Nashville through June 25. Their shared interests in technology and the natural world inspired them to build three installations that challenge how time is perceived in everyday life. Their interpretations of engineered, geological, and biological time are reminders that our perception of time is structured with human-made measures. The duo, who met while residents at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Art in Nebraska, has developed a reputation for realizing their ambitious art with rich concepts and exacting technology, and “time // lines” is no exception.

Engineering time is perhaps the most overt way that humans try to control their reality. Hanging from the gallery ceiling, Revolutionary Minute is reminiscent of a giant wind chime with the intricacies of a grandfather clock. The complex sculpture activates through an electric pulse that turns on a fan suspended from the structure. The resulting movement causes the clapper to hit steel pipes and sound the passing of a French Revolutionary minute, 100 seconds. French Revolutionary Time (FRT) was introduced in 1793 as an advanced way to measure a day: 10 hours equaled 1 day with 100 minutes per hour and 100 seconds per minute. While the intent of the new system was to simplify fractions of the day—4:00 indicating that 40 percent of the day has passed—people were not willing to change from the 24-hour days that we continue to use today. Revolutionary Minute addresses the common belief that time is objectively measured, while in truth it is constructed to meet societal needs.

The process of creating an original sculpture to mark FRT — carefully considering the materials, composition, and conceptual aims — was a challenge the team relished. For the clapper that sounds the chime, for example, they had tried using a piece of wood to bang against the steel pipes, but the tone wasn’t right. Through trial and error, they found the best resonance came from a vinyl record, an object that came to mind from their previous collaboration at Zeitgeist. They agreed they were also attracted to the idea of subverting the function of the disc by using it to “make sound, not play sound.” So the duo headed to a record store. Cooley joked that their collaboration includes “a lot of shopping and experimenting.” Hearing that they were looking for a knocker to use in a sculpture, a record-savvy stranger suggested a picture disc featuring Amy Stewart’s famous single “Knock on Wood.” When they installed the record in their mechanical sculpture, they knew the aesthetics, sound, and the added humor of the song title completed the artwork. Cooley says, “everything in the show is minimal, and this imagery is a subtle nod that makes the reading of the sculpture more complicated.”

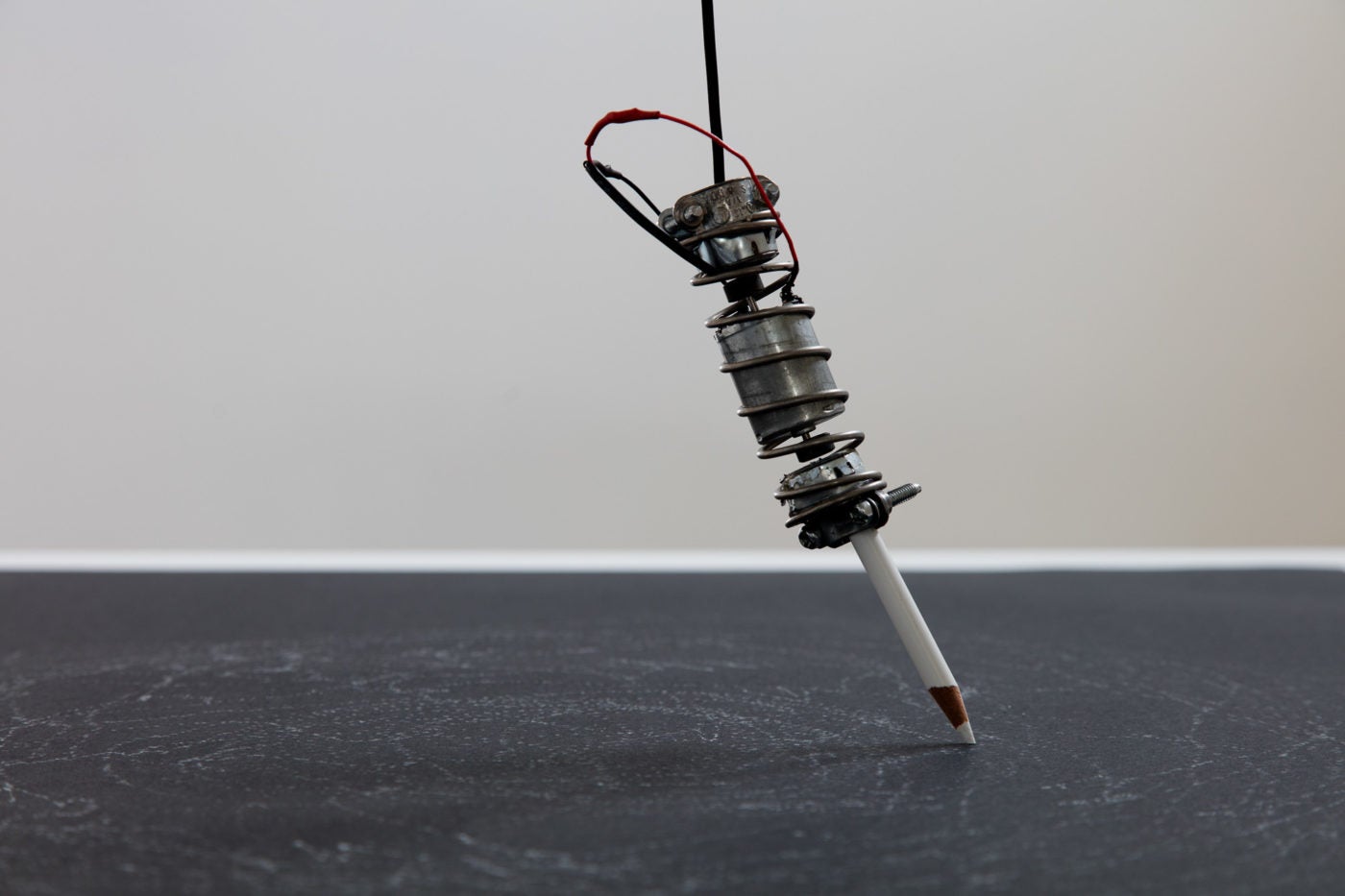

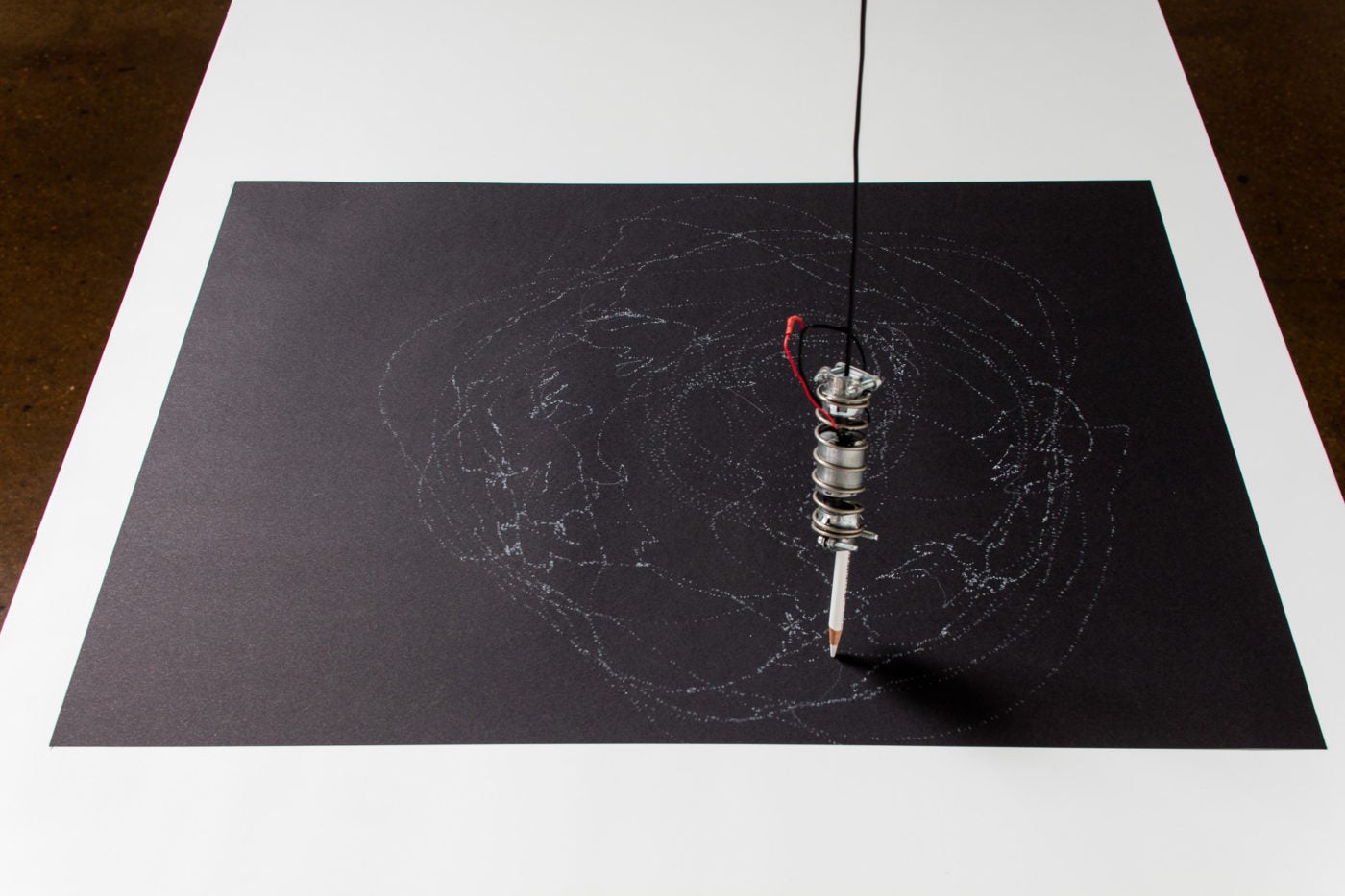

The duo created Seismographic Pencil to depict geological time by marking the earth’s shifting tectonic plates. Living in Los Angeles, Cooley experiences earthquakes frequently, which inspired the artists to find an interesting way to represent daily tectonic movements. Cooley says that they were interested in measuring the earth’s time through seismic activity, including “man-made actions like fracking that affect the earth’s natural movement.” Using their experience with micro-controllers and Arduino technology, they built an art-making machine. The installation includes a robot-like device holding a pencil programmed to move across a blank sheet each time the United States Geological Survey reports seismic activity anywhere on earth. Standing in the gallery, seeing the pencil appear to stop and start on its own evokes the wonder Enlightenment-era viewers surely experienced while watching automatons.

The resulting minimalist drawings, which they call Seismograms, translate the invisible seismic activity of the day into white marks on black paper. The more tremors, the longer the lines and more expansive the resulting composition. On days with little geological movement, the drawings appear dotlike and compressed. Lewis says, “the forms created by the Seismographic Pencil—long lines and circular patterns—are made using the same seismographic data scientists use to create traditional linear graphics that read left to right. We wanted a more complex reading, less about the specifics of numbers and places, more about the accumulation of activity across the earth’s plates.” The first Seismogram was produced at the “time // lines” opening on May 7. Gallery director Lain York changes the paper daily so that each Seismogram represents the seismic activity of each day through the exhibition closing on June 25. Both the Seismographic Pencil and the Seismograms call attention to the human urge to comprehend the earth by inventing technology to measure and document it.

Art, biology, and society overlap in Invasive Species to demonstrate that human interventions can also overtake nature. To represent biological time, they began with the single idea of using an invasive plant. They tried honeysuckle, grasses, bamboo, and other plants, but they kept coming back to kudzu. Reading its history, Cooley was taken with the plant. It was introduced to the United States during the 1876 Centennial Exposition hosted in Philadelphia and spread widely during the New Deal period when it became the government-issued means to deter soil erosion. The plan backfired; the aggressive vines grow over anything in its way — trees, fences, homes — covering them like a blanket. A native of the South, Lewis is well aware of the destruction uncontrolled kudzu vines cause and the negative connotation it has regionally. “People have a lot of anxieties about kudzu: it’s full of snakes, it’s dangerous, it’s not something you want to touch.” Selecting a vine rooted so deeply in Southern vernacular had additional interest and meaning in Nashville that they had not considered.

Inspired by the scale of change the plant can create over time, Cooley and Lewis developed a sculpture made of live kudzu and chain-link fencing to recall the undulating shapes of overtaken fields. The process of working with a living plant presented challenges that proved meaningful for the sculpture. Lewis collected dormant kudzu and collaborated with members of the University of Tennessee Chattanooga (UTC) botany department to learn what they called “plant time” and how to manipulate it to activate the plant’s growth in time for the exhibit opening. Experts and artists working together to spur nature is just another reminder that even biological time can be changed by human intent.

Time may be constant, but the three inventive installations in “time // lines” prove that measuring its scale is not. The artists’ interests in science, technology, and nature fueled their imaginations and yielded experimental structures that essentially place them within the lineage of artist-inventors who have explored the natural world throughout history. These complex works of art are crafted with detail and aesthetic elegance. Unlike pure tools of science that supply data in a direct way, the artists represent the same information in a nuanced manner that raises questions and challenges expectations. Through their interpretations of engineered, geological, and biological time, the artists subtly subvert common temporal conceptions and provoke conversations about the lines that have been drawn to mark the passing of time.