BY BRETT LEVINE

Black art matters. And yes, at times, within the framework of art criticism the term “black art” should be used specifically because it celebrates and reinforces a lineage that includes innovations as diverse as the Negritude movement that emerged in the 1930s and the scathing insightfulness of Adrian Piper’s Passing for White, Passing for Black essay from 1992. Nowhere is this lineage more apparent than in Sheila Pree Bright’s exhibition “#1960NOW,” on view at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia.

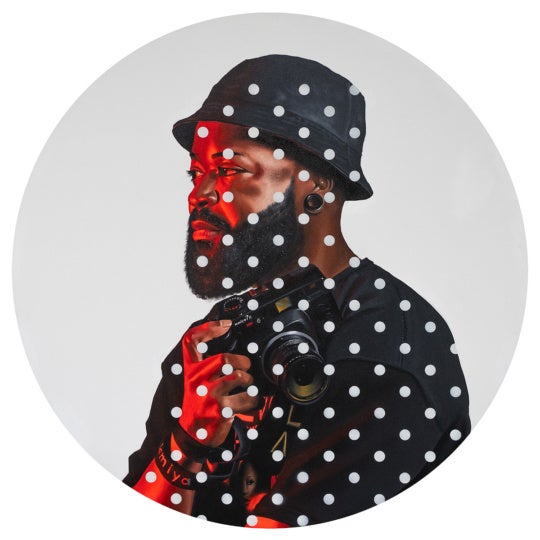

Pree Bright’s project is a complex amalgam of social conscience, social practice and fine art, a hybrid that makes many viewers uncomfortable in its insistence and its directness. This immediacy, which #1960NOW shares with Chris Johnson, Hank Willis Thomas and Bayeté Ross Smith’s Question Bridge: Black Males project, thrusts the universality and the significance of the black experience to the fore. Pree Bright has adhered her subjects’ portraits to the gallery floor—a reference to her eponymous street project, for which she wheatpastes large-scale portraits to disused buildings. There, overlapping, their faces stare up at the viewer, creating the unnerving possibility of stepping on these black activists. Metaphorically, Pree Bright is asserting that this is precisely what happens to them every day within the larger context of society.

The exhibition is participatory. The gallery’s front walls are painted with chalkboard paint, and chalk is provided so that viewers can add their own thoughts and comments. Perhaps it was the context of the exhibition, or perhaps the framework of the space itself, but the texts I saw were uplifting and engaging. One wonders what might have transpired in a different environment, but the sense of engagement generated by the images themselves and by the true sense of participation seemed to mitigate these concerns.

Pree Bright’s focus on emphasizing the contributions of generally lesser-known participants within social movements should be lauded. It was the foot soldiers who formed the foundation of the Civil Rights Movement, and it is those same individuals that Pree Bright celebrates today. Her capacity to link the historical and the contemporary illustrates their interconnectedness. What her images prove is that the movement is not historicized. Nor is it over. Instead, her subjects represent active engagement. Better yet, they represent activism and activists in the most positive senses of the word. One wonders how the terms ever came to have any other connotations.

One unique aspect of the exhibition is its capacity to overwhelm. On the day of my visit, I had the opportunity to experience the videos playing without headsets, their audio reverberating throughout the gallery space. As the two soundtracks began to overlap, and to collide, and certain assertions began to resonate, the space energized and filled with excitement. In that moment, the exhibition truly came alive. For it is as much in the voice, as it is in the image, that the power of Pree Bright’s subjects resides. She has documented their ‘self,’ and given them voice, and as their voices swell and their volume increases it is as if the needs of a compassionate society to consider the issues she addresses were swelling also. In a sense, the exhibition itself resides in that space between this silence and noise, between the voice of each of the individuals and the voice of a larger society, between the capacity of an individual and the capabilities of a group. This is what is inferred by the works written in chalk on the walls, in the positivities inscribed, in the chants and refrains of ‘black lives matter.’ And it is in and through works like these—in which viewers are compelled to consider something beyond aesthetics—that more complex questions of social discourse can begin to be explored.

“1960NOW” is on view at Mason Fine Art through December 31 and at the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia through November 28.

Sheila Pree Bright will give an artist talk at MOCA GA on November 19. Reception at 6 pm, talk at 6:30pm.

Brett Levine is an independent curator, writer, and editor based in Birmingham.