By now the mythology surrounding the Lomax-like “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” curatorial adventure is firmly established: hours spent (many), miles traveled (even more), and artists interviewed (I’m only familiar with that many who’re dead). Fiscally speaking, the endeavor still feels a bit extravagant to me, but I’ve been to the exhibition twice and I’m getting over myself. Don Bacigalupi and Chad Alligood’s mission was noble; undertakings of this nature are normally contained to a specific geographic or cultural region or end at the state line. But remove “unknown” and “underrepresented” from their mission statement, and you are still left dealing with how in the world are you going to represent “contemporary American art”?

I rarely cheerlead at full voice for any exhibition—maybe the last time was a 2007 trip to the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City to see an exhibition of the artwork of Armando Reverón. My curator-as-visitor approach to an exhibition is to balance what doesn’t appeal to me with what does, and to defer to the decisions of curators and curatorial assistants when it comes to the choices of artwork and installation arrangements. “State of the Art” is no exception. I have issues with video artworks whose soundtracks overlap with, or drown out completely, the sound of another video piece nearby, and this happens in three instances in the exhibition. No visitor would have a favorable response to every artwork in an exhibition; I certainly don’t. But taken in its entirety, the exhibition is an exceptional statement to American artistic diversity.

But I would like to cursorily respond to some of the words of detraction I have read. Few exhibitions go unscathed by the public or critics, and “State of the Art” is no exception. That said, some art critics (primarily) dismiss all but a fraction of the artwork in an exhibition as the means of proving their intellectual chops or aesthetic acumen. Others, art critics and general public alike, may be too invested in a particular mindset of what “American art” is or what contemporary art is supposed to look like—from the choice of materials and how they’re used to where the artwork was made—to extend any amount of deference. Some observers, art critics and general public alike, simply made up their mind before getting out of bed that, whatever it is, they won’t like it. Art does not have to be obtuse to be effective, neither does being more gettable make an artwork automatically dismissible. Yes, there are some dark, challenging, and conceptually laden artworks in “State of the Art,” but none of them are in your face. These artworks communicate in quite, subtle—and for that reason—more profound ways. To two critics, Peter Plagens and Christina Rees, specifically I ask, what about Art for Art’s Sake? What about the beauty of method or materials or imagery? Or maybe it’s just that you didn’t get it. Everyone else should go to Crystal Bridges for “State of the Art: Discovering American Art Now” to see thought-provoking artwork by artists exploring materials, environment, culture, and identity. Don’t bother going to if you’re looking for a ride on the coattails of the Whitney Biennial.

Wow. Guess I found my ax.

Because I’m not a full-time cheerleader, let me begin by just yanking some Band-Aids clean off. Among the Southern artists included in the exhibition, the artworks of John Douglas Powers and Celestia Morgan left me unimpressed. Ialu, Powers’ kinetic sculpture (a field of wheat) and video projection (a mirrored loop of cloud and sky moving towards the center of the projection) are overkill in need of an edit. I wanted to like this artwork, I really did. But the piece lacked an embrace (or acceptance?) of the sublime. Go to YouTube and watch Arthur Ganson’s Machine with 23 Scraps of Paper to see what I’m talking about. The video element in Ialu interfered with the actual movement and resulting sound made by the sculpture. The movement and sound spoke to unfelt winds – the sculpture works on its own merit. I may be splitting hairs or pouring salt by making a comparison to Ivan Puig’s Mandala I and Mandala II, but I believe Puig strikes a balance with sound, motion, and the sublime.

Morgan’s black-and-white photographic series Broken, of shadowy figures seen through broken glass, represents the internal pain and struggle that some individuals have survived or live with, whether by circumstance or decisions made. The title of each photograph is a quote by the sitter that obliquely references their situation, giving viewers a glimpse into their lives. Morgan creates a worthy visual communication of her idea, but Broken is a one-trick-pony on par with Intro-level student artwork.

In Guy Bell’s painting, Cain and Abel, two dogs lock in mortal combat in a golden landscape, an ambiguous vehicle approaching in the distance. The landscape is arresting and sumptuous, but I am bothered by the representational quality of the two dogs. The white dog as an example: I see two distinct dogs here, one belonging to the fore legs and upper body, and a second belonging to the mid-section and hind legs. And then there is the stark white, featureless tail stuck onto the shadowed hip. Forgive me, but I don’t see evidence of a stylistic decision. Hands and feet don’t lie—if you can’t draw or paint them, then don’t. Do I make sense when I say that I generally like the imagery in this painting, but I have reservations regarding its inclusion?

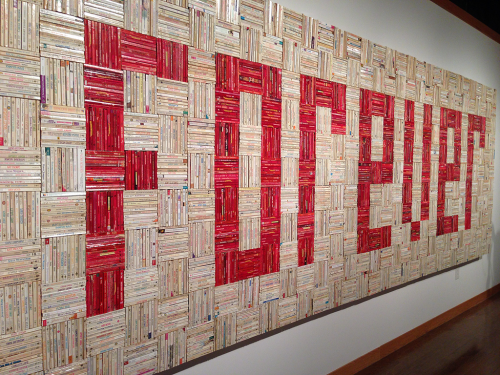

John Salvest’s Forever is a large sculptural mural constructed from red- and white-bound romance novels, spines turned outward to reveal their titles. Salvest has spent many years arranging objects and collections of non-art materials to create subtle plays related to the use of an object to amusing and sometimes ooky conclusions. But Forever is borderline banal, one of those “ideas for artwork” that is more interesting on paper than when fully realized, as is John Riepenhoff’s The John Riepenhoff Experience, a miniature gallery that visitors poke their heads into from below.

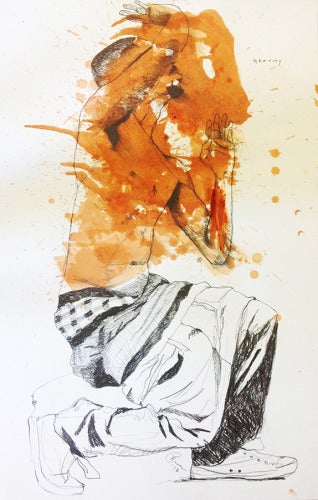

Although the list of works I do like is much longer, I’m choosing to balance four-for-four, what doesn’t move me with what does. Fahamu Pecou’s self-portrait drawing series, Gravity, shows the artist shirtless in saggy pants, splashed terra-cotta washes across his torso, arms, and head. Gravity presents the artist’s struggle as he navigates between pre-fatherhood (old Self) and fatherhood (new Self); a sagger immaturely jumping up and down in anger demanding the world tell him what to do, all the while looking around sheepishly to see if the answer has appeared. My introduction to Pecou’s artwork was through his painted self-portraits on the covers of real and imagined art magazines, painterly in style and full of bravado. With Gravity, the risk is in revealing how vulnerable and forthright he can be.

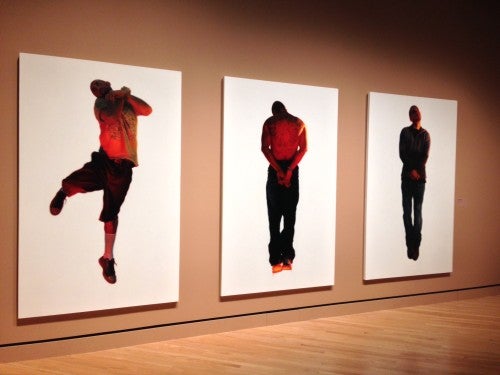

Vincent Valdez’s triptych, The Strangest Fruit, places an emphasis on what you don’t see as the means to communicate what you need to see. Three men each float on a field of white, their bodies glow in the red-orange light of a setting sun or a fire. Two men appear to hang in supplication, the third moves in some dance, a Spandau Ballet? The Strangest Fruit is the stylistic reverse expression of Ken Gonzales-Day’s manipulated photographs (not included in this exhibition) Erased Lynching series (2000-13). Valdez lifts these victims from the scene of their lynching to create an enigmatical and disturbing vision, leaving the viewer to wonder what is happening to these men. It took me a good minute to see past the artist’s beautifully realized figures to horror he is communicating.

I have decided that Stilllives II: Vignette, Dave Greber’s video projection on the floor in a semi-darkened room, has to be the love child of Monty Python and the Banana Splits. Americans live in aural and visual excess, but we’re used to it. It rarely fazes us. In a fantastic way, Stilllives II: Vignette reinterprets that continuous array of discordant imagery and sound. And in an oddly pleasing way, with an overhead viewpoint, random objects repeatedly overlap and replace each other in painterly vignettes. The name I’m coining for that love child is Projectile Fantasticism (and I’m hoping the artist will use it to describe this series of videos—because there are more). On a nearby wall in this same room is Greber’s Sinew-en-ciel, a neo-psychedelic stream-scape made with acrylic paint, rhinestones, and a video projection. It’s candy-colored and intense, but in a good way. An interesting way. A fun way. Only the acrylic paint and rhinestones reflect the colors projected on the black wall. Sinew-en-ciel is like an updated black light poster that I want for my bedroom wall.

(Photo: Dero Sanford)

I like Linda Lopez’s ceramic sculptures because they do nothing and do it well. On a two-tiered mudroom-like table rest three distinct ceramic forms. On the top tier are five golden coral forms awaiting their appropriation into a Lady Gaga hairstyle. On the lower tier are two sets of five matte black objects: two curvy forms are covered in raised dots of varying sizes, and three are Cousin Itt portraits in miniature. If there is a deeper meaning associated with A Moment is Forgetfulness, Lopez is not letting us in on it. Like Greber, she references many things but not in any recognizable manner. But Lopez’s ceramic artwork is a wonderful example of craftsmanship with curiosity.

I love this amorphic, nebulous thing we call contemporary art. I love it because it is every possible voice working in every possible style and in every manner of media. And I appreciate when curators attempt to define a movement within contemporary art—whether it is regionalism or the more grandiose concept of “contemporary American art.” As a museum professional working at a public university, education permeates practically everything I do. So what does it matter if some visitors to Crystal Bridges are stopping off the bus on the way to or from Branson? Because yes, I had a very nice conversation with three grandparents who were confused about a good number of artworks they saw but wanted to talk more about the artworks they liked. I found myself engaged with 80-somethings the same way I engage with 20-somethings. And I found myself really understanding the importance of “State of the Art” and the understanding of what contemporary American art can be.

Nathan Larson spends too much time wandering the halls of the Internet, not always with a hall pass, but usually with the best intentions. He is also the assistant gallery curator in the fine arts department of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (UALR).