“The South has always had something to say.” Entering Ella West Gallery this fall, these words greet me on a black wall with stark white text—a quote from Clarence Heyward, contemporary painter and the curator of their current exhibition, Southern Grammar. This is a take on rapper André 3000’s famous statement at the 1995 Source Awards that “The South got something to say,” which captured the region’s rising cultural influence.

Here, in an exhibition replete with exuberant color and decisive, bold strokes, Heyward reminds us that the South had much to teach us, long before most of the country would listen. He argues this persuasively by exploring the Black Southern experience in the work of three contemporary artists: painters Jō Baskerville and Jeremy Biggers, along with fiber artist Sam Lao.

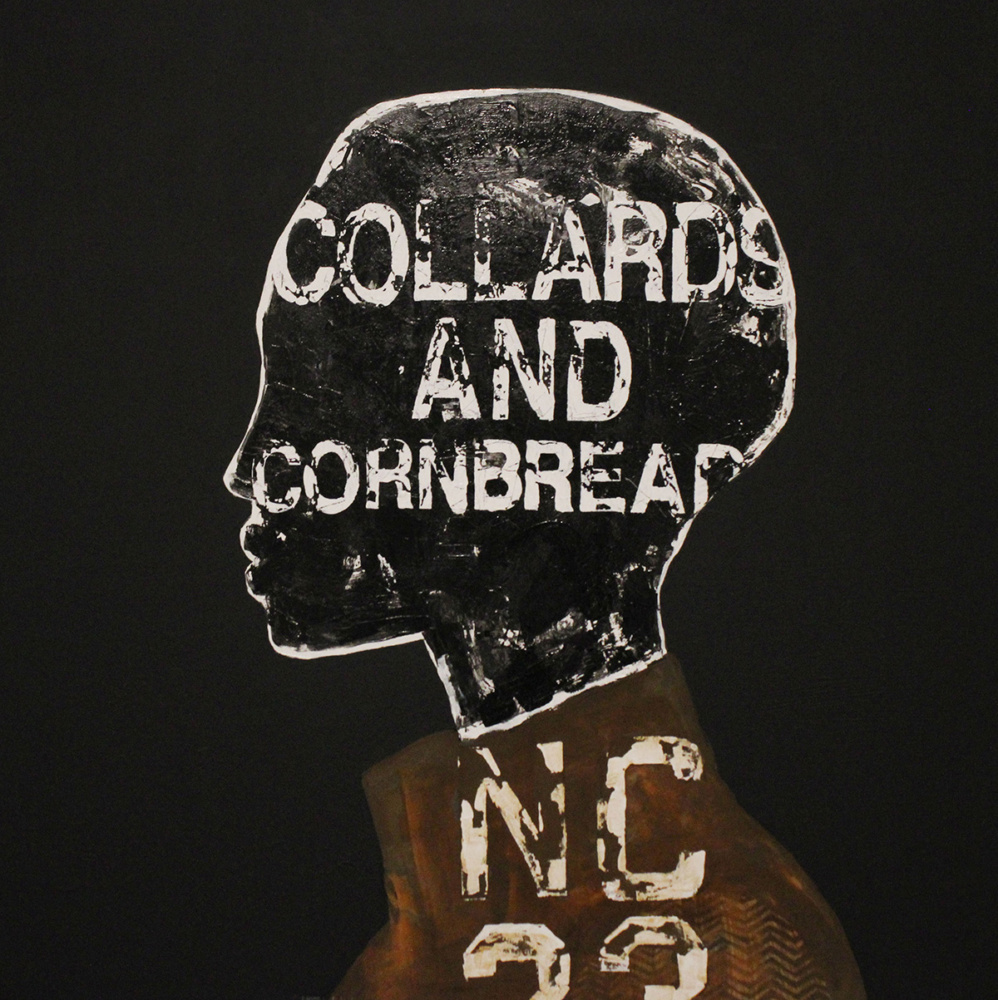

Baskerville’s series of square canvases, filled with expressionless silhouettes, draws on the South’s past as well as his own personal history. In Reimagining Black Wall Street, Durham, NC (2025), a masculine face turns in profile, its dark charcoal color somehow contrasting just enough with the matte black background. The face and broad hat are emblazoned with faded text reading “Black Wall Street—Durham, NC,” a direct reference to the historical street where Ella West Gallery sits. Each canvas echoes this one: blank faces covered with short, evocative statements, typically place names and nods towards Black heritage throughout the South. In their graphic, structural simplicity, they resemble fashion labels, album covers, or tattered posters.

While Baskerville’s works are compositionally straightforward, getting up close, you can see that their monochrome surfaces are actually made from thick paint deliberately scratched and textured. Creole Soul (2025) most directly evokes a patina of time and a sense of place, with all the detailing, from the text and hat ribbon to the cloak around the body, is rendered in shades of reddish brown—at once rust-like and fertile, swampy, earthy. A figure with long dreadlocks, hair seemingly imbued with movement, turns to the side, wearing a broad-brimmed hat and loose, stitched garment. The locks themselves have faded, muddy splotches, as if corroding the picture.

Dallas-based fiber artist Sam Lao presents a row of abstract pieces made with precise rug-tufting techniques, creating a dopamine-inducing effect somewhere between the deliberate artificiality of astroturf and the nostalgic, fuzzy vibrance of a childhood carpet. She invites the viewer to touch these forms, returning to the soft, whimsical feeling of a collective childhood, half-imagined.

Rapids Over Roses (2024) is like punctuation come undone, an ersatz ampersand doing acrobatics. Each curlicue is a different brightly hued pattern, from a blobby blue aquatic center to black-and-white stripes, pink-and-yellow polka dots, and two shades of green swirls along the sides. Rapids and all the pieces are standalone and unframed, vivid against the white walls. Smaller works like Wegg-Lavender (2025) feel like circles lassoed into amorphous shapes, straining against vividly hued bindings. They’re at once futuristic and nostalgic, evoking the pop aesthetic of the 1980s yet reconfigured with a playful, contemporary feel.

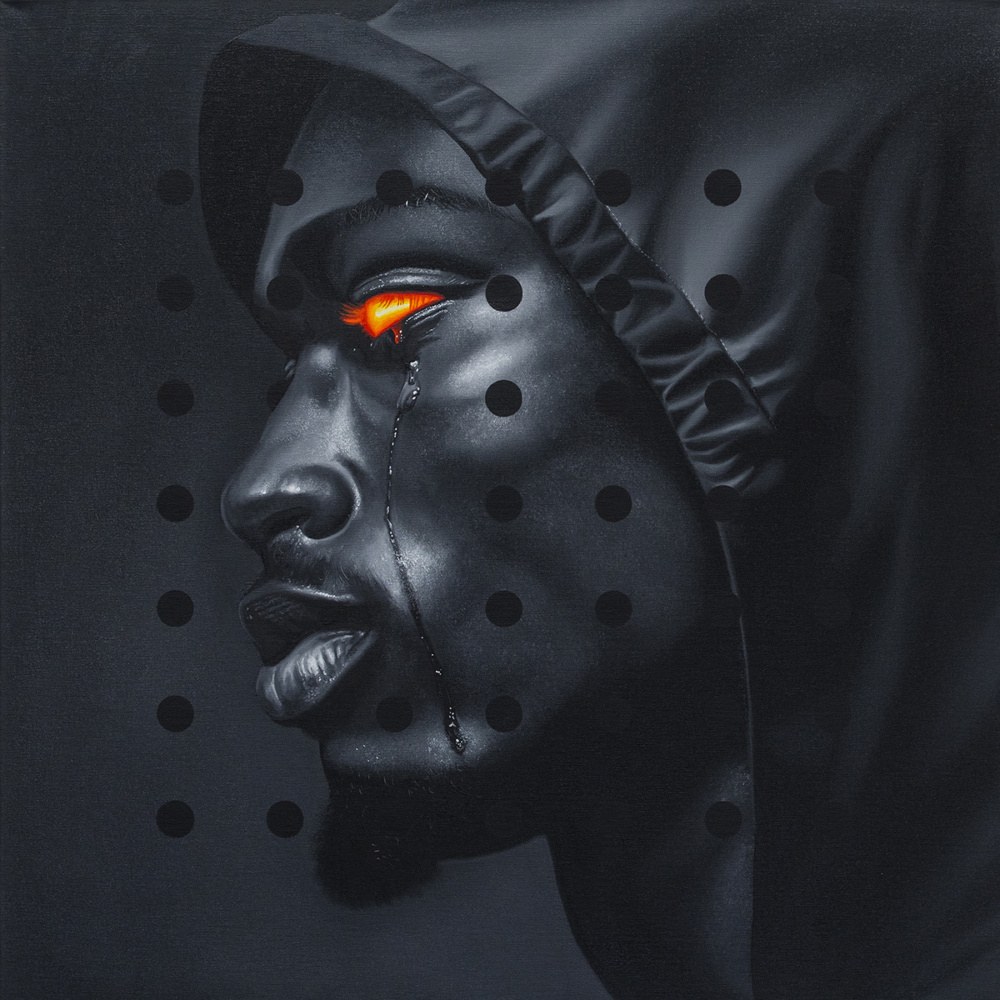

Finally, there is painter Jeremy Biggers, also from Dallas (he and Lao are married), with five canvases that hang alongside the exhibition’s introductory quote. All hail from his Combustible series, which ruminates on the James Baldwin quote, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage, almost all of the time–and in one’s work.”

These square paintings depict black men in luminous grayscale, with a smooth, almost hyperrealistic style. Rage is represented with patches of glowing fire, as if simmering from within: these sparking embers are the only points of color in his works. Combustible 016 (2025) features a face in profile, head half-covered in a silken hood. Only his eye, gazing outward, burns with brilliant yellows and reds that illuminate long, expressive eyelashes. A heavy streak of tears runs down the length of the face, translucent.

While the Combustible paintings may examine a dark past and its echoes today, Biggers’s Defiant series embraces the unapologetic authenticity of contemporary blackness. In Defiant 022 (Jennifer) (2024), an older woman stands fierce and vital, hand cocked on her hip, against a cream background. Her metallic blue shirtdress and silver boots seem to glisten, unexpected red light bouncing off their reflective surfaces. Defiant 017 (Meka) (2024)—one of several circular canvases—features a bearded man in a red beret closing his eyes, as if caught in contemplation or an introspective moment. All of Biggers’s works in the exhibition feature his signature overlay: a grid of polka dots covering parts of each canvas. The artist associates these dots with his mother, via the spotted ladybugs that visited him following her death. They add a sense of structure and freshness to each canvas, as well as another layer of emotional resonance.

The works collected in Southern Grammar are both literally and figuratively centered. Their circular or square canvases and loop-de-loops of yarn are balanced, with few if any off-center figures. More than this, the three artists place Southern black identity, expression, and experience in the very center of their work. If the South has something to say—and Ella West Gallery has made a persuasive argument that it does—listening to the artists in Southern Grammar is a good start.