“The Crossroads of Memory: Carroll Cloar and the American South,” on view at the Arkansas Arts Center through June 1, is the largest ever compilation of Arkansas-born Carroll Cloar’s oeuvre and its most prolific study in over 20 years. [An exhibition of Cloar’s lithographs is on view at the Georgia Museum of Art in Athens, May 17-Aug. 31.] Said to have “purposefully forged a distinct course against Abstract Expressionism,” Cloar knew exactly what he was doing when, in 1954, he decidedly pursued genre scenes of his beloved Delta youth over the trendy abstractions of his contemporaries. His paintings include children and adults; rural highways and urban streets; crowds and loners; rich and poor; and young and old that are as likely to grace the pages of a William Faulkner novel as Cloar’s signature Masonite painting surface. A curator could easily handpick works for an entire exhibition based on any one of these subjects or juxtapositions.

One of the foremost themes in “The Crossroads of Memory” is Cloar’s treatment of girls and women. Sometimes he portrays them as traditional homemakers, as in Goodbye, I Hate to Leave You (1955), in which a woman gazes from the confines of her front porch at a lover presumably leaving for World War I, or in WPA Quilters (1971), which depicts women working in a sewing room during the Great Depression. Other times, he portrays them as social equals to men, as in Day Remembered (1955), a painting of Cloar’s older sister Rhoda and a coed group of friends, or as deeply cherished companions like those in Lovers in a Dry Month (1957), speculated to represent the artist and his wife nestled within the niche of a shadowy landscape. It’s difficult, therefore, to compartmentalize his depictions of women and girls into one hard-and-fast category.

Where women and girls tend to stand apart from Cloar’s other subjects is through his exploration of the Magic Realism movement, said to have greatly influenced the artist, and his expression of Southern folklore. “Blending the everyday world with elements of fantasy,” Magic Realism explains, in part, the eerie, dreamlike quality of many of Cloar’s works. Realism alone is subject to regional dialect, as it carries a different meaning for each culture it represents and each artist it inspires; Magic Realism, however, is like Realism multiplied—layers upon layers of an artist’s memories, each believable in its own right, but otherworldly when combined.

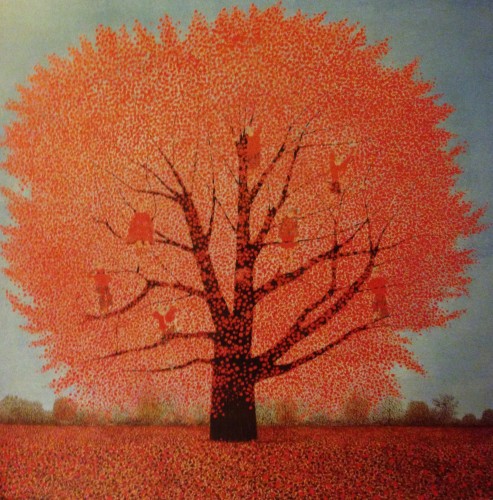

Moonstricken Girls (1968), for example, brandishes an intense yellow-gold moon, which casts an unnatural purple haze over a rural field and a pair of girls who hysterically grasp the temples of their foreheads. Based on an oral legend that associates madness with the cycles of the moon, each element of the painting is realistic on its own, but together produces a composition straight from Cloar’s inexhaustible imagination. Similarly, in The Girl Tree (1964), Cloar draws upon a local story of a tree “only climbed by girls. No boy would get near it.” Little girls hang like blooms from giant limbs the same fairytale way babies pop up out of the ground in the Cabbage Patch.

We see Magic Realism arguably at its best in Halloween (1960). The muse is far less light-hearted than usual, this time, inspired by the Ku Klux Klan. A masked girl dances with abandon, her feet barely touching the ground, and she is just a pair of wings short of flying off into the ghoulish night. She is unaware of the hooded figures along the horizon. Cloar is strategic in placing a girl, rather than a boy, in the foreground, explaining, “I thought the juxtaposition of the symbols of innocence—the little girl, and evil was very interesting.”* In these examples of Magic Realism, Cloar’s female subjects possess supernatural attributes that open the door to a world of freedom beyond playing under the moon, climbing a tree, or trick-or-treating. Here, Cloar’s representations of Southern folklore operate as a symbolic elevation of women’s status beyond what was possible for them at that time in history.

Evidence of Cloar’s heroines can still be found in the South’s visual culture today. Emily Wood, a Little Rock-based artist, seeks to capture quintessentially Southern moments lived by her closest friends and family members. Sometimes working from photographs, other times from memory, Wood admits to “choosing subjects that are particularly related to Southern tradition and uniquely rural.” Placing her faith in the process of painting as much as, if not more than, the finished product, Wood’s images are honest. “I grew up in a small town where everyone hunted and fished—even girls—and got out of school for ‘deer days,’” says the artist. Shootin’ in Church Clothes (2012) features the artist’s young cousin Caroline sitting in a red plastic folding chair and wearing a blue dress and matching hair bow. Set against a picket fence and patch of green grass, her tiny hands masterfully aim a black shotgun into the distance. Fortunately, women and girls aren’t held back by the same restrictions as in the 1960s, but there are some images today that surprise even the most progressive viewer.

Photographer Margaret LeJeune, assistant professor of photography at Bradley University in Peoria, Illinois, created her Modern Day Diana series, named for the Roman goddess of the hunt, to explore the modern notions of women hunters and the issues of gender, power, and representation. While not every photograph features a Southerner, LeJeune first became fascinated with female hunters while living in Arkansas in 2008. In Allyn (2008), LeJeune shows a young woman accompanied by a vase of flowers and homemade cookies, as well as a shotgun and the mounted heads of a deer and a boar. Perhaps Allyn’s goddess status was earned by conquering both the domestic and secular realms.

Wood and LeJeune’s works don’t really fall into the Magic Realism category, but they do fall in line with a longstanding Southern tradition and lifestyle beloved by Cloar. The mythological nature of our folklore lends itself to creative interpretation, and our folklore is rendered most lifelike when we see its goddesses of the South come to life in Cloar’s paintings. Cloar’s version of Realism stakes its distinctiveness in memory; without the context of memory, the paintings lose their multidimensional quality that makes Cloar so special and establishes a playground for the liberated female spirit.

*The centennial of Cloar’s birth in 2013 prompted a catalogue authored by exhibition curator Stanton Thomas, the largest collection of Cloar color reproductions. Direct quotations from and about Cloar came from this publication. More information about The Crossroads of Memory can be found at www.arkansasartscenter.org.

Emily Wood will be featured in an exhibition at Justus Fine Art in Hot Springs, Arkansas, June 4-28, 2014.