A trove of works from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, established by Atlanta collector William S. Arnett in 2010, has been given to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

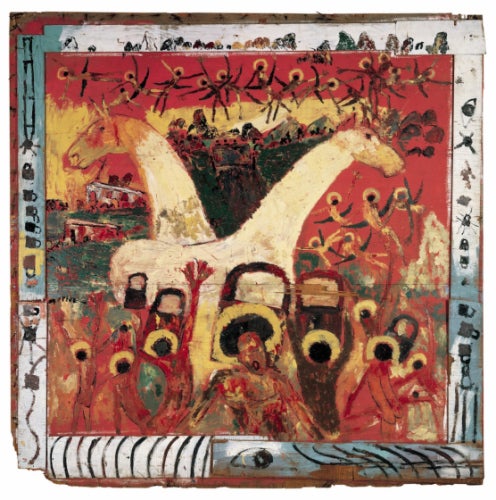

The gift comprises 57 works by African-American artists from the South, including 10 pieces by Thornton Dial and 20 Gee’s Bend quilts, along with works by Lonnie Holley, Purvis Young, Nellie Mae Rowe, Mose Tolliver, Joe Minter, Ronald Lockett and others. The selections were made largely by Sheena Wagstaff and Marla Prather, the chair and curator, respectively, of the Met’s modern and contemporary department.

The donation will give the museum its first Gee’s Bend quilts, which have received popular and critical acclaim since a major touring exhibition in 2002, and have been compared to modernist works by canonical artists.

The foundation’s gift to the Met, an encyclopedic museum with 6.2 million visitors per year (compared to the High’s 400,000), will arguably do more to promote the work of Southern artists than it would have at a museum such as the High, where it likely would’ve joined the folk art collection—which has a dedicated, but vacant, curatorial position that was recently endowed with a $2.5 million gift. The works also might’ve fallen victim to a common problem of regional museums that attempt to strike a balance between embracing their local artists and not appearing provincial.

Arnett is a staunch defender of the artists and art he acquires, taking exception to their being labeled “Outsider” or “folk” simply because they are not white and educated. He says, “It’s art,” no modifier needed.

In the Met’s press statement, Arnett says: “This collection documents a little-known tradition that began in the Deep South, likely during the earliest days of slavery. It evolved and appeared in the open when the Civil Rights Movement empowered these African American artists to let their previously hidden visual arts come out of the woods and cemeteries and be seen in the front yards and along the roads. Art lovers and cultural historians everywhere owe a great debt to the Metropolitan, where this historic work will now be seen alongside the current and past art of the world’s great civilizations.”

Met director Thomas Campbell calls the gift “a significant enlargement of the museum’s holdings of work by black American artists. It embodies the profoundly deep and textured expression of the African-American experience during a complex time in this country’s history and a landmark moment in the evolution of the Met.”

Some observers had expected Arnett to donate most of the foundation’s works to the High Museum, despite some widely known friction between the two. For example, the 1996 Souls Grown Deep exhibition that was held at City Hall East during the Olympic Games was originally planned for the High, which had recently created a curatorial position for folk art. Arnett emphasizes that “the gift has nothing to do with the High, and trying to relate the two does a disservice” to both institutions. Arnett says he has no issues with the museum: “Over the years, thousands of pieces from my collections have been shown in the halls of the High. I have been a supporter of the museum for 50 years and will continue to work with them in whatever capacity they wish.”

Of course, the well runs deep. The stockpile of works in the foundation’s massive warehouse means there is still plenty to go around, and Arnett hasn’t ruled out the possibility of giving more works to the High, emphasizing the foundation’s willingness to work with interested parties [including my husband, Carl Rojas, and I, who mounted a Lonnie Holley exhibition at Ponce City Market with works from the foundation in April 2014]. In fact, it was the Met that approached Arnett about the gift. “The High never asked,” he says.

Arnett is pleased that “the Met is committed to seeing this work enter into the contemporary art dialogue where it belongs.” An exhibition of works from the Souls Grown Deep gift, organized by modern and contemporary curator Marla Prather, will be held at the New York museum in the fall of 2016.

paint on wood on wood, 84 by 84 inches.

96½ by 37 by 29 inches.

and marker on paper.

50 by 53 inches.