Camille Farrah Lenain is a French-Algerian documentary photographer and filmmaker living and working in New Orleans. Les Soeurs de la Chasse / Sisters of the Hunt culminates five years of Lenain’s work photographing and interviewing women who hunt in rural France and Louisiana. A multimedia exhibition gathers a film and sound installation alongside photographic portraits of the huntresses and the land.

The gaze of a young huntress meets the eye of the viewer entering the gallery. Her lashes shadow half of her blue, grey irises, a shotgun slung over her narrow shoulder. Her hair tied back, chapped berry lips set. Small flecks of blood spatter across her white cotton tank top. The wood grain and black steel of the gun in her arm lend her stare their threat of life or death. The women on the walls often gaze back like this, like killers. I am not used to the deadly gaze of a woman.

In another photo two sisters embraced, the taller behind the shorter, hands and arms entwined, a bleeding hangnail, a ring, one in camo, the other in fleece. Kin of the sisters at the opening pointed to the image, explaining to friends, “It’s on the little house on the pond. See the red door?” Lenain paired the portrait of the two sisters with a photo of an azalea ablaze with pink flowers shot through a stand of trees, a diptych of the huntresses and their line of sight.

“What is all this red?” a woman asked, her finger tracing a curved trail of blood in the gravel of an image. She looked at the title, “Death” and went silent. Lenain paired this photo of a red streak where the huntresses dragged a hog from the road, in a diptych with another landscape of the drape of berries nested in lichen covered branches titled “Growth” .

A deer stand hangs in the bend of an oak branch, and another shotgun is cocked in the crook of an arm, loaded with two gleaming shells. The French huntress Rachel’s pigtail braids rest under her orange cap, a small bronze snipe pinned to the side. Her gold, star-shaped chandelier earrings dangle above a brown quilted vest over a green plaid shirt.

In another photo her hand unfolds the delicate wing of a snipe, its lifeless feet trailing, black beak held high between thumb and forefinger, suspended in front of the blunt fan of a green palm with leaves that echo the wing.

Lenain told me about first meeting Rachel, now a dear friend, in the hunter’s home in Arles. Lenain, who is from Paris, didn’t grow up with guns or hunting. Her interest in gun culture emerged out of exposure and fear. Islamophobia is endemic to both France and the US, and Lenain has a visible tattoo in Arabic on her wrist. In the Acadian setting of the gallery the sound of shooting is commonplace. Lenain was held up at gunpoint in New Orleans. “I needed to understand how they work,” she said. She felt vulnerable in Rachel’s home, surrounded by her hunting rifles. Rachel admitted she also felt vulnerable in the photographer’s gaze. She didn’t know Lenain’s intention for the work, and whether she would present her and her culture as brutish, backward.

Lenain gave up making a metaphor out of the camera as gun, lens as scope, shooting her subjects as they shot their prey. Yet she remains aware of resonances between her and the huntresses’ processes. Four of the photographs on view are digital, the others she shot on medium format film. “When you scan medium format you remove dust for hours,” Lenain said. Sitting in a duck blind or a deer stand for hours, she, too, observed the patience of the hunt, waiting in stillness, in silence, for that quarter of a second that disrupts time, that irrevocable moment of harvest.

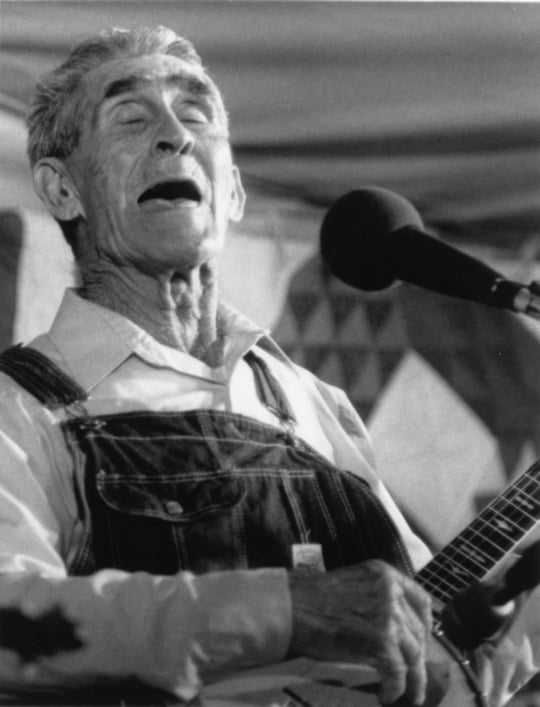

A celebration honored the opening of the exhibit. In the center of all of the carnage on the walls and under the sure, mournful gaze of the huntresses, live Acadian music filled the space followed by couples two-stepping. One couple danced so small, leaning and swaying, their two step a gesture as natural as their embrace.

Lenain calls the women she portraits “huntresses,” in a nod to Monique Wittig’s 1969 novel Les Guérillères, set among a speculative society of revolutionary, queer, feminist militants. Wittig invented a diminutive, feminine form of the French word for warrior for the title, a useful evolution of the language in the gender expansive militancy of post-1968 France. Women hunters are still outsiders in both Louisiana and France.

Over the course of the project Lenain also began studying ancient mythological goddesses of the hunt, from Diana to Artemis, research that developed out of her time with the women waiting in deer stands and duck blinds, as if the goddesses appeared necessarily to the artist on their own.

There seems always to be more to love and to violence than meets the eye. A farmer unearthed a 4,500-year-old statue of Anat, the Canaanite goddess of love and war, from his field in Khan Younis in April of 2022.

Palestinian thinker Abduljawad Omar writes of resistance subjectivity as a melancholic disposition, referencing the work of Lebanese Marxist Hussein Mroue, whose 1982 essay “The Sadness That Kills v. The Sadness of the Fighter” proposes the latter sadness as noble. This most beautiful sadness he writes is as distant from the sadness that defeats the morale of the fighter as the sun setting into the ocean is from the water it only appears to touch.

In a sound installation outside the gallery the women spoke of the thrill of the hunt, but more so of their respect for the animals they harvest and the weight of taking a life. “Everything we kill we eat… it’s something to be grateful about. We don’t take their life just for nothing,” the daughter and mother, Rebecca and Dana said. “I feed my home. And I feed my mother’s home,” Rebecca said. The hunt also sustains the matriarchal lineage for Valerie, a Black Creole woman, and the only Black huntress Lenain photographed. Valerie also has a daughter, and Valerie’s mother was the first person she spoke to when she killed her first deer. “Black and Creole women are in a minority as hunters in the area,” Lenain said. “However, Valerie is exceptional.” The soundscape lives in a little structure lined with palms, bamboo and fairy lights, where interviews with the huntresses are woven through an original score by Lafayette-born musician, Tif “Teddy” Lamson. Here in “The Palmetto Blind” Lenain invites the audience to “come sit and wait the way the huntresses do.” Beside the glowing palms I listened as they discussed their relationship to animals, to guns, to gender, and to the irreversible act of killing.

Behind the installation the constellation Orion beamed over the brown rows of farmland. He’s a hunter, too, and the great love of Artemis, virgin goddess of the hunt in the Greek pantheon. She placed him there in the sky after his tragic death, as a tribute to their blinding if forbidden love.1

Orion reigned before dawn over the prairie winter sky several years ago as my father, brother and I prepared to hunt pheasant. Ice caught like dew on the grasses. My father’s old friend taped one of the lenses of his eyeglasses on the drive. Then came the long walk, slow and ceremonial after dawn. We spread across the tall, skin-brown grass in a four-man front, careful to hold the line. I told Lenain the story of my hunt, of holding a camera rather than a gun, of one wounded bird that got away. My brother Jack missed his shot, so the two of us stayed behind in the field searching for the bird after it fell and hid to heal or to die. Jack told me how the fathers of his suburban friends took him and their teenage sons to the shooting range to fire AR15s for fun, how it felt like being in a video game. Once we were home my dad dressed his own kill. He showed me how he would pluck and gut it by pointing to his wife’s neck and belly, indicating where the cuts would be on her petite frame.

She gave him a hard, quiet look. As a huntress in the “Palmetto Blind” said, “This is how we are built. And this is how they’re built.” I roasted the pheasant with care, with juniper and bay. The bird’s long autonomy felt astonishing, miraculous. Cut down mid flight, this bird died free, I told Lenain.

Near the end of our conversation she said, “I can’t stop thinking about that. ‘This bird died free.’”

- In some versions of the myth he was murdered by Artemis. Less disputed is their hunt together in Crete. She is also the goddess of the moon. Lenain’s photo of the moon over the water at blue hour in Henderson, LA became the backdrop for the bandstand on opening night.

↩︎

Camille Farrah Lenain: Soeurs de la Chasse / Sisters of the Hunt is on view through May 26, 2024 at the NUNU Arts and Culture Collective in Arnaudville, LA. Closing events will take place the weekend of May 17-19.