In concrete stories, artist and filmmaker Sindhu Thirumalaisamy traces the lifecycle of concrete, from quarry to dust. The immersive program included two films portal peephole planet (2025) and dust-time (2025) as well as advanced preview screenings of three films-in-progress titled Crusher (கிணறு ெவட்ட பூதம் கிளம்பிய கைத), a fortess [excerpt], and reclamation. As a cohesive thematic project, concrete stories meditated on concrete’s entanglements with empire, modernity, and industrialization within the geographic context of urban wetlands, a topic Thirumalaisamy has explored since 2017.

Organized by Salome Kokoladze, curator at Aurora Picture Show—one of the few Houston-based cinema and media arts non-profits committed to presenting experimental and independent films—concrete stories was presented October 10 with interstitial poetry readings by multimedia artist, activist, and educator Ahimsa Timoteo Bodhrán. Its presentation also incorporated improvised sound mixing during the films portal peephole planet and reclamation, further activating the “film-performance,” as articulated by Thirumalaisamy.

Liquidity functions as both theme and structure in Timoteo Bodhrán’s lyrical verse, while operating within literal and conceptual registers in Thirumalaisamy’s films. Visual representations of water and earth in motion harmonize with explorations of concrete as a liquid form, elastic in its social and cultural contexts. The co-presence of text, sound, and image amplify resonances between these disciplines in a remarkable manifestation of material poetics. The works translate the tensions and antagonisms inherent to concrete by moving fluidly between form and formlessness; oblique and transparent; abstract and pictorial.

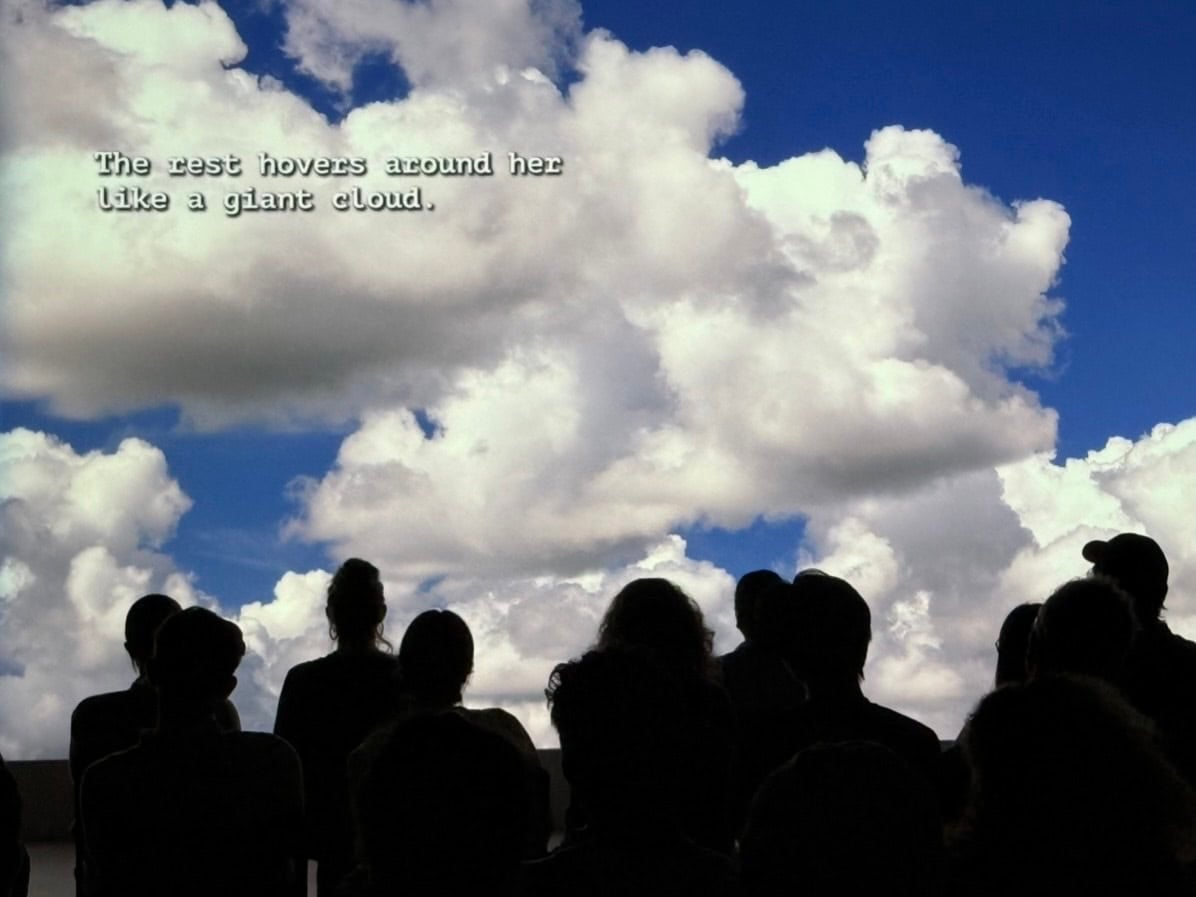

The first film, portal peephole planet, opens with clouds that shimmer and slip rapidly across the frame. The following sequences oscillate between grainy shadows and pure light. Train tracks appear intermittently in the upper register. A small aperture stays in a fixed position, peering into an alternate space. Ambient noise tapped from the venue’s back porch and a nearby cement terminal add not only a localized dimension, but an element of instantaneity. Timoteo Bodhrán recited Amongst the Clouds (2023), a piece reflecting on ecological interconnection, cycles of remembrance, and the transformative potential of all matter. Ecocritical themes of material vitality and returning invite viewers to consider: what is shared between clouds and concrete?

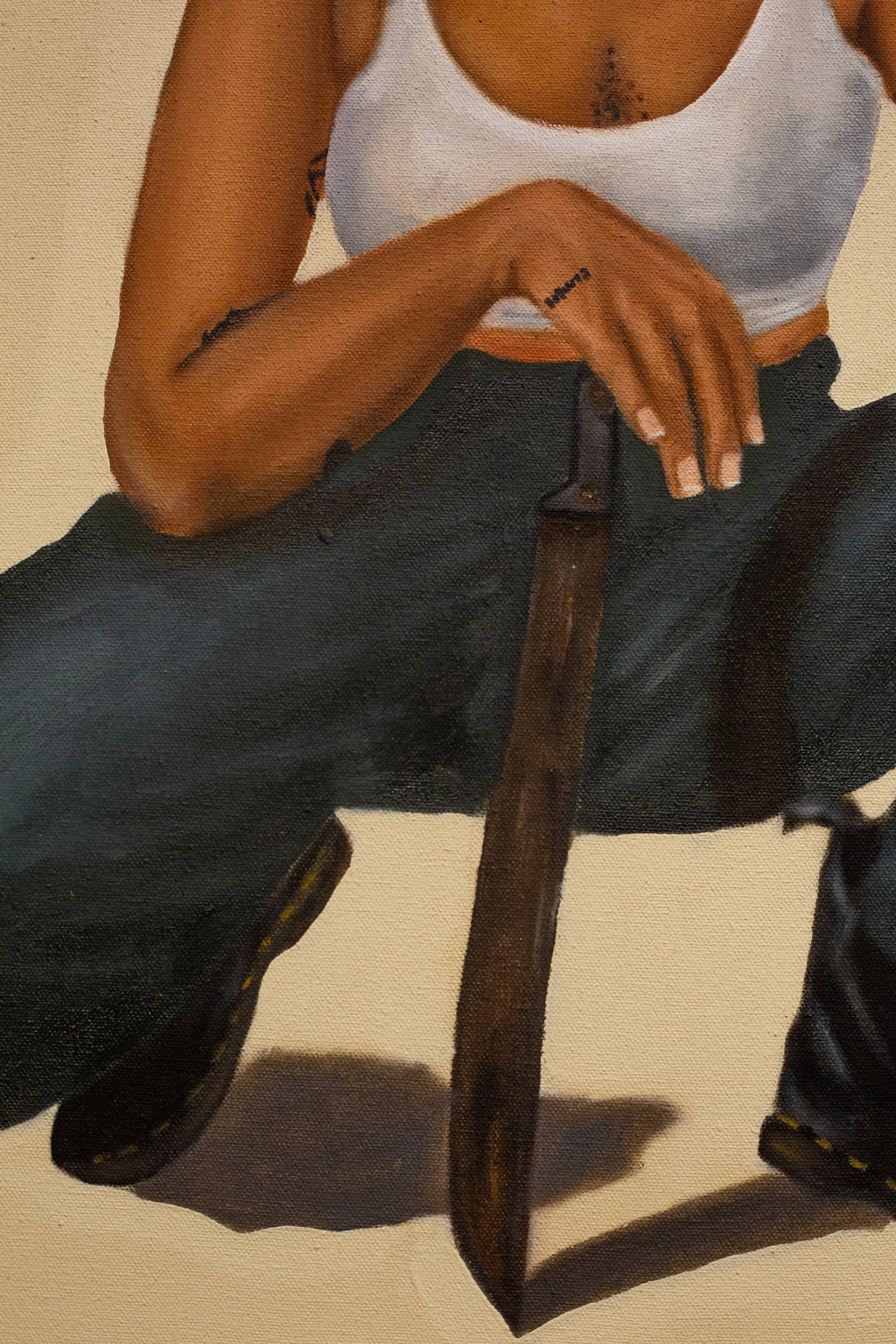

Crusher (கிணறு ெவட்ட பூதம் கிளம்பிய கைத), the following film, illustrates the web of places, procedures, and people that comprise the concrete industry. The viewer is carried through a quarry processing plant in Southern India. The handheld camerawork destabilizes the observer’s perception, frequently shifting and refocusing on the sights and sounds of the plant: fragmented shots of a man guiding Thirumalaisamy through the area, goats seeking shade, mounds of earth, and the network of machinery like excavators, conveyor belts, and crushers that break-down and refine aggregates.

The Spanish Coquina Quarries in St. Augustine, Florida, is the subject of the third of Thirumalaisamy’s films, titled a fortress [excerpt]. Under Spanish rule in the seventeenth century, enslaved laborers constructed the Castillo De San Marcos and much of St. Augustine’s civic architecture with coquina, a native limestone consisting of mollusk shells and sand. This film brings into clearer focus concrete’s relationship with modern architecture and its alienation of spatial relations. One poignant scene flashes a fossil-like impression of a cannonball in the fortress wall, a tangible representation of the colonial violence enacted at the site and constituted within the material. Thirumalaisamy and Timoteo Bodhrán explore the profound ways that architecture can reorder existing Indigenous practices and relationships to land and water. In the context of colonial architecture, concrete has historically been utilized as an instrument of ideological amnesia, the forced erasure of history and memory. Timoteo Bodhrán’s reading of Archipelago (or, What I think when I say Bronx) (2012) embroiders the film with the memory of ancestral homelands, Indigenous knowledgescapes, and their violent occupation:

This earth. This small place we gather against. Would I

take you into the woods? Show stone? Show the places we

gather? The place of calm waters, no ships? The places our songs

come from? The place inside. Inside, besides the brambles,

bricks, past the stickers and thorns, porn parlors. The place my

mother hacked to. The place I am still going. This never

forgetting.1

Thirumalaisamy’s sensorial filmmaking engages the notion of haptic aurality, which conceives of sound as tactile.2 This framework considers how multisensory transmission and perception create an embodied experience of cinema. Thirumalaisamy furthers Laura U. Marks’ concept of haptic visuality by mediating the haptic through vision and sound. In reclamation, Thirumalaisamy synthesizes the visuals of water flowing over concrete, followed by scenes of shells and rock compressing and churning with live sound arranging. The materiality of concrete’s production is physically manifested through Thirumalaisamy’s sonic ‘mixing’ and ‘aggregation’. Texture also functions to critique cultural associations of concrete: by illustrating sequences of terrestrial processes, Thirumalaisamy re-textures concrete’s claim to ahistorical objectivity and impermeability as a ‘blank’ modern material, demonstrating its subjectivities and its flow through time.

Dust-time is a two-channel film that presents the dialectic of universalism and particularity of concrete within urban infrastructures. The left frame shows a continuous shot from the inside of a moving car. The lens focuses on the accumulating dust glued to the window while the blurred contours of a highway overpass float by. On the right, we observe the quiet commemoration of funeral rituals. Grief takes shape in the river’s ancient current; in the marking of ash to skin; in the patina of dust. A voice asks,“What kind of soil does a highway make?” Does concrete return to dust, like we all do? Thirumalaisamy locates the personal within the ubiquitous substance of concrete. The sacred and mundane co-exist, side by side. To echo Adrian Forty, a dance between memory and oblivion.3

1. Ahimsa Timoteo Bodhrán, Archipiélagos (Memphis, Tennessee: Walls Divide Press, 2019).

2. Haptic aurality furthers the concepts of haptic visuality and haptic hearing introduced by Laura Marks. See Laura U. Marks, The Skin of the Film Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham: Duke Univ. Press, 2007).

3. Adrian Forty, “Concrete and Memory” in Urban Memory: History and Amnesia in the Modern City, 75-98, 2005.