Exactly fourteen days after Sable Elyse Smith’s exhibition “BOLO: be on (the) lookout” opened at the Lower East Side gallery JTT, Jemel Roberson was fatally shot by police after heroically apprehending a gunman at a Chicago bar. Roberson, who was a Black legally armed security guard on duty and who aspired to one day become a police officer himself, was assumed to be the gunman the shooting officer was told to BOLO (police code for vigilance when a violent criminal is at-large) for and was swiftly put to death. Smith’s exhibition, which gets its title from this same acronym, explores the racialized criminal justice system and the unnatural aesthetic structures used to indoctrinate communities with the ideology of “the system” from childhood.

Childhood has proven to be a fertile, if incredibly fraught, frame of reference for Smith, whose video How We Tell Stories to Children was on view at Atlanta Contemporary earlier this year. Smith, who attended high school and college in Atlanta, has spent most of her life—nineteen years—with her own father imprisoned. Amid intercut footage of city streets and a young man running in slow motion, How We Tell Stories to Children shows part of a recorded conversation between the artist and her father, who speaks to her from his cell while he listens to Alicia Keys’s 2001 song “Troubles.”

In “BOLO,” a large installation with a stage-like floor of drab linoleum tiles and a grid of monitors immediately grabs your attention, refusing to stop its incessantly looping, manic sound in the gallery. Depicted in the repeating eight-second clip playing on the screens is the classically naive and docile white actress Julie Hagerty, ironically pretending to audition for Spike Lee’s 1995 adaptation of Richard Price’s crime novel Clockers. After coyly asking, “Did I ever tell you the first time I killed somebody?” with the intonation of a Brady Bunch cast member, she sighs and the audience erupts in laughter at the idea.

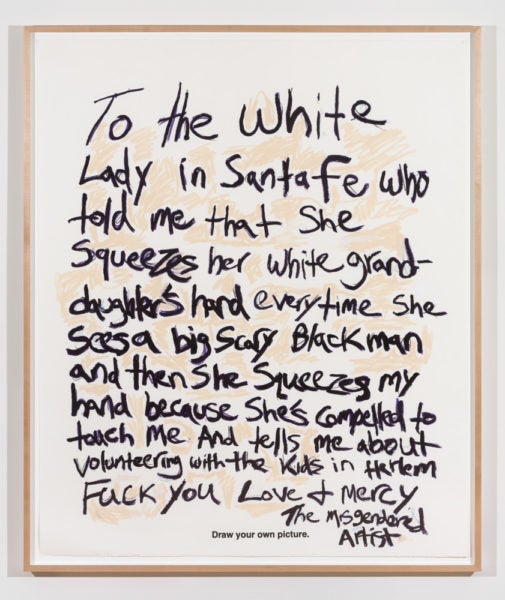

The comedic incomprehensibility of Hagerty’s violence and the obvious assumption of Roberson’s speaks to the ingrained racial attitudes that pervade not only the justice system but also the elite, predominantly liberal entertainment industry. That the sort of violence of off-colored jokes could hurt as deeply as a violent assault is made evidently clear through another work in the exhibition, Coloring Book 21 (2018), which recounts—presumably—one of the artist’s experiences in the art world: “To the White Lady in Santa Fe who told me that she Squeezes her white grand-daughter’s hand everytime she sees a big scary Blackman and then She Squeezes my hand because she’s compelled to touch me and tells me about volunteering with the kids in Harlem Fuck You. Love + Mercy – The Misgendered Artist.”

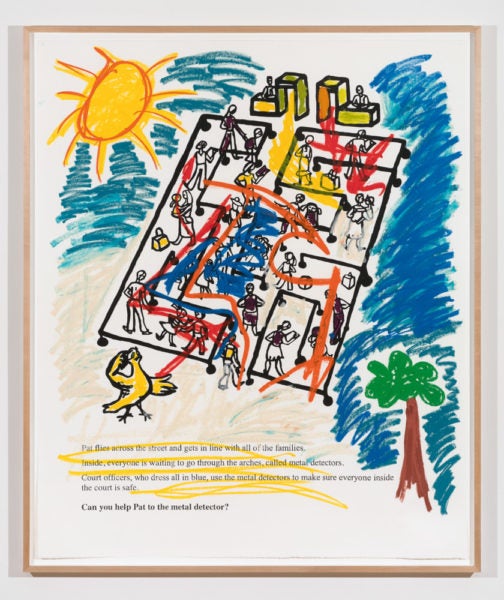

Coloring Book 21 comes from a body of work Smith has been creating since 2017 in which she exuberantly marks enlarged, reproduced coloring book pages. Though seemingly commonplace at first glance, the illustrations and prompts in the pages reveal that the book is a tool to expose children to the experience of court in order to neuter the tense, traumatic experiences and life-changing outcomes it often supplies. The dark surrealism of a child being prompted to help an animated bird navigate a maze to “get to the metal detector” in one page is not lost on Smith, who sketches a childlike, sunny landscape in the background of this suspended labyrinth. In another two works from the suite, Smith frenetically scribbles over the outline of a white woman the book names “Judge Friendly.” The scribbles build throughout the series to the moment when—absent of outlines, with the simple prompt “Draw Your Own Picture”— Smith confronts her own trauma with the racist white lady in Santa Fe.

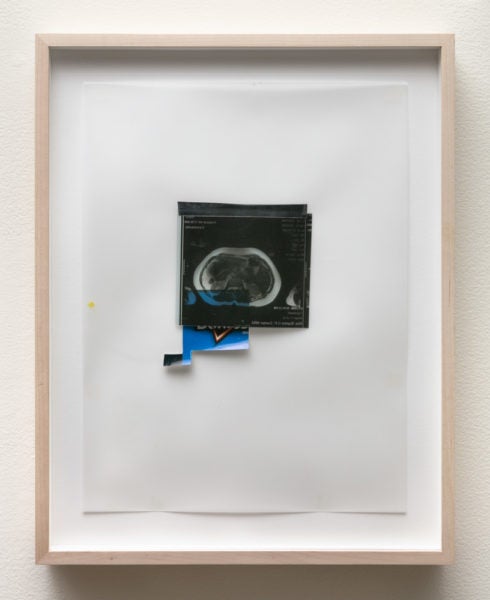

Tucked in the corner next to the blaring video monitors, the most unsettling work in the exhibition is the collage maps for a body thirsty for some other shit (2018), which is comprised of a small, tenderly cut Doritos bag and an MRI of a person’s interior mounted to a wrinkled sheet of translucent vellum. The harrowing title, combined with the sparseness of the collage and the unholiness of a chip bag pressing itself against a picture of the inside of a person, evokes the simultaneous banality of waiting (in court, in prison, in school) and attempting to judge a person’s intentions in a moment of conflict. There is also an impossibly tender, small yellow paint stain in the corner of the work that feels expertly perverse, if maybe accidental. If Smith’s Coloring Book works are visually and materially reminiscent of Glenn Ligon’s series of the same name, the sparse collage works like maps for a body… demonstrate an exciting new territory for Smith.

Sable Elyse Smith’s solo exhibition BOLO: be on (the) lookout is on view at JTT in New York through December 16.