In 2015, the exhibition Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933-1957 brought the experimental Southern art school back into conversations about the histories and legacies of American modernism. After all, contemporary tendencies to blend of high and low aesthetics, combine various mediums, and blur of the boundaries between art and design all reflect the values of Black Mountain College and the Bauhaus refugees who made the North Carolina institution their home after the forced closure of the legendary German art school in 1933.

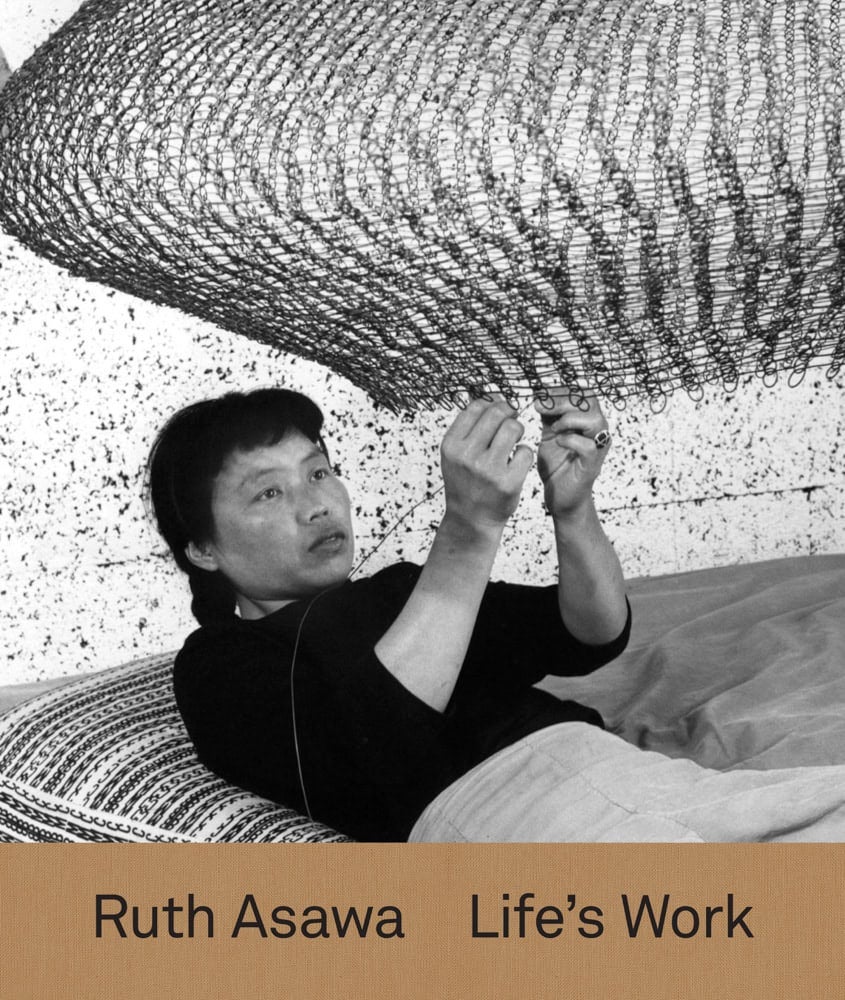

The latest evidence of Black Mountain’s resurgent influence came on May 1 when sculptor and Black Mountain College alumna Ruth Assawa was celebrated in a Google Doodle marking the first day of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month. This tribute closely followed the April release of the catalogue accompanying the Pulitzer Art Foundation’s 2018 exhibition Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work. The catalogue offers an expansive exploration of Asawa’s career, riddled with revelations about the artist’s love of materials, her passion for arts education in San Francisco, and the delicate balance between formal experimentation and expressions of identity that are the hallmarks of Asawa’s too-long-underappreciated contributions to American sculpture.

Curator Tamara H. Schenkenberg opens the catalogue with a thorough overview of Asawa’s life and career. Born into a Japanese immigrant farming family in Southern California in 1926, Asawa and her family were prisoners in an internment camp between 1942 and 1945. During her time at Black Mountain College from 1946 through 1949, Asawa was encouraged to take an interdisciplinary approach to her art, having been primarily interested in drawing and painting when she started at the school. According to Schenkenberg, Asawa said that the faculty at Black Mountain “taught me that there is no separation between studying, performing the daily chores of living, and creating one’s own work…Through them I came to understand the total commitment required to be an artist.”

Asawa’s teachers at Black Mountain included Jacob Lawrence, John Cage, Willem de Kooning, and Buckminster Fuller. Asawa remarked that her dance courses with Merce Cunningham were especially inspirational, and you can see how the seeming randomness of Cunningham’s chance-driven choreography may have influenced the organic, curving lines we most associate with Asawa’s work.

Asawa’s primary teacher at Black Mountain was Josef Albers, whose Basic Color and Design class opened “another world” for her. Albers’s groundbreaking theories about color inspired Asawa, but it was his approach to artistic materials that would lead to the artist to find her craft as a sculptor. Black Mountain College students weren’t required to attend classes, but they were expected to pitch in on chores at the isolated, rural school, including everything from tending gardens to maintaining buildings. Asawa was familiar with repetitive, physically intensive labor from her childhood spent on farms. (“Doing is living,” the artist once said. “That is all that matters.”) In this unique pedagogical environment, Asawa and her peers were encouraged to consider the creative use of commonplace materials such as eggshells and leaves. It was while attending Black Mountain that Asawa visited Mexico and discovered the wire egg baskets that inflamed her imagination. In keeping with Black Mountain’s process-based, hands-on approach, Asawa found local Mexican artisans who taught her the wire-looping techniques—essentially knitting with pliers—that became her primary mode of expression for decades.

The catalogue for Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work also contains astute essays by curator Helen Molesworth and critic Aruna D’Souza about Asawa’s cohabitation of roles as an artist, mother, and wife and how the concept to transparency—visual and otherwise —is explored in the artist’s iconic forms. (Molesworth previously curated Leap Before You Look, the 2015 Black Mountain College survey that is attributed with sparking a new wave of interest in the school.) These essays are neatly presented at the beginning of the catalogue, followed by around seventy pages of images of Asawa’s works. A final section provides a visual timeline illustrating the evolution of the sculptor’s forms over the course of her career. This relatively strict separation of words and images is especially effective here and seems almost necessary when presenting art like Asawa’s. The artist’s sculptures radiate such quiet stillness and grace that it would be distracting to have dense text crowded against images of Asawa’s meditative and mysterious forms.

Edited by Tamara H. Schenkenberg and featuring essays by Helen Molesworth and Aruna D’Souza, Ruth Asawa: Life’s Work is out now from Yale University Press.