Fashion, photography, history, and social commentary come together in Omar Victor Diop’s show “Project Diaspora,” on view at Atlanta’s SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film through August 20. “Project Diaspora” stitches together the artist’s journey to discover his African heritage and the impact of trade, diplomacy, and slavery on our view of Africa. In the 18 large-scale photos on display, Diop recreates art historical portraits of famous people of African descent as they would have been presented by European artists from the 15th to the 19th centuries. The works are more than historical studies, however, as Diop inserts such elements as vivid fabrics from his native Senegal and designer futbol gear; these elements connect the works to the present day and speak to our current notions of “world culture.” Diop wears many hats (and not just of the fancy feathered variety seen in his work Albert Badin) as he works simultaneously as photographer, model, editor, costume designer, and stylist to create these works.

Diop was born in Dakar, Senegal, in 1980, and has only been taking photographs since 2011. He previously was a corporate worker bee specializing in communications, and in 2012 left the corporate world to follow his artistic aspirations. Diop, who still lives in Dakar, now uses his camera to “write” the stories he wants to tell about his subjects. In his studio, he stages elaborate portrait sessions with eye-catching backgrounds and quirky props. The lush tones and art historical references will remind viewers of Kehinde Wiley’s grand paintings, and the clever photographic semiotics evoke the work of Cindy Sherman.

The Sherman reference is especially apt for “Project Diaspora” because all of the images are self-portraits. The sources of these works include paintings, sculptures, and photographs; some are by notable artists like Diego Velázquez, and some are engravings in books by unknown artists. Diop chose portraits of military leaders, artists, writers, and even Frederick Douglass. He seems interested in transporting these historical subjects to our modern day as a way of paying homage to their (often forgotten) legacies. The artist’s self-conscious act of styling reminds viewers how the original sitters may not have had agency in their portraits.

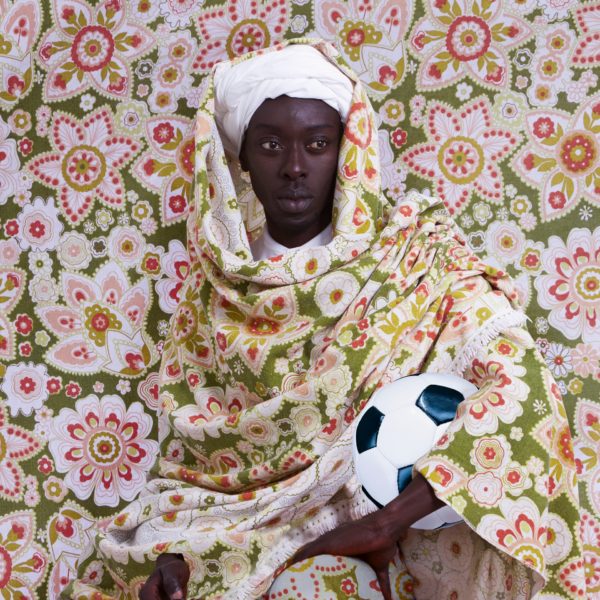

For A Moroccan Man, Diop recreates the portrait of an unknown man painted by José Tapiró y Baró. In the original image, the sitter is framed by elaborate folds of fabric that create a billowing headdress and robe. Diop’s version uses an elaborately patterned fabric from Senegal, with a vibrant flower motif in green, pink, and white. In Diop’s version, the artist holds a soccer ball, which breaks up the flowing fabric. The portrait of Frederick Douglass takes the stern-looking man and transforms him into a dandy by the simple measure of adding a color vest, tie, and backdrop. Diop’s sporty prop in this piece is a whistle.

In Juan de Pareja, Diop perfectly recaptures the mood of the original portrait by Velázquez. The rich tones of green in Diop’s photo appear both painterly and brooding. A lace collar and elaborately pinned and buttoned fabrics evoke the original time period of the Velasquez piece, except for the pair of soccer shoes that Diop cradles.

Most of the portraits that Diop draws from are from a time before organized soccer took off in the early 1800s, but those anachronistic details add another layer of depth to the work. All of the sports memorabilia speaks, to some degree, to traditional ideas of masculinity. They certainly also allude to stereotypical representations of black males in popular culture. The soccer props also serve to create bridges between cultures. Imagine these portraits hanging on the wall of a Peruvian, Swiss, or South African museum—soccer is the common language between these cultures.

For Diop, photography serves as a language to tell stories of past and present, and a tool to examine history’s representation of blackness through visual media. The tradition of West African studio photography is carried through in his work, and traces of Seydou Keïta and Malick Sidibé are evident. The proud postures and opulent backgrounds of these works speak to liberation from colonial oppression, and give Diop’s source subjects a fresh voice in our contemporary and still divided world.