Sometime in my freshmen year of college, I checked out the journal of an artist who I had recently encountered in a survey art history course. White blocky letters on the book’s thin spine spelled its title, Pontormo’s Diary, and its rusty orange cover conjured dated, institutional blandness. I was a disappointed if a little intrigued by the mundane record-keeping inside—mostly, lists of meals and subsequent maladies. Where was the poetry of ethereally voluptuous pictures of floating drapery and strange-bodied people?

Though I remembered the book because of its unexpectedly boring detail, I never considered the unseen labor of the person who translated the Italian into English, a Brooklyn-born woman named Rosemary Mayer [1943-2014]. Her own work was the subject of the recent exhibition “Rosemary Mayer: Beware Of All Definitions,” curated by Katie Geha and Marie Warsh for the UGA Lamar Dodd School of Art Galleries.

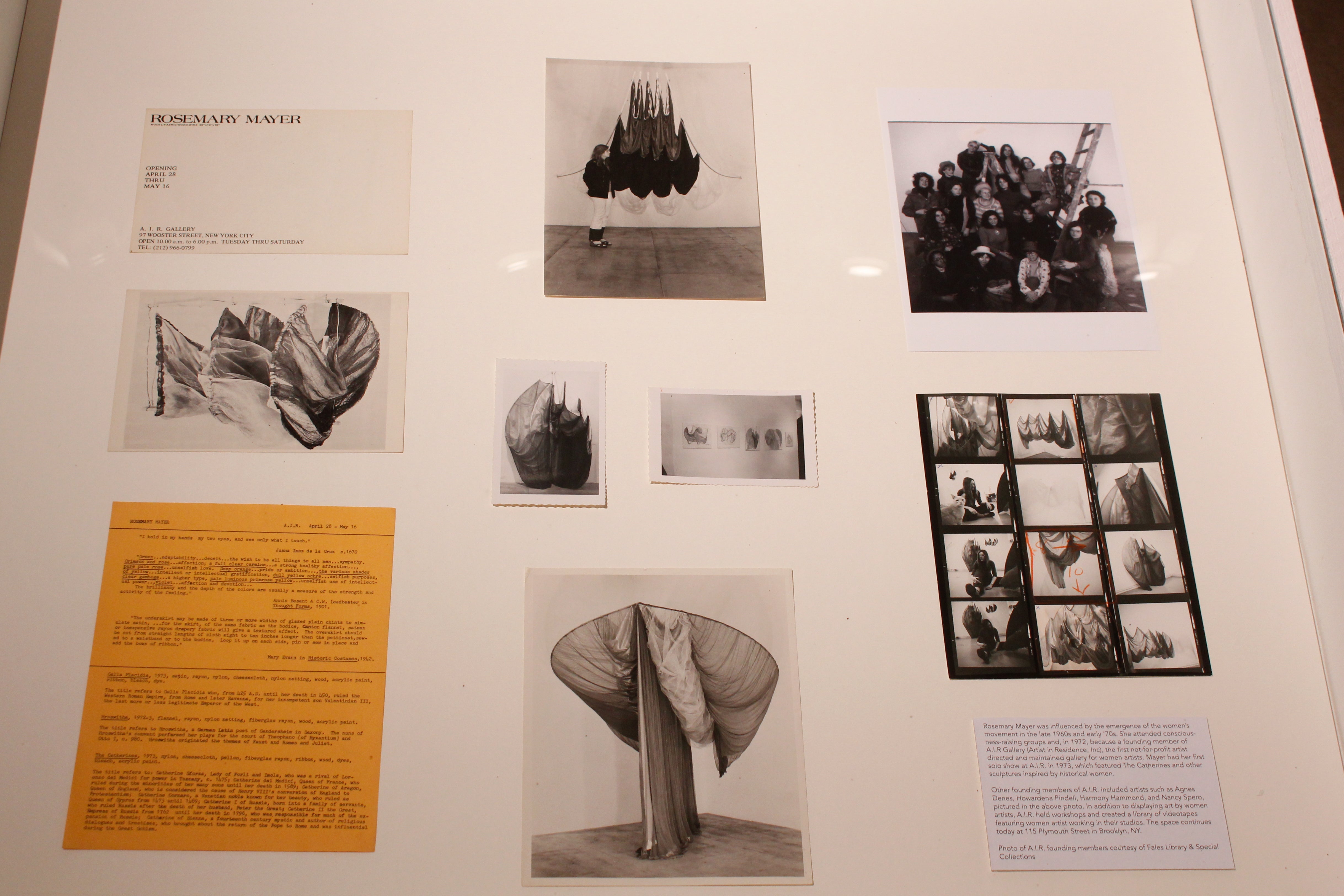

Steeped in knowledge of history, Mayer, among her many accomplishments, made art in various media, wrote reviews, and helped found the feminist A.I.R. Gallery in New York in the early ’70s. The exhibition at the Lamar Dodd School or Art [disclosure: I earned my Master’s at UGA] featured three fabric works — “sculpture, but not quite sculpture” as Geha describes it in her written introduction — by Mayer from the early 1970s alongside drawings, ephemera, and other contextual materials.

The exhibition, which included works made from 1966 to 1973, is best understood in conjunction with its catalogue of the same title, in which essayist Claire Barliant traces Mayer’s trajectory from conceptual practice to experimentations with fabric to her structural sculptures. Inspired by Sol LeWitt’s Veils, Mayer’s work from the mid to late 1960s is gridded, instruction-based abstraction. Then, announcing a return to sensuous materials, she questions the traditional supports of painting — canvas stretched over wooden frame. One of her transitional sculptures reproduced in the catalogue, Untitled from 1968, consists of raw canvas partially stretched over a wooden support, and partially loose, bunching and draping so as to expose its internal stretcher bars. It is midway between painting and sculpture. Such inquiry into the limitations of painting paved the way for the work she produced in the early 1970s.

The three large fabric works in the exhibition were the result of research and careful analysis of photographs of the artist’s work that is, by its nature, difficult to restage. Due in part to the materials, these are curatorially challenging works — a far cry from more traditional and more easily conserved sculptures in bronze, stone, or clay. Some of Mayer’s works are completely lost, only preserved through photographs.

The earliest of the three fabric works restaged for this exhibition, Balancing (1972), consists of warm-hued rayon draped on two horizontal rods strung from acrylic cord. It is the most minimal in both form and content, lacking the humanistic titling of the other two, which strive to connect the accumulations of cloth with historical women. The most dramatic of them, The Catherines (1973), has a budlike, organic form. Its analogous palette moves from fleshy pinks and golds to warm violet, the many layers giving the color a richness akin to glazes of oil, one on top of another, that produces a muted but dazzling quality. The title references Catherines of Western history: Russia’s Catherine the Great, Medici foe Catherine Sforza, and the more austere theologian Catherine of Siena. Given its title, the many layers of The Catherines further suggests the passage of time and the accumulation of associations that the name has acquired that extends far beyond the three cited here. The third fabric work Hypsipyle (1973) takes its name from a mythological Greek queen. Unlike the vertically oriented Catherines, Hypsipyle stretches outward horizontally and features moving wooden appendages. It was paired with drawings depicting, in precise contour hatch lines, its many folds and curves.

Influenced by Color Field abstractionist Morris Louis’s Veils, Mayer’s works are radically different in their approach to material: they are sculptural translations of painting freed of its traditional supports. They make manifest the transition from modern to postmodern in Western art. That is, while Louis’s dematerialized surfaces convey Greenbergian medium specificity and flatness, Mayer’s objects are dimensional accumulations of fabric that mimic another medium, painted folds of drapery. Coming directly from her category-bending processes of the late 1960s, they are resoundingly material things that bend to gravity and cast shadows.

Textiles are part of the decorative arts, that area long relegated to the bottom of the hierarchy of Western art history and are associated with femininity. The translucent veil, which inspired Mayer via Louis’s painting, has myriad associations with women’s bodies: to hide, ritualize, fetishize, and so on. For example, the lifting of the veil marks the moment a woman becomes married in Western culture. Conversely, the veil is the vehicle through which Salome, femme fatale par excellence, expresses her deadly, seductive power in the story of John the Baptist. Yet, I’m not convinced Mayer was — or wanted to be — critical of such associations. Mayer’s titles read as homages to famous women of history and mythology and suggest the essentialism of second-wave feminism of which Mayer was part.

I think there’s a better, more interesting and timely way to read Mayer. Given her stated interest in Mannerism and Baroque art, cloth may be read as an extension of the human form, translating emotion and spirituality into near-abstract color and form as is the case in Mayer’s muse, Pontormo, and his peers or Baroque artists like Bernini. Freed from a literal body, Mayer’s work made of translucent, moveable fabric expresses the values she seemed to most embody: experimental, transitional, elastic.

Mayer’s last works in the series, not on view at the Lamar Dodd School of Art but reproduced in the catalogue, culminate her interest in fabric as expressive material. Shekinah and Bat Kol (both 1973) are spindly constructions that look like the skeletal versions of her prior fabric work stripped of their voluminous textile bodies. Her interests changed, and her work followed suit.

The exhibition’s title came from a note on a photograph of Mayer’s last fabric work, Hypsipyle, but it reads like a manifesto. “Rosemary Mayer: Beware Of All Definitions” provided insight into an important artist from the past, but perhaps even more meaningfully, a model of how to work in various mediums meaningfully, and how to adapt as new ideas take hold. Geha calls it a “trajectory of mutability” in her introduction to Mayer’s work, and it’s perhaps especially potent in our own era: new media changes constantly and our economy necessitates a “slashy” approach to creative life and work. I think Mayer is exactly the kind of role model I was in search of when I was flipping through Pontormo’s journal in search of a path. I just couldn’t see her yet.

“Rosemary Mayer: Beware Of All Definitions” was on view through November 10.

Rebecca Brantley teaches art history at Piedmont College, where she is also director of the Mason-Scharfenstein Museum of Art.