Photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard called himself a “dedicated amateur,” despite a bevy of evidence that suggested he was anything but. He was the longtime de facto leader of the Lexington Camera Club, a rigorous and generative hobbyist group active from 1936 through the mid-70s that included members such as Van Deren Coke, Guy Mendes, Thomas Merton, James Baker Hall, and Jonathan Williams, among many others. He sought mentorship and instruction in his craft continually, both from members of the Camera Club (especially Coke) and from leading contemporary photographers of his day, attending workshops with Aaron Siskind, Minor White, and Henry Holmes Smith. Meatyard was also a notorious bookworm, devouring texts on diverse subjects ranging from Zen Buddhism to William Blake, Ludwig Wittgenstein to Noh theatre, all of which influenced the way he saw the world and examined it through his photographs.

Meatyard is most well-known for a body of work comprised of images taken in various locations across rural Kentucky depicting his family and friends arranged eerily in derelict structures wearing frightening rubber masks. The photographs are frequently read as explorations of body horror and the uncanny that sometimes possess a darkly comedic undertone. This interpretation is not altogether inaccurate but is instead simply too easy, given the artist’s strange last name and ironic birthplace, and insufficient when considering the rest of Meatyard’s artistic output.

On view at the University of Kentucky Art Museum through December 9, “Stages for Being” does a fair amount of work to recontextualize the artist’s contributions to photography and widen perspectives for understanding his legacy. The largest ever exhibition of Meatyard’s work in Lexington, it’s a necessary undertaking, especially since his photographs of masked figures make up a significant but by no means monolithic segment of his work. Indeed, when he died of cancer in 1972, Meatyard left more than ten distinct bodies of work, many of which were ongoing, including a series of documentary photographs of Lexington’s Georgetown Street neighborhood, images of tree branches meant to mirror calligraphic marks in his Zen Twigs series, and “no-focus” photographs that experimented with light and texture.

For “Stages for Being,” curator Janie Welker chose to focus on a regular tendency in Meatyard’s work: his use of intensely choreographed staging and theatricality. It’s not by accident that she chose the stage as a framework for understanding Meatyard’s photographs. Prior to moving to Lexington to work as an optician, Meatyard had been active in the theater department at Williams College while briefly studying there, and he maintained an active interest in the field afterwards, as is amply demonstrated by the images he produced. Figures are often organized in space to create palpable tension, and in many of the photographs, stare directly and intensely out at the viewer. Despite the fact that many of the images seem to depict families or people who are otherwise intimately related, none of the figures touch. Baby dolls and mannequin parts instead serve as substitutes for human intimacy.

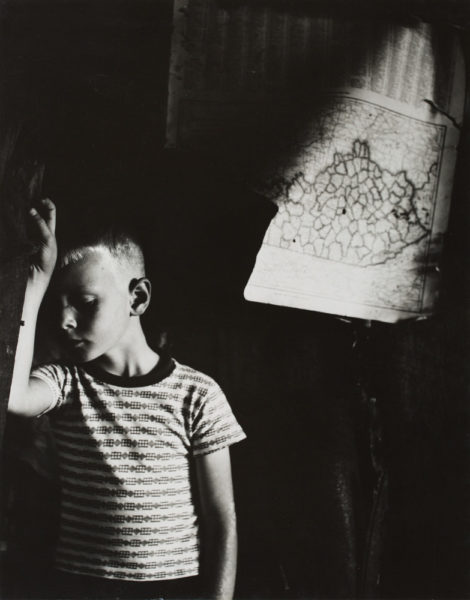

The dolls and mannequins are only a part of an extended collection of props loaded with metaphoric potential. In one image, a young boy stands under a laundry line holding a novelty rubber chicken in his left hand, while biting a large apple held in his right. Another, one of only a few in the exhibition that doesn’t include a human figure, shows a seated doll with frizzed hair, a dead bird situated stiffly across her lap, and a small bouquet of plastic flowers resting on the wall behind her. A third image shows an interior scene with a child immediately in view and a female figure in the next room back; this second figure is framed in light and seems to watch the child. The scene evokes an acute sense of anticipation similar what you may feel after seeing a bowling ball on a ledge.

The people in these photographs were posed uneasily and unnaturally according to Meatyard’s instruction from behind the lens, creating tense psychological relations between the depicted figures, objects, and space. The abandoned structures and overgrown landscapes that frequently serve as a backdrop for these images are as distinctly visually articulated and carefully framed as the figures and props. Meatyard was extraordinarily selective about the spaces he photographed, frequently scouting locations with other members of the Camera Club on weekends and envisioning how they would be populated. In this context, the masks frequently associated with his work also gain deeper meaning. Many of the visages Meatyard uses are drawn from flattened, easily recognizable character archetypes such as the Crone, the Hag, the Everyman, and the Innocent (who is, in this case, often represented either by unmasked children or dolls). By highlighting the exacting and deliberate theatrical staging involved in their creation, “Stages for Being” encourages more thorough readings of the photographs on view, unmasking the psychological potential Meatyard thoughtfully constructed within them.