The third incarnation of the New Orleans international art biennial “Prospect.3: Notes for Now,” curated by Franklin Sirmans of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, was framed in part by the 1961 novel The Moviegoer by Louisiana author Walker Percy. In the novel, the protagonist, Binx Bolling, undergoes an existential examination of the self, reflected in the setting of 1950s New Orleans. “The search” unfolds as he maneuvers on foot through the city, engaging with the characters and characteristics of various sections of town and the movie houses therein. He enacts “what anyone would undertake if he were not sunk in the everydayness of his own life.” With 58 artists in 18 venues (plus 50 satellite projects) that are spread throughout the distinctive neighborhoods and cultural institutions, large and small, of New Orleans, Prospect.3 viewers are given the opportunity to do the same.

Binx observes that the appearance of one’s hometown in a movie gives it “certified” status. He intimates that the movie house itself, in its own neighborhood setting, informs how one relates to and experiences the film. This premise clearly informed Sirmans’ curatorial philosophy for Prospect.3. He states at the start of his catalogue essay: “If you can’t smell, hear, and taste New Orleans at Prospect.3, then you are not experiencing the exhibition to its fullest.” Building on the foundation laid by Dan Cameron’s prior two biennials (the first, in 2008, an extraordinary love letter to the city, and a hard act for the second to follow), Sirmans’s third act firmly positions New Orleans as a unique and poignant place to evaluate Southern art, American art, and international art in all their captivating variety.

Akin to Binx’s transformative moviegoing experiences, engagement with the selected artworks—ranging from traditional photography and modern painting, to multidisciplinary site-specific installations and temporal performances—moves us beyond the everyday and into what he describes as a “Somewhere and Not Anywhere” space. As in The Moviegoer, the various biennial sites around the city are permeated by New Orleans’s rich political and cultural history. Traveling among them affords space and time for personal discovery and the ability to situate oneself in relation to the art and its broader significations. From the sweeping street views of distinct architecture, whether grand or derelict, to the exchanges with locals and art world insiders alike, the personality of the city becomes an ever-present springboard from which to dive deeper into a broader cultural conversation.

And, many pieces were made stronger for it. Analia Saban’s abstract sculptural paintings, one that includes a kitchen sink and another with a time-worn door, are arguably not her best work, yet they evoke a richer reading in the still palpable post-Katrina atmosphere of the city. Gary Simmons’s installation Recapturing Memories of the Black Ark, consisting of speakers placed a basic plywood stage (meant for an ongoing series of performances, with the first by the hip-hop artist Beans) would have been lackluster had it not been set in the Tremé Market Branch, a crumbling theater whose architectural interest did much of the performing.

A brilliant 2012 video installation by Carrie Mae Weems, re-presented for P.3, was perhaps the most literal interpretation of this moviegoing parallel. Playing in the historic McKenna Museum of African American Art, a Greek revival building replete with ornate ironwork, columns, porches, exposed brick walls, and creaky stairway, Lincoln, Lonnie and Me—A Story in 5 Parts makes for a truly transformative experience. The ethereal darkened place behind the curtain unveils a small seating area stanchioned off with velvet rope. Parted curtains reveal a bewitching holographic series of ghostly figures, including Lincoln, a minstrel emcee, a geisha, a boxer, a Playboy bunny, and a tap dancer, incrementally spliced with civil rights footage and a reenactment of the JFK assassination (taken from an earlier Weems video). A Delta blues soundtrack sets the tone. Speakers emit a number of gooseflesh-inducing voice-overs, including, “I want you to feel the suffering that I know,” and “revenge is a motherfucker.” The enigmatic montage is a haunting reminder of our darkest moments both national and personal, and an admonition of the racial and sexual injustices we endure and strive to surpass. It is impossible to leave the room unaltered.

Likewise, the hour-long performance by Andrea Fraser at the New Orleans Museum of Art, Not just a few of us, left an entire museum theater audience spellbound. Fraser embodied various real-life personalities from an actual 1991 New Orleans city council meeting in which Councilwoman Dorothy Mae Taylor put forth an ordinance to integrate Mardi Gras krewes. Derived from the session’s recordings, which Fraser studied and internalized, the performance seemed more like a possession. On a velvet-curtained stage, in a suit, and at a podium, Fraser became each character, taking on the personalities, intonations, and accents of 19 different people, all with the rapid fluidity of an auctioneer. Fraser’s presence—her perfect pauses, her quick and precise body language—not only served as cues to the personality switches but also kept the crowd hanging on her every word. And words they were. Every facet of each presenter’s often lengthy and complex point of view—from the absurd to the heartbreaking—was delivered from Fraser’s memory. The debate she reenacted sounded like something out of 1961 rather than 1991. Its more recent timeframe made it all the more dumbfounding.

The visual and historic significance of Carnival are on display throughout the biennial, including in another piece by Fraser, a sculpture made of Brazilian costumes heaped in pile, titled Um Monumento as Fantasias Descartadas (A Monument to Discarded Fantasies) at Tulane University’s Newcomb Art Gallery. This venue offers a trio of tightly curated rooms containing vignettes of work by British artist Hew Locke, Jamaican-born Ebony Patterson, and Iranian-born Monir Farmanfarmaian. Each artist adopted the beads, glitter, and sparkle of Mardi Gras in a splendor that belie more substantial points of view.

mixed media on paper, 40 by 120 inches.

Locke created a panorama of mythic figures composed in outline from black cording and beaded necklaces; titled The Nameless, it evokes all of the frenetic energy of a “second line parade” and the solemn drama of a jazz funeral (a panoptic homage to ancestry and the afterlife). The piece plays well off the adjacent gallery space, which features a selection of large-scale mixed-media works on paper by Patterson. Utilizing a deceptive visual vocabulary derived from pattern and decoration, Patterson layers jewel-toned swatches of color and texture to form dizzying collages. Like Locke’s installation, ominous undertones unveil themselves as floating figures, anonymous deceased men whose likenesses were extracted from Internet images, that emerge from the exotic landscapes. With Patterson’s bountiful embellishment, the collective lives of the nameless are honored and celebrated.

In an adjoining space, more than a half dozen wall-mounted mirrored and painted glass sculptures by Farmanfarmaian adorn the entire gallery. The basic outline of geometric forms, coupled with inlay of complex patterning, recalls both modernist aesthetics and Islamic ornamentation. The works appear timeless in their jewel box setting. Layered reflections (both of the viewer and nearby pieces) cast lavish and seemingly kinetic wall shadows. The concise and striking presentation of Farmanfarmaian’s pieces, as elsewhere in the biennial, amply represent the artist’s practice, while simultaneously remaining in conversation with other works in the gallery.

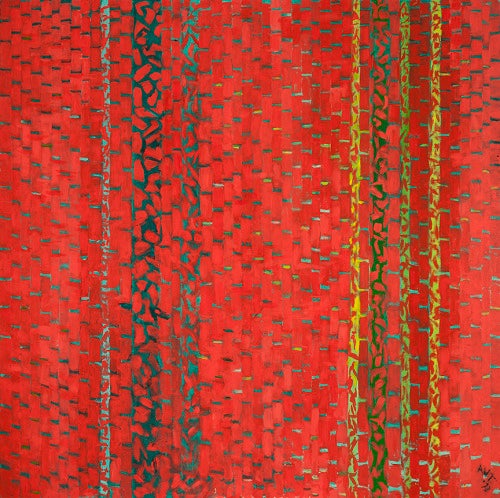

Sirmans repeatedly presents artworks in dialogue with modernism, including a number of historic pieces, as well as many that are influenced by the period. At the New Orleans Museum of Art (NOMA), for example, several abstract paintings by Ed Clark, Alma Thomas, and Huguette Caland hang in concert with one another. An impactful chorus within the biennial, the grouping signals a poignant overture to recognize talented figures who have been historically undervalued based on sex, race, age, or location. A number of abstract works from artists of various generations, including McArthur Binion, Theaster Gates, and Hayal Pozanti (all at the Contemporary Arts Center) infuse the visual vocabulary of modern painting with timely personal and communal narratives.

The notion of looking back to look forward prevails in almost every biennial venue. Sirmans’s selections and juxtapositions perpetually pose the questions: “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” At NOMA, one must traverse historically focused permanent collection galleries to locate specially presented works by Paul Gaugin (French, 1808-1903) as well as Tarsila du Amaral (Brazilian, 1886-1973). Gaugin is perhaps the art historical poster-child for seeking identity within the realm of the Other, while du Amaral was involved in the collective Movimento Antropofagico, which sought a non-hybridized Brazilian aesthetic identity. Their inclusion enriches the reading of the contemporary selections, providing a historic foundation for the international scope of the show. They also serve as early examples of artists’ constant search for awareness beyond borders and desire to locate a reflective standpoint from which to express their place in the world.

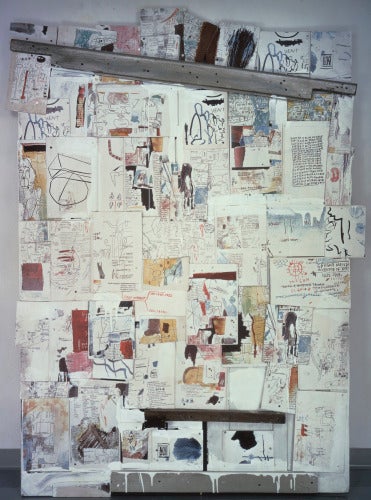

Nowhere was this more apparent than at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art’s “show-within-a-show” of 10 works by the Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), titled “Basquiat and the Bayou.” Pieces from various periods in the artist’s career showcase imagery and text sourced from the Deep South’s cultural landscape. Sirmans’ wall didactic aptly describes the exhibition as “representing Basquiat’s internal fight with the shadows of the American South, shaped by a long history of slavery, colonialism and imperialism,” noting that it “explores themes of geography, history, and cultural legacy in Basquiat’s work.” Among the highlights are Natchez (1985), referencing the earliest Louisiana settlements, and King Zulu (1986), with evocative imagery relating jazz, blues and Zydeco. The show is a pinnacle example of how the history and influence of the region is an ever-pervasive force for aesthetic and conceptual artistic expression.

These types of syncretizing mashups abound at the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC), a central hub for the biennial. Three floors house a combination of local, national, and international artists, often in the same room. Points of view from Asia (for example, Pushpamala N.), Africa (Pieter Hugo), Europe (Mohamed Bourouissa), and the Middle East (Manal Aldowayan) are presented alongside American (and sometimes New Orleans-based) artists, such as Thomas Joshua Cooper, Sophie T. Lvoff, and Charles Gaines. Discourses both personal and political—ranging from oppression, disenfranchisement, and incarceration, to private and public histories and cultural mythologies—are portrayed with raw honesty. Their aesthetic and conceptual grit is mirrored by the unfinished warehouse space of the CAC. Works here do not have the majestic aura found within the Tulane galleries, instead they are presented in the architecturally challenging spaces of corners, curved walls, and carved-out byways that serve to strengthen their impact.

A showstopper among them is Los Angeles-based Glenn Kaino’s awkwardly configured installation Tank, a piece that is one part aquarium and one part war zone. Various coral species covering numerous resin-cast army tank parts at first glance seem to be peacefully cohabitating in water-filled glass boxes. The various appendages of pumps and pipes evoke concepts of manufacturing, ecological systems, and, of course, post-Katrina destruction/reconstruction. Moreover, the work’s elicitation of violence, war, and the struggle for terrain is made all the more poignant with its submersion in the deceptively alluring aquatic landscape.

Other buzzed-about projects include the Propeller Group’s Shine at UNO’s St. Claude Gallery, which makes striking connections between funerary practices in New Orleans and Vietnam; New Orleans-based Tameka Norris’ film installation (with Garrett Bradley) Meka Jean: How She Got Good at May Gallery, which draws parallels between the growth of the city simultaneous to her alter ego’s rise to art stardom; and, at NOMA, Jeffrey Gibson’s myriad highly stylized sculptural works combining materials traditionally associated with Native American adornment with those of pop and club culture. These are just a few examples of the woven layers of the historic and contemporary, regional and global, personal and public that are sometimes embodied in a singular practice and that thread through “Notes for Now.”

Community involvement in the biennial is not to be overlooked. One superlative example is the multiphase and multifaceted Home Court Crawl/Blights Out by Lisa Sigal. Created in collaboration with playwright Suzan Lori-Parks, the nonprofit organization Blights Out, as well as local architects and urban planners, Sigal turned derelict houses into poetic and prophetic calls to action. On the broader scale, the overall coordination with places and spaces officially and unofficially related to the biennial entails a series of administrative and logistical feats that cannot be overstated. It is important to emphasize that without community support and buy-in, the authenticity of this endeavor would cease to exist.

Many observers have wondered whether, without the catalyzing good will of more immediate post-Katrina attention, the Prospect series would continue to be meaningful. While those issues may still be relevant, “Notes for Now” proves that the region’s overall richness continues to be fodder for creativity.

“Notes for Now” is a living exhibition. As performances and events continue to take place, this biennial will evolve, and audiences will continue to affect it and be affected by it. Throughout the remaining weeks and months, interpretations will change, critiques will challenge, and new contexts will emerge. Just as time has deepened the impact of Gaugin and Basquiat, it will surely make art historical figures of many of the contemporary artists in the show. Others will fall afield.

The biennial is free and open to the public through January 25, 2015. It is not to be missed. It marks a moment, however fleeting, that embodies so much of what is relevant today. Prospect.3 is another gift to New Orleans, to the South, and to the broader art community. As Tavares Strachan’s floating 50-foot neon beacon that travels up and down the Mississippi River foretells, “You Belong Here.”

Melissa Messina is an independent curator who divides her time between Savannah and Atlanta, Georgia, and Brooklyn, New York.