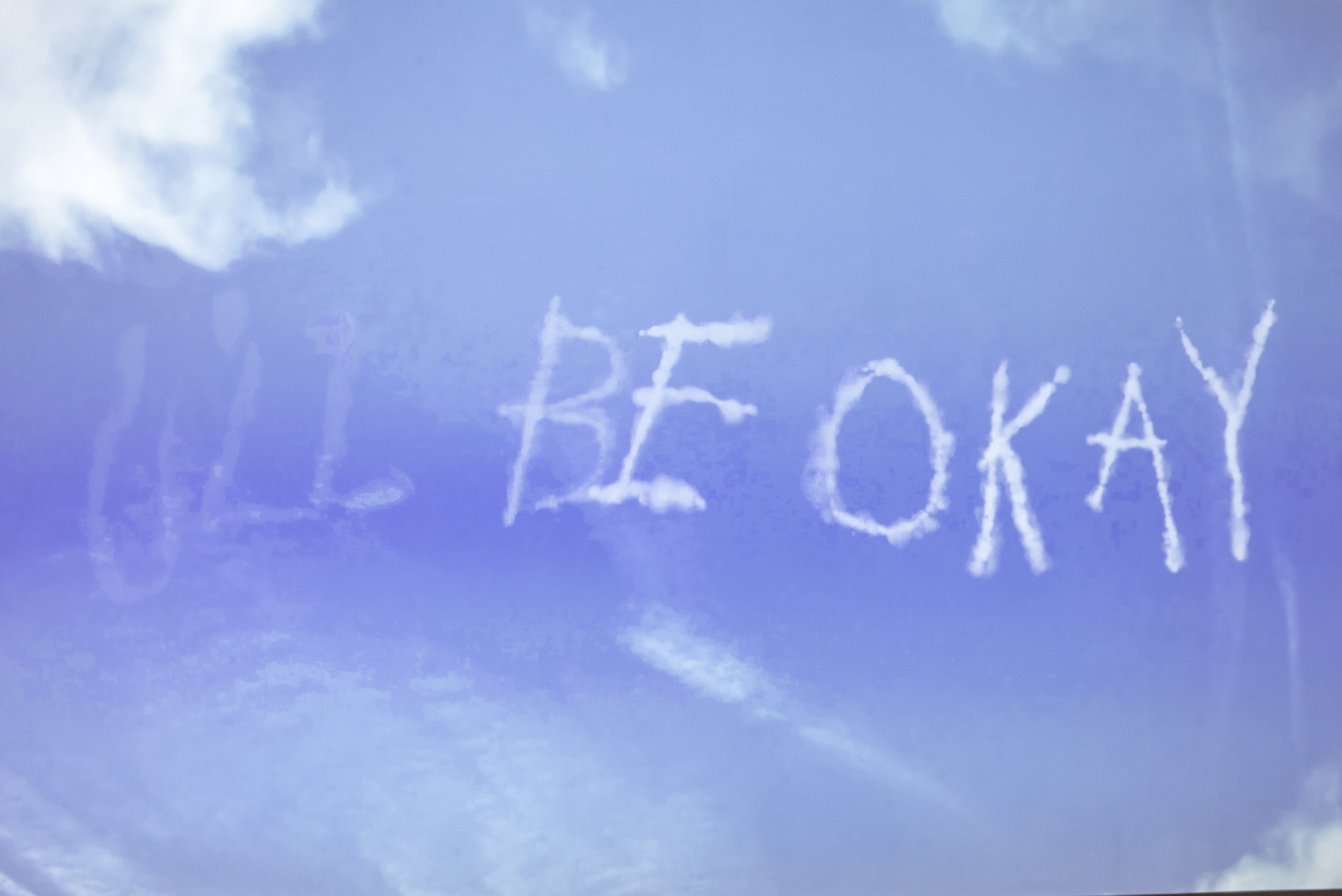

You’ll Be Okay, 2014, digital animation, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.” width=”6016″ height=”4016″> Jillian Mayer, You’ll Be Okay, 2014, digital animation, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Photo: J Caldwell)

You’ll Be Okay, 2014, digital animation, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans.” width=”6016″ height=”4016″> Jillian Mayer, You’ll Be Okay, 2014, digital animation, at the Contemporary Arts Center, New Orleans. (Photo: J Caldwell)Some days the clichés of New Orleans are so cloying, like the number of fake second lines snaking through the French Quarter, that residents cringe. Locals chafe under the mythologizing of New Orleans, and that becomes a problem when the Prospect triennial rolls around every few years and resurrects the tropes in order to offer work that fits the city. Usually a fake second line opens the big show, but this year the exhibition tossed the cliché and opened with a performance by P.4 artist Naama Tsabar.

It featured twenty-one local female musicians standing on amplifier pedestals that had been arranged in a big triangle in the middle of Washington Square Park, just down the block from the jazz clubs on Frenchmen Street. Each musician was dressed differently, such as a bass player in a New Orleans Saints football jersey and black high tops bedazzled with gold studs, and a guitarist in a flowing floral dress, short cowboy boots, and a big hat. The music built slowly, rotating through each leg of the triangle until all of the musicians were playing at the same time. Then people started to cross the threshold and enter the triangle. Soon everyone was swarming around the musicians, usually with cell phone in hand to take panoramic video. The sun was shining, it was warm and windy, and it had started to sprinkle just a little bit before the performance began. I had that out of body experience that great music evokes, and the catharsis felt communal. Tsabar’s performance proved that some days, the clichés recede and the magic of New Orleans inspires.

The New Orleans triennial is leaner this time around — Prospect.4 has more artists than the 2014 edition, Prospect.3, but uses fewer venues. The smaller footprint makes the logistics of getting around in New Orleans a bit easier, though it still took me three days to see almost everything. The 73 artists are spread between 17 venues, with most concentrated at the CAC (Contemporary Arts Center), the Ogden Museum of Southern Art, NOMA (the New Orleans Museum of Art), and the Old Mint (the New Orleans Jazz Museum).

There are certain tropes in Prospect, and this iteration checked them all off. Bring in lots of artists from around the globe, and toss in a few from New Orleans. Of the locals, choose one who made it big and left the city (Wayne Gonzalez), some who are central to the scene (John T. Scott, Quintron, a garage tinkerer musician, and Miss Pussycat, his partner in crime, a beloved maker of subversive puppet shows); and some who are emerging (Jennifer Odem, Michel Varisco, Monique Verdin). Fill out the roster with a few big names — Mark Dion, Kara Walker (whose installation was postponed until the closing in February). Finally, include a long-dead artist to shake up our assumptions about contemporary art biennials. Here, it’s Louis Armstrong, the beloved musician from New Orleans who also made collages on his master reel boxes with cutout photographs of himself and other people in his circle, as well as bits of ads and other ephemera. Armstrong also showed up as the topic of Penelope Siopis’s World of Zulu and its accompanying video Welcome Visitors: Relax and Feel at Home, which explores Armstrong’s visit to Zimbabwe in 1960.

In addition to celebrating New Orleans and citing its unique history, Prospect tends to use the city to connect to the theme of the Global South. Runo Lagomarsino’s text piece at Crescent Park is particularly funny in that respect: on three panels, it reads “If you don’t know what the South is / it’s simply because / you are from the North.” This year, much was made of Prospect coinciding with the 300th anniversary of the city in 2018, and several artworks did engage that history. No local art viewers would be surprised that the show included Mardi Gras Indian costumes, featured in a thoughtful installation of Darryl Montana’s work that included contextual photographs by Prospect veterans Keith Calhoun and Chandra McCormick. Prospect also tends to succeed with site-specific work, and Odili Donald Odita’s project Indivisible and Invincible: Monument to Black Liberation and Celebration in the City of New Orleans is a good example. Odita designed abstract flags that are installed at several locations associated with African-American history, from Dooky Chase’s restaurant to the Algiers ferry — and I recommend a sunset crossing on the ferry in order to see the work. Works by Derrick Adams and Yoko Ono are displayed on the riverfront streetcar line, and Pedro Lasch is showing a site-specific work at M.S. Rau Antiques, a well-known store in the French Quarter that is a cultural landmark. Titled Reflections on Time, it offers an intriguing commentary on time and illusion by using black mirrors to pair images in the mirrors with clocks and other objects from Rau’s collection.

Prospect.4 curator Trevor Schoonmaker, who is the chief curator at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, has titled this year’s edition “the lotus in spite of the swamp.” The unfortunate wording could imply that the art rises out of the dirty swamp of New Orleans, but the curator insists that it refers to how the greatest art can emerge from difficult circumstances — thus the title’s derivation from saxophonist Archie Shepp’s description of jazz, as well as Hindu and Buddhist symbolism. Schoonmaker sees our current circumstances as the setting for a new blossoming. The rhetoric emphasizes the sense that artists are responding to a crisis, delineated as environmental, social, and political. While I expected that timing to mean political art of a strident variety, it has actually resulted in moments of tenderness. “Healing” was the word of the show—an emphasis on using catharsis to counteract the negative. Or, as Jillian Mayer’s video proclaims, You’ll Be Okay (2014), the words appearing as if written by a skywriter, but actually a product of digital animation.

The works alternate between deep and fun, giving visitors moments to ooh and aah while also bringing some to tears. Xaviera Simmons started her artist talk at NOMA by saying, “I thought we were much further [along] as a country.” She argued that “the country itself is a kind of heartbreak and New Orleans encapsulates that.” Simmons spoke about how the city demonstrates the cycle of “generational wealth and generational poverty” that feeds the divide between the neighborhoods with expensive houses and crystal chandeliers versus the ones that have poorly maintained and crowded housing. She was tearfully honest about her feelings at this particular moment in time: “I’m really upset.” Her work on view appropriates text from political speeches, notably Michigan Representative John Conyers’s speech about H.R. 40, a current bill that would study the legacy of slavery and make recommendations for reparations to African-Americans. In Rupture (Edition Two), Simmons painted the text of Conyers’s speech onto long wood strips that completely fill one wall of the gallery — and that she admitted was designed to be Instagram-friendly to reach a wide audience. The North Plays Innocent and Points at the South (Landrieu 2017) borrows the text of Mayor Landrieu’s speech about the removal of Confederate monuments in New Orleans (listen to his speech here), a topic parallel to photographs by Kiluanja Kia Henda’s Homem Novo series (2011-12), in which people pose on the empty plinths that once held statues of Portuguese rulers in Angola.

It was the shock of encountering a work about the Emanuel AME church in Charleston that made me emotional — a place that I have written about before (you can read it here). In Jon-Sesrie Goff’s A Site of Reckoning: Battlefield (2016), spoken word narration by Sonia Sanchez and the gospel music of Sweet Honey in the Rock accompany a 5-minute long black-and-white video about the shootings at the church on June 17, 2015. The camera follows a car pulling into the parking lot behind the church, and I’m guessing that only a Charlestonian like me would catch that the car was pulling up to the side entrance that Roof used to enter the building. The camera takes us into the sanctuary and lingers on still tableaux: the organist’s mirror, the eagle finial on a flag, the objects on the altar. Then the camera zooms in on details of the offerings left behind: votive candles, handwritten messages of love and support, sweetgrass roses hanging from a tree, a plaster angel, coins left on top of the church sign. In the spoken word narration, Sanchez implores us to “come to this battlefield called life,” exclaiming “we need your hurricane voices.” Finally the camera pans out to show the front of the church—no people at all, just flowers and stillness as the music ends and the only sound is the sound of passing cars.

Goff’s video makes the church real for those who have never visited it, and the video offers an emotional sanctuary — a place to memorialize the loss of life. It refuses to show us the violence at all, and that was another theme of work in Prospect.4: the question of representation. In her artist talk, Njideka Akunyili Crosby talked about how representation is founded on the absence of the thing being represented, and how she used that idea in her collage paintings about the history of Nigeria. Alfredo Jaar has considered the logic of representation in photography throughout his career. Prospect.4 includes Jaar’s One Million Points of Light (2005), which is an image of the sun sparkling on the water off the coast of Luanda, Angola, the site where African slaves were shipped to Brazil beginning in 1538 — information provided by text on an accompanying take-away postcard. The image serves as an abstraction of that history. Historians have argued that photography has been used as a tool of control, used to surveil or victimize its subjects. In Prospect.3, Carrie Mae Weems used that history to reflect on the absence of the black body in history, especially in her 2003 series The Louisiana Project. For P.4, the installation of Barkley Hendricks’s life-sized portraits of African-American subjects in the atrium at NOMA successfully used the institutional authority of the museum to counter the lack of the black body in the history of painting.

John Akomfrah’s new film Precarity is a highlight of the exhibition, and demonstrates the project of making the absence at the heart of representation present. The film is inspired by Buddy Bolden, considered to be the inventor of jazz but who never recorded in his lifetime. The 45-minute film is shown on three adjacent screens and is structured around the six properties of double consciousness according to W.E.B. DuBois. Wearing a bowler hat, Bolden looks out onto the landscape or straight at the viewer with a sense of deep sadness. Much of the film imagines Bolden’s life in different spaces: in a fancy house (perhaps a brothel in Storyville, where jazz musicians often played), in a slave cabin, in a vast industrial space, straightjacketed in an institution. This imagined reconstruction is based on the few documents about him, such as a newspaper clipping about him striking his mother-in-law with a water pitcher, after which “he was never seen in public again,” and period photographs shown floating on water. The rhythm of the musical soundtrack and poetic narration is matched by the movement in the period footage—of streetcars on Canal Street, of carnival rides at the 1893 Chicago World’s Fair, of workers in factories and unloading big ships, of Mardi Gras parades in the French Quarter. In the soundtrack, we hear bits of what locals call “traditional jazz” (Dixieland), the type of music that Bolden would have played, but we don’t see Bolden play until the end. The different musicians that we’ve met throughout the film then finally converge on the small stagelike space of Perseverance Hall, a site of pilgrimage today for preserving the legacy of musicians like Bolden, but when they play their instruments, we hear nothing—an absence that sings.

In contrast to these moments of deep reckoning, the exhibition also assumes that viewers are like cats. Dangle something sparkly in front of a cat, and it will jump. Schoonmaker refers to it as the “maximalist aesthetic” of New Orleans — the sparkle and awe of Mardi Gras. Two sculptures by Rina Banerjee and Lavar Munroe — the latter’s of which depicts a rider who has fallen off a giant horse, made from Carnival leftovers — provide the wow factor on the first floor gallery of the CAC, and even the two works that look abstract are actually interactive sound pieces hooked up to an amplifier (Naama Tsabar’s Work on Felt series). Evan Ifekoya’s Disco Breakdown (2014) is a fantasy response to the depressing litany of our social media newsfeeds. Ifekoya suggests that a dance party is just what we need — a break from the overwhelming present. And the music really was catchy. What better way to access the Mardi Gras sense of spectacle than to install a disco ball at the CAC?

These spectacle moments are countered by the quiet pulsing of water. I found Donna Conlon and Jonathan Harker’s The Voice Adrift (Voz a la deriva) late in the day, feeling out of energy, and I was mesmerized. The video starts with a thunderstorm — the rain from which carries a blue water bottle through the streets of Panama. It bounces against the curb and finds high drama when it enters a storm drain. Yes, it’s about the environment and the horrors of plastic, but the subtlety of that message is what makes it work. Jeff Whetstone’s project at the UNO St. Claude Gallery explored the life of the batture, the strip of land along the shore of the Mississippi River that often floods. His video, The Batture Ritual, shows giant barges coming down the river as local Vietnamese men fish from the batture, and the photographs in the gallery show the results of their work, such as a big catfish filleted and covered with neon green flies. Jennifer Odem’s Rising Tables is installed on the batture and viewable from Crescent Park. The stacked antique tables play with the wording of water tables and rising sea levels, as well as the history of attempts to control the Mississippi River. Also in Crescent Park, Radcliffe Bailey’s Vessel offers an intimate space of reflection that is minimalist in comparison to his other work. The round steel enclosure fits only a few people at a time, and viewers inside look at a single large conch shell (familiar from his previous work), installed just below the open roof, while listening to audio of classical cello music.

These allusions to the role of water in New Orleans, to jazz music and its link to the city, to the current politics of race and gentrification all seem to follow the formula that Prospect has used in the past. There are a number of New Orleans residents who have wondered: couldn’t Prospect bring us the kind of art that does not fit the city, that challenges us in new ways, that exposes us to new things? Perhaps Prospect.5 will go there. But at the end of the day, in this shifting political landscape, the formula does make for an interesting show. The exhibition offers a moment of unearned grace, unearned because the tropes are tired for a local or regional audience, and tend to work best with the out-of-towners who are still in awe of the city. Yes, some of the nods to the clichés fall a little flat, but the surprising thing was how many did not.

Rebecca Lee Reynolds is a lecturer in the department of art & design at Valdosta State University, where she teaches art history.