Click here to order BURNAWAY #2: EXCHANGE!

“When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South” is on view at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston, through May 10. This review is of the show’s debut at its organizing institution, the Studio Museum in Harlem. The exhibition has also appeared at the Nova Southeastern University Art Museum in Ft. Lauderdale.

The American South is a geographical locale and a cultural construct like no other. You don’t necessarily have to live or work there in order to engage with its unique sociopolitical situation or be seduced by its outsized mythology. That fundamental notion is one of the central premises of “When the Stars Begin to Fall: Imagination and the American South,” on view at the Studio Museum in Harlem last spring. Organized by the museum’s assistant curator Thomas J. Lax, the exhibition explored the relationship of the black experience to notions of “The South” in works by artists who actually reside there and others who are simply drawn to Southern lore and aesthetics.

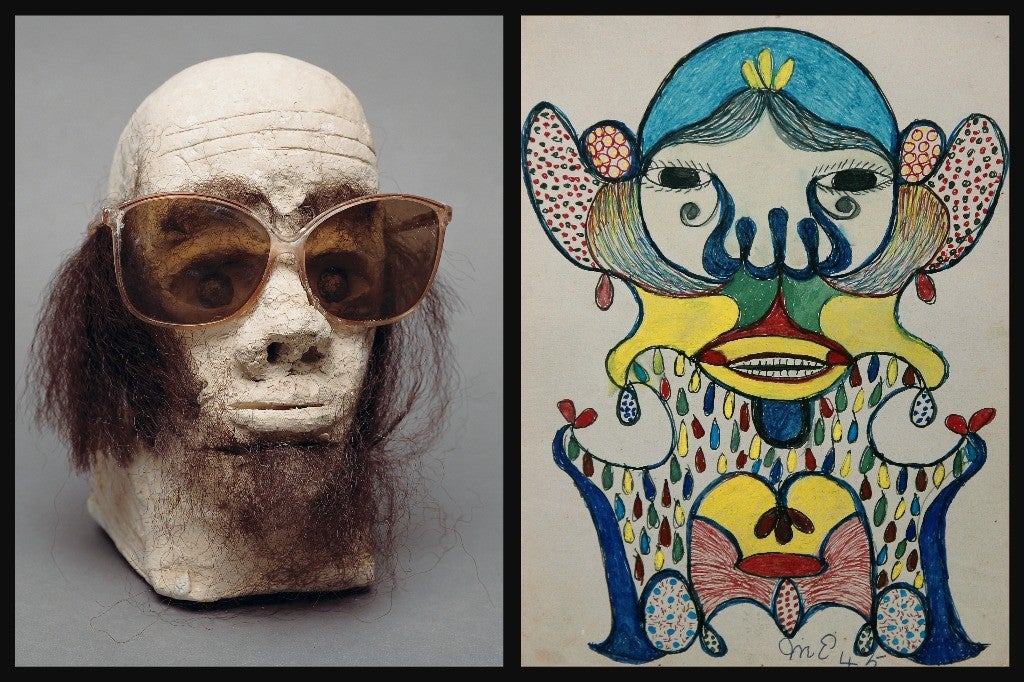

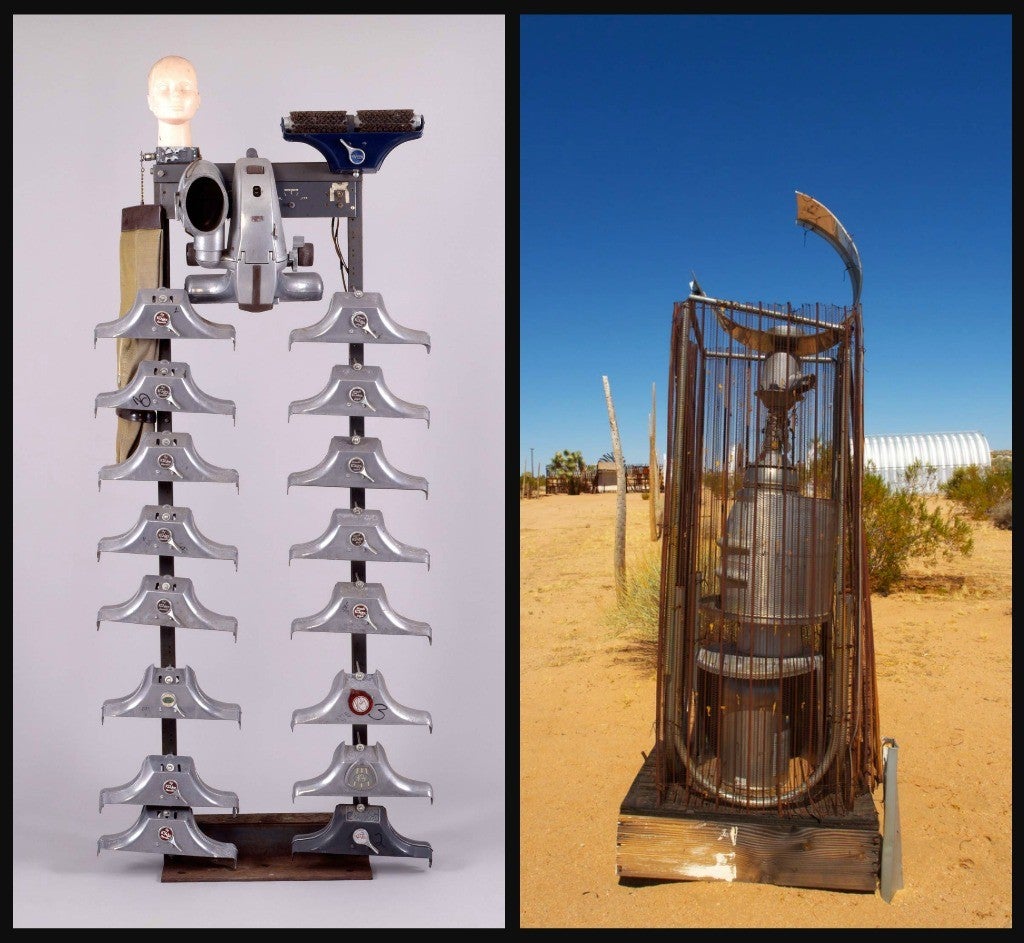

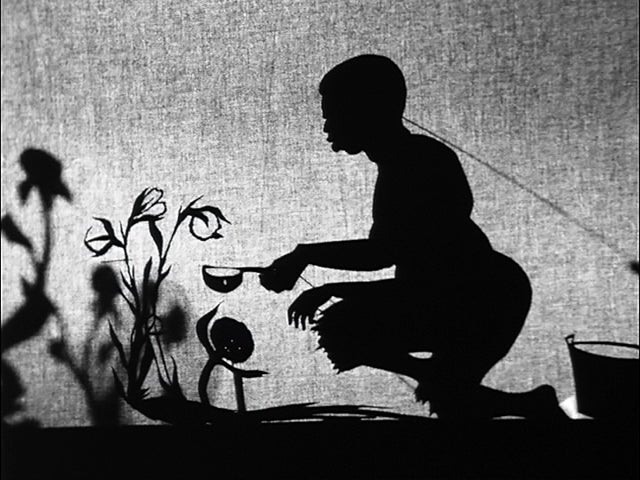

Nearly upstaging the show’s central premise, but adding a great deal of excitement to the proceedings, was an almost combustible juxtaposition of works by insider and outsider artists. The sprawling exhibition featured some 120 pieces by 35 artists, including the well-known Theaster Gates, David Hammons, Kara Walker, and Carrie Mae Weems, and familiar outsiders such as Lonnie Holley, Thornton Dial, Bessie Harvey, and Minnie Evans. The importance of “When Stars Begin to Fall” was in its bold effort to further dissolve the boundaries that once strictly divided insiders from the outsider genre. Lax’s strategy is part of an international curatorial trend, perhaps most prominently realized in last year’s well- received Venice Biennale curated by Massimiliano Gioni of the New Museum in New York.

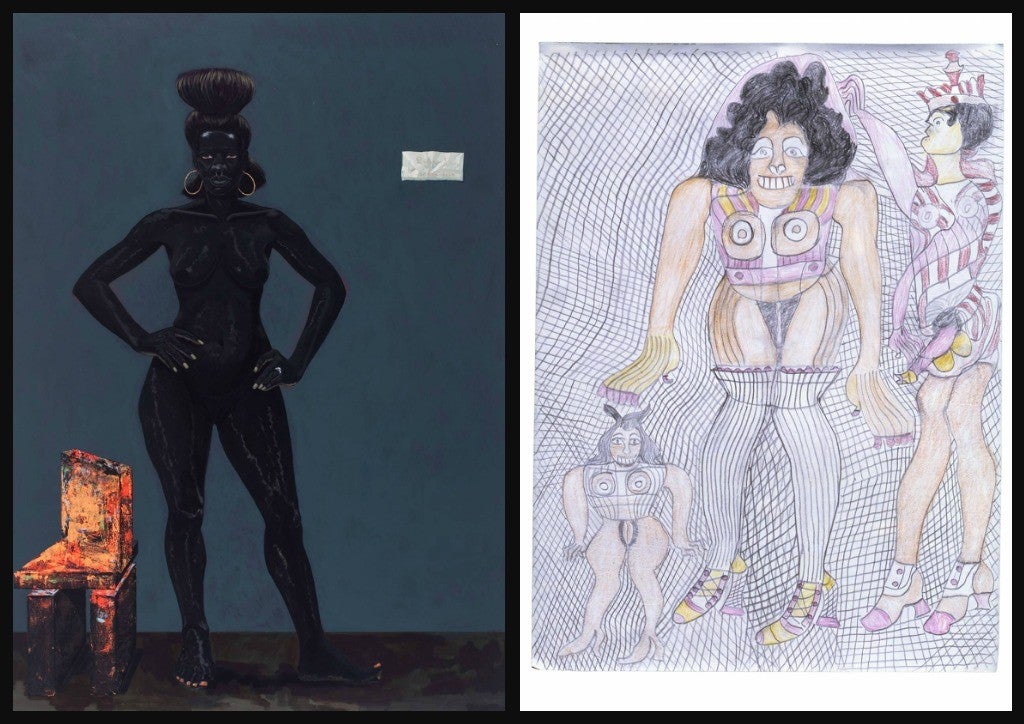

Among the highlights of “When the Stars Begin to Fall” were Kerry James Marshall’s large (approximately 7 feet tall) 2009 paintings Frankenstein and Bride of Frankenstein, which recast Mary Shelley’s and Hollywood’s monsters into African American slaves. In a wry comment on 19th-century racial conflicts, Marshall presents these imposing nude figures as rather menacing outsiders. They correspond most intently with Bessie Harvey’s nearby large-scale assemblage sculptures made of found wood, painted and embellished with found objects. Her 1985 Black Horse of Revelations, with its black-painted and twisted tree roots, adorned with chains and strings of colorful beads, is similarly aggressive, but with a more spiritual aim, conveying the metaphysical aspects of nature in terms of a religious offering.

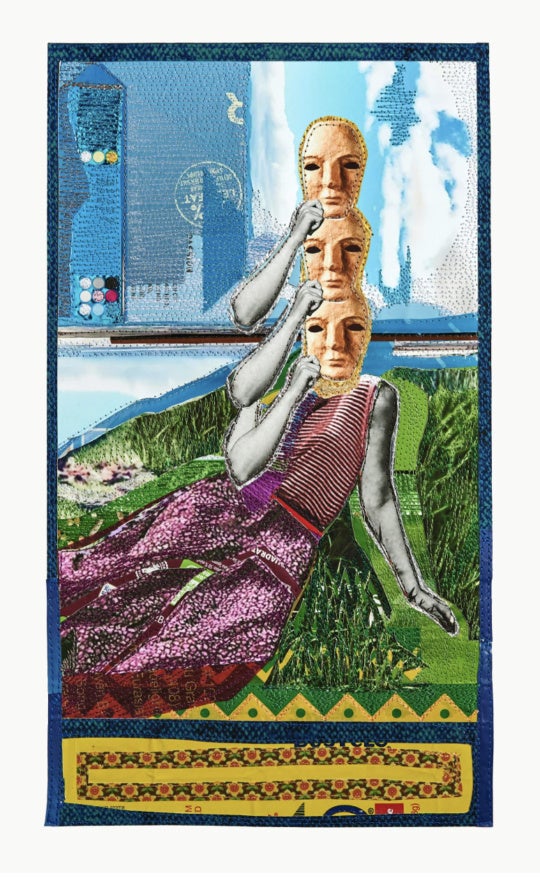

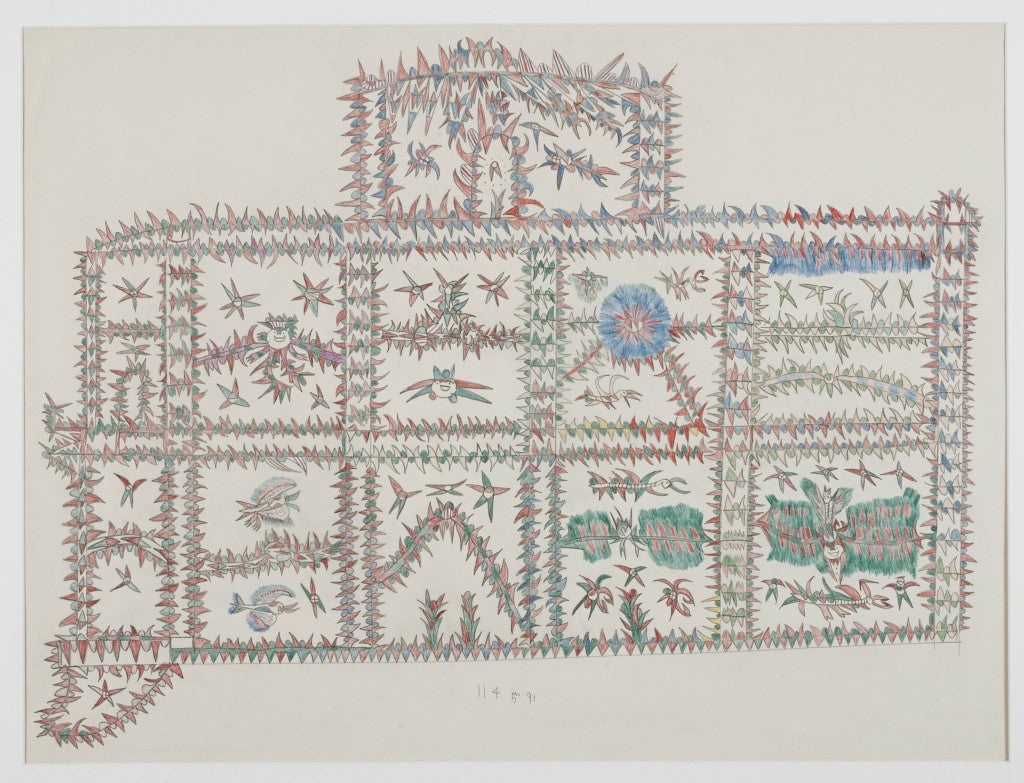

Also having a spiritual intent, but much more intimate in terms of scale and detail, are the intricate colored pencil drawings that Frank Albert Jones produced in a Texas state prison during the 1960s. He had been convicted of rape and murder, crimes for which he always maintained his innocence. Belying his violent biography, the delicate compositions he created, which he called “devil houses,” closely resemble refined folk-art embroidery. In this show they formed an unforgettable liaison with a set of neighboring works, some richly textured and colorful abstract textiles produced by Marie “Big Mama” Roseman, a Mississippi midwife and seamstress.

25 by 35¾ inches.

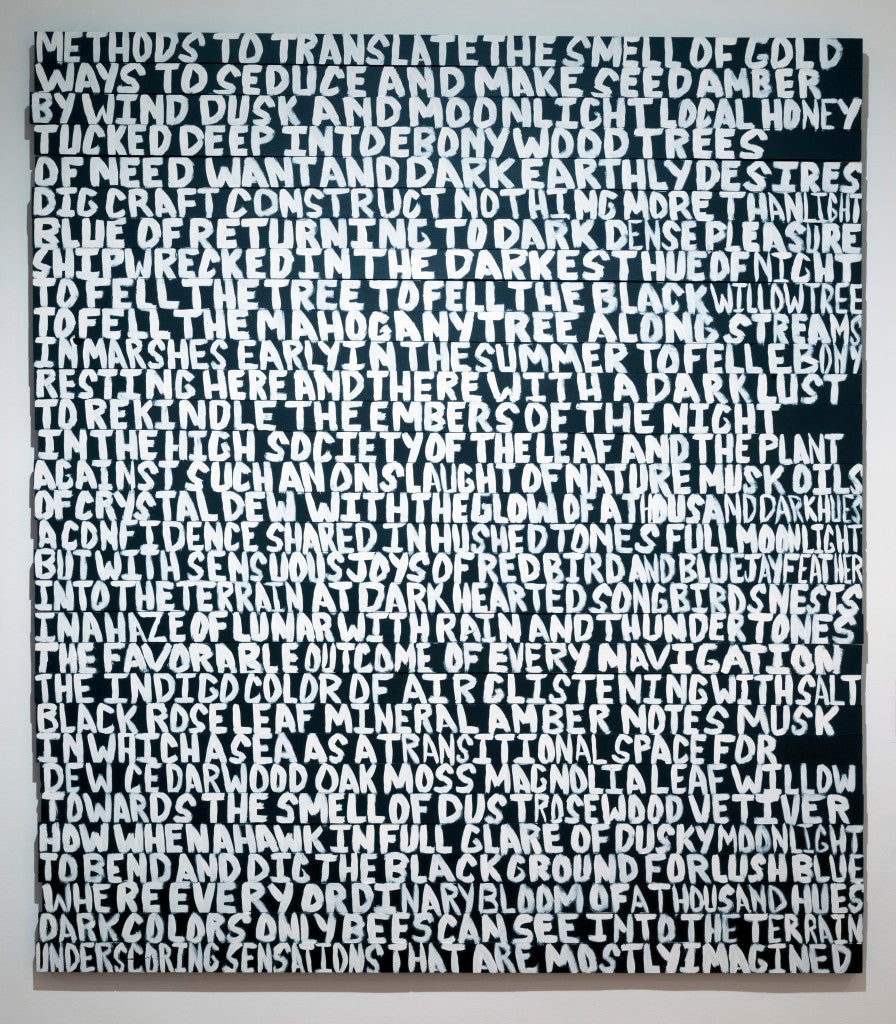

13½ by 20 inches. Courtesy Jack Massing.

The Canadian-born, New York-based artist Deborah Grant is known for constructing elaborate narratives based on extensive research into the life and work of artists—some obscure, others well-known art-historical figures. In this show, she presented a 24-part work, in mixed media on wood panels, exploring the life and art of painter William Henry Johnson, who died in 1970, after spending his last 30 years in a Long Island psychiatric hospital. Each panel reimagines an episode in the life of the artist, whose style she adapts as her own for this work. It’s a moving tribute that demonstrates the powerful influence outsiders have had on new generations of savvy trained artists like Grant. The exhibition offers a rare comparison between refined works like Grant’s and the visceral, raw expressions conveyed, for instance, in drawings by the late Tennessee self-taught artist couple, Henry and Georgia Speller. The highly personal and psychosexual dramas they depicted are similarly potent but far removed from the filter of art history that Grant manipulates with such finesse.

Correspondences and formal relationships like this one abounded in the show, and they helped to render obsolete the indomitable parameters and limitations that critics and curators once assigned to outsider art. Titled after the eponymous spiritual song recorded by the Seekers, the Weavers, and others, “When the Stars Begin to Fall” at first seemed to be a hodgepodge of thematic concerns and formal processes. But the intensity of the works was consistent, as was each artist’s evocative Southern vision.

David Ebony is a contributing editor of Art in America, senior editor at Snap Editions, and a freelance writer based in New York.

CLICK HERE TO ORDER BURNAWAY #2: EXCHANGE.