To be sure, “Darkness Invisible,” a group exhibition on view at Tampa’s Tempus Projects through May 1, is squarely centered on the figure. However, proper portraits and straightforward physical depictions are noticeably absent. As a point of departure, artist curators Justin Bryan Nelson and Tracy Midulla Reller cite a Victorian photography technique known as the “hidden mother,” whereby mothers would be concealed while holding their child still for the long exposure times required in early photography. The parent was often hidden poorly, simply draped with a cloth, for example. To a modern eye, the effect is somewhat unsettling. However, in light of current apprehensions over surveillance and online anonymity, the anxiety incited by a subject that is present yet not present takes on a particularly contemporary quality.

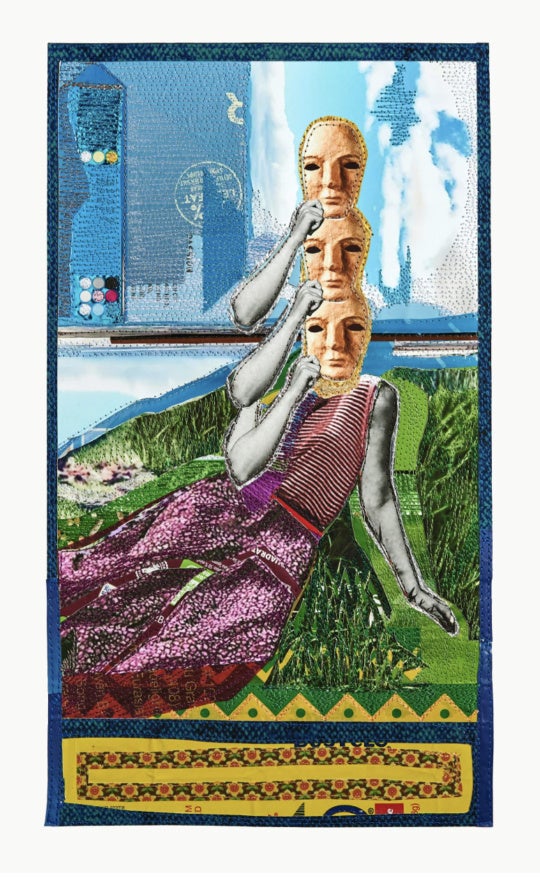

While self-image and post-selfie portraiture is explored in pieces by Gigi Lage and LA-based Amir Fallah, current concerns are perhaps most overtly felt in Noelle Mason’s Mule (HKD/ORD) (2007). A United Airlines boarding pass, a Buddha figurine, and a gallery invoice are displayed in a shadow box beside a pelvic X-ray of the artist, the same figurine glowing white at the image’s center. The information card elucidates the collection of items, describing the medium as “Elephant ivory smuggled vaginally from Hong Kong to O’Hare, x-ray.”

Essentially documentation of a performance, the work’s antiseptic presentation does not dampen its visceral impact. Upon seeing Mule (HKD/ORD) during the exhibition’s opening and realizing the nature of the figurine’s international journey, several gallery visitors visibly winced in empathetic discomfort. Each component forcefully points to the artist’s body. Even the title of the piece refers not to any of the items mounted on the gallery wall but to the human body acting as an illicit form of transport. Still, Mule (HKD/ORD) refrains from explicitly depicting the figure of the artist (the X-ray, arguably, an image of the figurine). This reflects the sure ambiguity of the artist mid-flight, her inconspicuousness among fellow travelers essential to evading unwanted attention and the success of the performance.

In a painting by Atlanta-based Sarah Emerson, the disconcerting nature of a hidden subject is projected onto a landscape, perhaps even projected by that landscape. As the painting’s title suggests, Sweet Heebeegeebees (2013) pictures almost cartoonish yet nefarious scenery. Heads peer out at the viewer, some appearing to be skulls, other leering, eyeballs intact. Not fully formed, the concealed faces are perhaps paranoid visions, sprouting from the landscape like mushrooms and reflecting the nebulous unease found in much of Emerson’s work.

Hints at a subject are much more subtle in the contributions of Trenton Doyle Hancock. Though widely known for his highly figurative paintings and drawings, the Houston artist here presents four prints that are entirely text based. Titled Wow That’s Mean (2008), the black on black etchings continuously repeat the title of the suite in neat left-to-right lines gradually warping into swirls and spirals over the course of the four prints. The relentless reiteration of the phrase produces a visual sort of semantic satiation. Initially relating to Hancock’s saga of the Vegans and Mounds, the exclamation is repeated to the extent that the words lose their narrative meaning and become basic pictorial elements, not so much letters and words as complex mark-making. The prints progressively roil into a dark abstraction with any impressions of figures bubbling up for no longer than a moment.

Whereas Hancock’s suite of prints are subdued in narrative, an installation by Langdon Graves is replete with it. A corner of the gallery is arranged with four individual works that create a scene of melodrama through a lens of digital age iconography. Scarlatina (2014) and Scuttlebutt (2014) are built of symbols in the aesthetic style of wingdings or traffic signage and create a setting that seems intended to be read like a sign. Scarlatina (a term for scarlet fever) efficiently conveys, using hand-shaped and circular slips of vinyl, a glove draped over a towel rack and dripping with blood. Scuttlebutt, a yellow wallpaper that serves as a backdrop, is dotted with similar symbolism—a hand with the tip of the forefinger cut off, syringes, medical scissors, an eye and lashes, needle and thread. The pictographic nature of the installation is wonderfully contrasted by two of Graves’s drawings on an adjacent wall.

Hung in frames the same doctor’s-office-pink as the towel rack in Scarlatina, the graphite and pastel drawings are faithfully rendered as if pages from a taxonomy or medical text book. Ascelepius (2013) pictures what seems to be a dental or surgical tool intertwined with the sprig of a plant. The drawing and its title recall the so-named ancient Greek god of medicine and particularly his snake-coiled staff, which still is a symbol associated with healing. Red Over Red (2013) provides a cross section and a profile of a human eye—one looking out at the viewer, the other looking left at Ascelpius, Scarlatina, and Scuttlebutt. Looking on Graves’s four pieces as a whole, the relatable angst that accompanies the losing battle of a body and its upkeep hangs like ghost, invisible yet heavy. Her installation may demonstrate best the exhibition’s central theme of a visually omitted figure still haunting an artwork.

The underlying concept of “Darkness Invisible” is very specific, yet it avoids being a ham-fisted, overanalysis of some minutiae of contemporary art presented in boringly homogenous examples. Instead, the exhibition offers works that share a small yet fascinating intersection of interest, each thankfully pointing outward to yet larger concerns.

“Darkness Invisible” is on view at Tempus Projects in Tampa, Florida, through May 1.

Danny Olda is an art critic and editor based in Tampa, Florida