The seventeen artworks comprising Bed, the group exhibition on view at Marcia Wood Gallery, loosely reflect something we all know. Despite its overt familiarity, the word “bed” is remarkable in its multifariousness: it’s a piece of furniture, it’s a spatial zone (“a bed of flowers,” “a riverbed”), it denotes sex and sleep (“He went to bed with Aaron ;” “I read before bed last night”). While the paintings and drawings in Bed individually explore the term’s manifold meanings, altogether they don’t prompt reconsideration of the word bedso much as two-dimensional representation itself. The broad, quotidian theme allows for the striking juxtaposition of widely disparate styles in two common mediums that have long lost any unified stylistic trajectory.

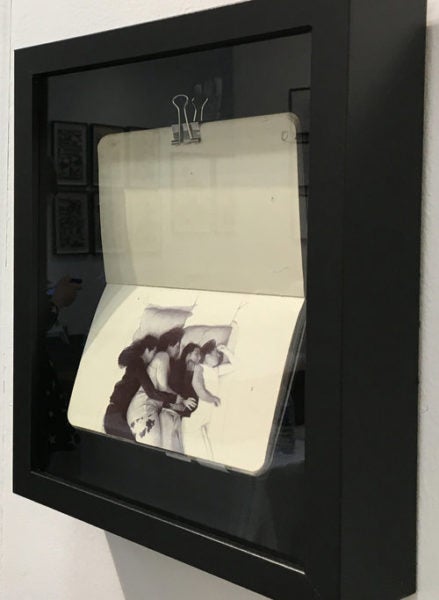

Two pen-on-paper drawings by Nicolas Sanchez investigate the intimate, subdued registers of the bed. Sanchez’s depiction of four women lying snugly atop a mattress, like close friends taking an afternoon nap in the wake of a lively morning, suggests the hushed, private aura of a diary—partially attributable to the drawing being displayed in the very notebook in which it was made, titled Sketchbook from artist’s commute. Right beside it, Abuelita Blanca generates a similar atmosphere, not merely because the subject is the artist’s grandmother, but because of the soft, unshaded black lines (reminiscent of those found in Ellsworth Kelly’s plant drawings) that form the bedroom and furniture it contains.

Sensuous realms of rest are conjured up by Sarah Faux’s Blush and Heavy Bloom, which simultaneously operate as landscapes, portraits, and abstractions. Lush colors of chlorophyll green, sunflower yellow, and rose pink initially seem to form non-objective swathes of color, like those found in Helen Frankenthaler paintings. Then, in these dabs and patches of paint, flora. Some dashes of green manifest as leaves; two patches of red represent, perhaps, tulip petals. Then, after reconsideration, the green leaf is actually an eyelash; the tulip petals are shapely lips. Faux’s works are flowerbeds in which people sleep and dream.

Kate Javen’s oil painting of a horse lying down likewise suggests a dreamscape, but a more meditative, melancholic one. Javen’s painting method is somewhat inverted. She first applies a thick quantity of dark paint, then removes it progressively to reveal the figure beneath, rendered in warm sepia tones. Javen’s horse is realistically defined, but its back blurs wistfully away, as if reflected in water. Often, Javen’s animal paintings symbolically depict figures in American history she considers particularly altruistic, such as the labor activist Oscar Neebe. While such gestures are good willed, they are objectionable in their resting upon the kinds of inherited, anthropomorphic notions of animal character that tell us owls are wise, foxes are sly, lions are noble—notions that reduce our understanding of the non-human. Javen’s painting in Bed, however, is untitled. It avoids anthropomorphizing entanglements, and enables the horse to signify itself.

The two paintings of Haitian-born Didier Williams both feature black figures set against cosmic fields of acidic, multi-textured color—the backdrops of strange dreams or nightmares. Williams’s figures are covered with hundreds of warbling eyes, like those covering Argus Panoptes, the many-eyed giant of Greek mythology. Rather than simply alluding to mythological narratives in the vein of so many paintings past, William’s eye-covered figures may be seen as visual dramatizations of the compulsory alertness, the justified, eyes-everywhere paranoia required of people of color in a society structurally opposed to their being. With this fraught mood in mind, Williams’s works nonetheless urge resistance and strength. One is titled Kenbe la, pa lage li, which roughly translates from Haitian Creole as, “Hang in there, don’t let go.”

Cuban-American artist Ariel Cabrera Montejo’s painting Wet Campaign presents the most striking visual effects in the exhibition through the overplayed idiom of impressionism. Montejo employs established impressionist techniques (broken color, opaque surface, short, thick brush strokes) to render historical scenes from late nineteenth-century Cuban history. Using this familiar method to depict historical subject-matter temporarily fools one into perceiving Montejo’s paintings as belongingto the period they depict. This impression, however, is quickly dispelled upon closer inspection of the painting’s compositional scheme. A man in the center of Wet Campaign photographs a river and the buildings along its shore. Various figures—a woman garbed in the corset of burlesque theater, a shirtless child, a neatly-dressed young man—fly towards him, striving to touch him. The theatrical attire of the woman and the weightlessness of the figures imply a scene in a theater, which is only reinforced by images of the walls and windows of a building folding away around the photographer, as though painted on a curtain. But the bubbles emerging from the mouths of some figures and the rippling lines of color at the top inch of the canvas suggest an underwater setting, that people are not flying but swimming towards the photographer. Where are we? Underwater? In a theater? Inside a collage of painted photographs? Montejo’s innovative formal scheme allows for members of multiple social strata from the Cuban Interwar Period—the solider, the burlesque performer—to coexist on a single, fantastical surface that defies physical laws and neat explanations.

Bed could just as well have been titled Dreams, as it contains a sequence of distinct visions that—despite their personal, deeply interior nature—implicate and reflect the broader world in which each artist dwells.

Bed was curated by David Humphrey and Kate Javens and is on view at Marcia Wood Gallery through June 1.