“Outliers and American Vanguard Art”—from the title, it is not immediately clear that this exhibition reconsiders art often referred to as outsider, visionary, or folk, in order to examine its relationship to the development of modern art in America. Curator Lynne Cooke chose the term “outlier” to counter the dismissive or limiting connotations that previous descriptors have taken on. It also stakes out a theoretical position. “Outlier” suggests that an artist’s distance from centers of institutional power can create space for different goals or values. The exhibition debuted at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., this spring, and opens on June 24 at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta, a museum known for its strong holdings in self-taught artists from the South. Comprising some 250 works — with slight variations between the venues — the show opens up the definition of American art, from the beginning of modernism to today, and challenges familiar notions of what modernism can look like.

“Outliers” charts the separation and intermingling of vernacular and fine art forms over time, complicating the domination, and definition, of American modernism. Among the earliest works in the show are anonymous 18th-century still lifes, which the National Gallery displayed alongside postwar ceramic figurines, faux naif landscapes, and modernist images of saints. In another example, an intricate tabletop tableaux carved in wood by José Dolores López (Adam and Eve and the Serpent, c. 1930), a craftsman in New Mexico, competed for attention with New York socialite Florine Stettheimer’s patterned and luminous portrait Father Hoff (1928). While stylistically and materially opposite, both works engage with figuration and Christian representation, ensuring that neither fit easily into the accepted narrative of American modernism.

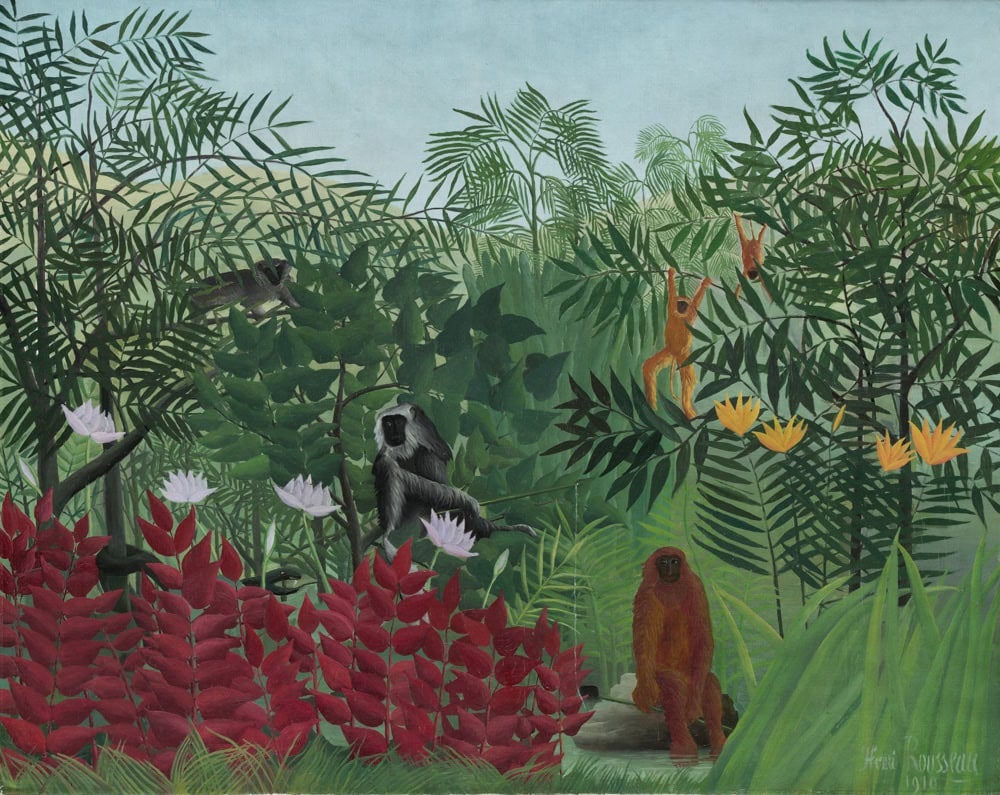

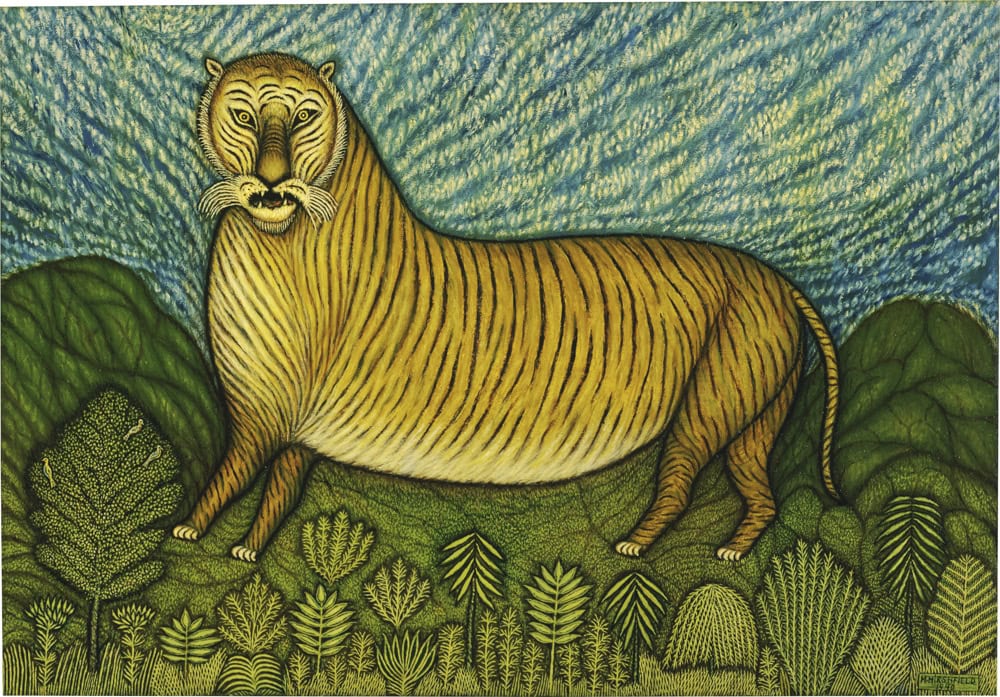

The earliest section of Outliers focuses on work made between the 1920s and ’40s, a time when self-taught artists were not banished to the outskirts of the establishment. Henri Rousseau is the best-known example; he retired as a municipal inspector in France at age 49 to create flat, polished paintings of people and animals in verdant natural settings, achieving recognition during his lifetime. His works were collected by the Museum of Modern Art, where they were displayed, notably, in a gallery that the first director of MOMA, Alfred H. Barr, reserved for “modern primitives.” Barr considered the work of modern primitives, or self-taught artists, an important influence on the mainstream art being made at the time. Other institutions also exhibited “visionary” or “primitive” artists regularly in the 1930s and ’40s. Landscapes and portraits by Rousseau and others in the exhibition are concerned with figuration, fidelity to nature, precise rendering, and decorative all-over patterning, running counter to the idea of modern art as a progression toward abstraction. The fantastic animal faces on view deserve an essay of their own. Morris Hirschfield’s Tiger (1940), for example, powerfully fills the composition with an almost Pointillist precision and radiating textures. Negative reactions to the Hirschfield’s work was allegedly a reason that MOMA’s adventurous first director was dismissed from his position in 1943.

One can read Barr’s dismissal as a symbolic end to a looser conception of modern art—but not before he mounted exhibitions of works by artists no longer considered part of the modernist tradition. An exhibition by Tennessee tombstone cutter and sculptor William Edmondson at MOMA in 1937 was the museum’s first solo show of an African-American artist as well as its first of a self-taught artist. Several of his stone sculptures are included in “Outliers.” Similarly, a 1938 MOMA traveling exhibition, “Masters of Popular Painting: Modern Primitives of Europe and America,” catalyzed Horace Pippin’s career eight years before his death, leading institutions such as the Philadelphia Museum of Art and the Whitney Museum of American Art to collect his work. Paintings by Pippin are a highlight of this exhibition, with their careful color modulation and their racialized version of American history as seen first-hand by this World War I veteran. If “Outliers” ended here, it would be an impressive historical exhibition that raises the question of why such powerful works of art are so rarely exhibited and discussed in modernist contexts.

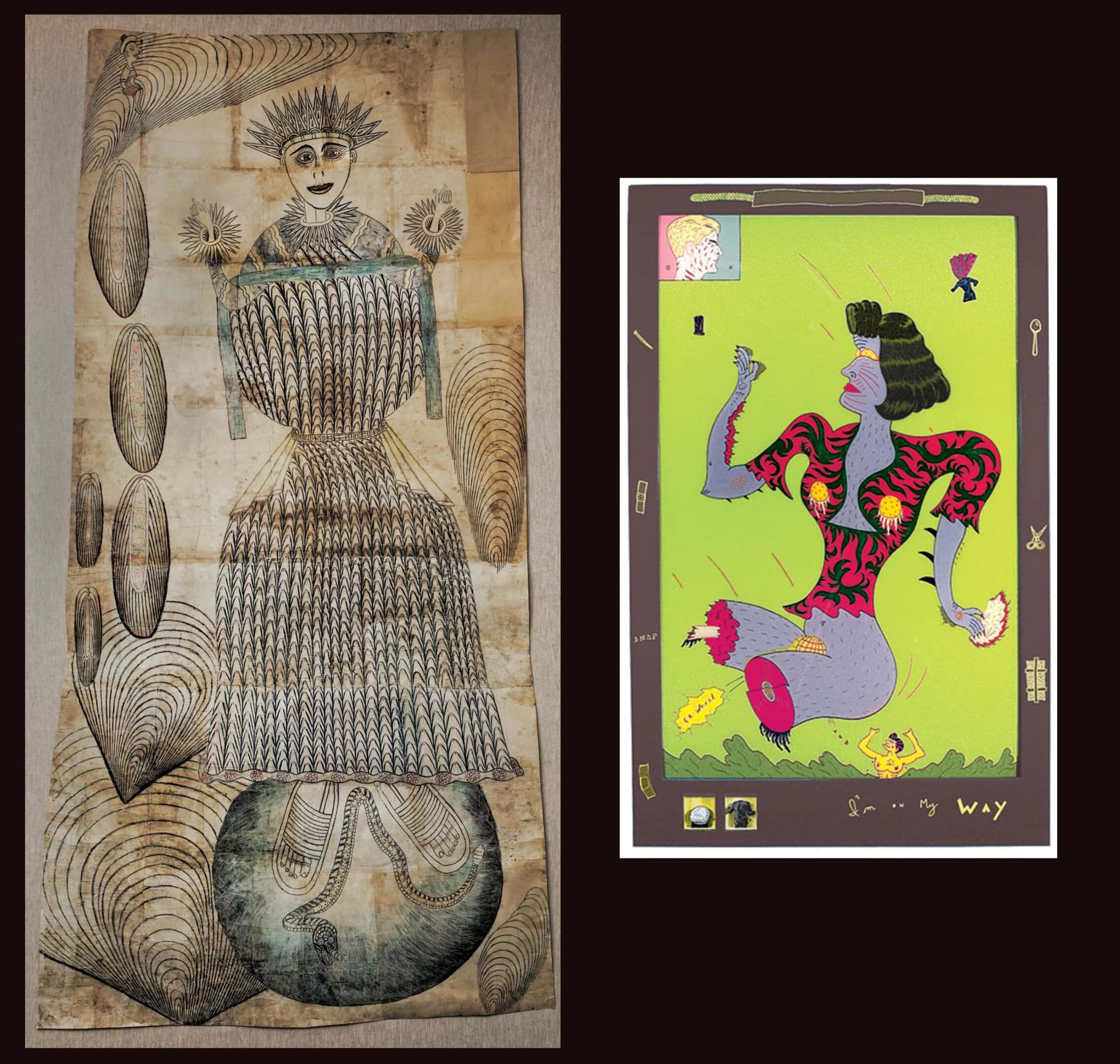

By the 1960s, the establishment definition of modern art had narrowed, and work by self-taught artists was considered to have no standard value in common with modern art. “Outliers” reconsiders the 1960s, beginning with wooden surrealist objects of impeccable craftsmanship by H.C. Westermann, a graduate of the Art Institute of Chicago, that are displayed alongside distinctive ink landscapes by the self-taught Joseph E. Yoakum, and graphite drawings of intricate symbolic narratives by Martín Ramírez, a Mexican citizen arrested in California and institutionalized there as schizophrenic for most of his life. According to Cooke’s conception, outliers develop work outside of mainstream tendencies but not in isolation from them; trained and self-taught artists often were in dialogue with each other. Chicago Imagists Jim Nutt and Gladys Nilsson, also on view in this section, championed the work of Yoakum when they met him in his retirement, and brought it into art world discourse. A prime example of such artistic championing occurs with the intimate abstract paintings and documentation of esoteric hermaphroditic theory by self-taught artist Forrest Bess (1911-1977), which were first exhibited together by contemporary sculptor Robert Gober as his contribution to the 2012 Whitney Biennial.

Works by Southern artists such as Jesse Howard, Howard Finster, Edgar Tollson, Elijah Pierce, Sister Gertrude Morgan, and David Butler converse in their use of unmodulated color, text and scrap materials, lack of perspectival depth, and the appropriation of vernacular tropes and Christian traditions. “Outliers” presents contemporaneous assemblages by California art world figures Betye Saar and Bruce Conner, who also pull from vernacular culture. Certainly, the works look and feel similar. I was struck by the reoccuring presence of the black body. Many artists represented race relations in the United States, from the historical scene of the death of militant abolitionist John Brown (Horace Pippin, John Brown Going to His Hanging, 1942) to flat cutouts of decontextualized violence (Steve Ashby, Untitled (Hunter and Victim), n.d.) to linking stereotypes of minstrels and watermelons to lynchings (Betye Saar, Sambo’s Banjo, 1971–72.) This is a necessary history in the story of modern American art.

Much of the work by the Southern self-taught artists has an overt Christian message. Sister Gertrude Morgan and Howard Finster used art as an evangelical tool—hand lettering Christian messages on any surface they could find. For both artists, commodifying their art was an unproblematic way to spread the word of God. Morgan sold hers from a revival tent outside New Orleans, while Finster marketed his from “Paradise Garden,” his elaborate installation and home in north Georgia. The Christian ideology on view does not reconcile easily with the modernist art-for-art’s sake doctrine, which holds that art should only be valued on aesthetic grounds rather than on social, ethical, or political concerns. And that, perhaps, is the primary reason that these works have been excised from the story of American modernism.

The most recent works in “Outliers,” made from the 1990s to the present, bring together the most predictable and the most surprising curatorial choices of the exhibition. Finally, we see the quilts of Gee’s Bend, a corner of rural Alabama made famous by a 2002 travelling exhibition that gave a high-art treatment to the output of the inventive quilting circle. Quilts have been shown at American fine art museums since the 1960s, successfully convincing appreciative audiences of the ways that this traditional craft anticipated modernt abstract painting. In “Outliers,” contemporary artists such as Alan Shields and Howardena Pindell riff on the feminine and the decorative in large hanging squares that formally approximate the traditional quilts on view.

Bright textiles and everyday objects create a dialogue about accumulation and material in recent sculptures by Judith Scott, Nancy Shaver, and Jessica Stockholder. Shaver and Stockholder are both accomplished, trained artists whose works circulate in galleries and museums. Scott came to artmaking later in life, having been sent to a state institution in Columbus, Ohio, at age 7 with Down syndrome and undiagnosed deafness. After 35 years of separation, Scott’s twin sister arranged for her release, and the pair relocated to California, where Scott began attending workshops at Oakland’s Creative Growth Art Center in 1987, and then worked prolifically until her death in 2005. Her dense cocoons of wrapped and knotted yarn surrounding common objects was the subject of a solo exhibition at the Brooklyn Museum in 2014-15. Presenting the works of these three artists together baldly calls into question the distinctions we make between trained and self-taught, outlier and mainstream.

The contemporary section of “Outliers” also includes a disjointed display of strong work by Robert Gober/Forrest Bess, Henry Darger, Noah Purifoy, and Matt Mullican though it is hard to find the conceptual thread that links them. Significant shifts in curatorial focus do not have the space to be fleshed out, as with James Benning’s video about Thoreau and Ted Kaczynski, which takes “outliers” as subject matter rather than a position to work from. Groups of works revolving around the female body and the Pictures generation, interesting in themselves, are similarly unclear in the context of this exhibition.

Regardless, “Outliers” successfully offers myriad new ways to unravel the modernist canon, opening up rich possibilities for a new understanding of American modern art.

“Outliers and American Vanguard Art” debuted at the National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., January 28–May 13, 2018. It is on view at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta through September 30, 2018, and then travels to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, November 18, 2018-March 17, 2019.