Visitors to the CDC Sencer Museum’s exhibition “EBOLA: People + Public Health + Political Will” will and should be overwhelmed. Throughout, there is an overarching and engaging narrative that vividly presents the epidemic’s complexities and chronicles CDC involvement. The exhibition pays tribute to all the players in this tragic and ultimately heroic drama: those who suffered, died, and survived the historic West Africa Ebola epidemic of 2014-16; the impacted families, communities and nations; the volunteers, health workers, staffs of numerous local and global agencies; and the governments who facilitated their work. The section devoted to public health encompasses an impressively detailed, fully faceted presentation on detecting the virus, treating its victims, checking its rapid spread, and educating various publics. The final section illustrates challenges of eliciting action from those in power, from local community leaders to heads of state, government agencies, international institutions such as the World Heath Organization and United Nations, and humanitarian agencies like the CDC Foundation.

The museum’s curator, Louise Shaw, and staff were aware from the early weeks of CDC involvement with the rapidly unfolding epidemic that the museum needed to document CDC’s participation, and that they were in a truly unique position to begin gathering and archiving materials to tell the story as fully as possible. This is nothing like “salvage archaeology,” where, out of necessity, excavators cut methodological corners and best practices as they work quickly to find and collect materials before a historical site is forever destroyed. In striking contrast, the CDC museum’s “rapid response archiving” captured history as it happens. On-the-ground staff in West Africa collected items ranging from the obviously historic to the simply mundane, resulting in an array of items that attest to the urgency of CDC operations in often surprising and always affecting ways.

The exhibit opens with “A look at the history of Ebola in West Africa, 2014-2016, and how CDC, global partners, governments, organizations, and individuals came together to stop an epidemic,” as the wall text reads. Behind the text looms a faint but gigantic image of the microscopic Ebolavirus, a glimpse of the biological creature behind all this havoc—the virus that killed 11,325 out of nearly 30,000 people with suspected, probable, and confirmed instances of infection. Prefacing the West African outbreak , a time line chronicles historic outbreaks of Ebolavirus beginning in 1976 in the Sudan. The first recognized outbreak of Ebola followed in the 1990s in Uganda, Zaire, and Republic of Congo. An adjacent graph comparing totals of survivals and deaths is indeed sobering.

A timeline of the West Africa outbreak is amply illustrated with photographs and other images that present successive historic moments and stages of public health intervention. Ebola victims dominate the timeline in a massive jagged red line that leaps from the floor, peaks in October 2014 near the top of the wall display, and then rapidly descends as deaths diminish, trailing off to a triumphant null. The jagged red line’s width expands and narrows with the numbers of infections—an image every bit as ominous as the gigantic Ebolavirus that greeted us at the entrance.

A video projection of the May 2015 PBS Frontline report “Outbreak: Why Wasn’t the Ebola Outbreak Stopped Before It Was Too Late?” speaks directly to political, historical, and everyday realities that set the stage on which the tragedy unfolded. The report serves equally as the exhibit’s preface in laying out the critical dilemmas that framed the epidemic and as its conclusion in equipping the visitor to see the exhibit as an epic cautionary tale.

Beyond the introductory didactics, titles and narratives introduce topical displays, and reading is a must for those unacquainted with public health or the epidemic’s history. The exhibition is rather text-dense and of course it must be. There’s much to be explained. Most artifacts require descriptive context, and together they relate a compelling story composed of countless individual narratives.

Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone—ground zero of the epidemic—are among the poorest nations in the world. Urban areas are crowded with migrants from the countryside. Intense mining and deforestation have pushed many farmers into poverty. Liberia and Sierra Leone are still recovering from long civil wars. Throughout West Africa, weak public health infrastructures were ill-equipped when, on December 6, 2013, near the shared borders of Guinea, Sierra Leone and Liberia, a two-year old boy in rural Guinea developed a fever, diarrhea, vomiting and died within days. Ten days later Medecins Sans Frontieres (Doctors Without Borders), the only international health agency operating in the region at the time, opened an isolation ward and called out to the international community for urgent action. The now historic Ebola epidemic had begun, was quickly advancing, and ominously no longer a rural phenomenon.

On March 18, 2014, Guinean health officials announced that a fever “which strikes like lightening” had infected at least 35 individuals and killed over 23. A week later in Lyon, the French Institute Pasteur suggested it was Ebola. On March 30, the first case in Liberia was confirmed, and the next day CDC sent a team of six there to collect data, meet with partners, and offer risk consultation. The following day Sierra Leone confirmed cases and in June closed its borders with Liberia and Guinea, and closed schools in a further effort to stop the spread.

Months later, on August 8, after continuous urging, the Director of the World Health Organization declared a “Public Health Emergency of International Concern,” triggering the international deployment of supplies, equipment, and staff. By mid-August Ebola’s exponential spread increased alarm. On August 29, the Presidents of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone wrote to UN General-Secretary Ki-moon urging a UN resolution. In a large photo of the UN Security Council meeting, we see physician’s assistant and MSF first responder Jackson K.P. Niamah on a massive screen speaking via video link from Liberia:

“I feel the future of my country is hanging in the balance. We do not have the capacity to respond to this crisis on our own. If the international community does not stand up, we will be wiped out. We need your help. We need it now.”

His plea communicated the region-wide urgency and ambient desperation, effectively illustrating why the phrase “Political Will” belongs in the exhibition’s title. It’s also clear why wall texts, photographs, and video, as the primary means of public communication, are the appropriate tools for conveying political will. As easily inured and sadly accustomed we are to world leaders and supra-national organizations acting in ways that hinder action and resolution, it is heartening to see how, eventually, those with the power to help rose to the occasion.

The CDC’s immediate on-the-ground goal was identifying, isolating and caring for the ill. The variety of ways this was achieved forms the heart of this exhibition. Ebola is highly contagious, spread by mere touch—with a sick person, with body fluids or the dead—and symptoms may not present for two weeks. Consequently, isolation and tracking contacts—and the contact’s contacts for as many “generations” as possible—are essential for containing and eliminating the virus. At this point, public health clearly becomes a social as well as medical science, which the section titled “Educating While Investigating” presents with a wide variety of items, such as a deeply affecting diagram sketched on the inside of a used manila folder. Referred to as cluster tracing, it maps a patient’s social contacts and social relationships, each identified individual needing to be visited repeatedly for several weeks to ensure symptoms haven’t presented. A large whiteboard—remarkably not erased!—displays a larger, more complex cluster map from Sierra Leone, very effectively collapsing time and space as we stand looking at the whiteboard just as the health workers did.

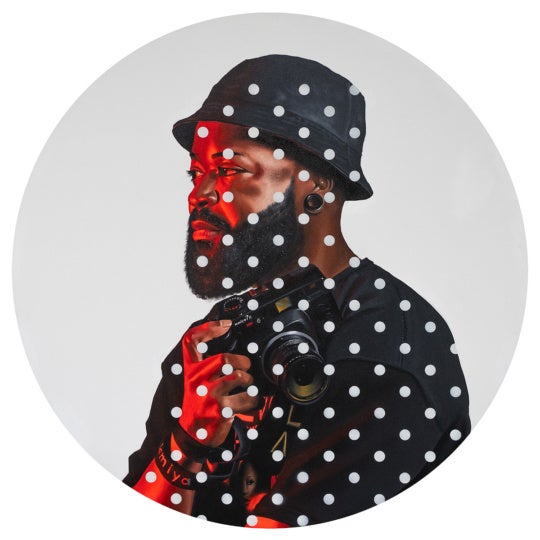

An ambulance demonstration in Sierra Leone. Many people had never seen or were suspicious of ambulances. Photo: World Health Organization.

Any public health effort shoots itself in the foot that dismisses a community’s cultural understandings, practices and influential individuals. For example, low-tech rural Emergency Treatment Units designed to hold and treat patients while awaiting lab results were themselves held in suspicion by the community. Family members, unable to visit, occasionally even “rescued” patients. A photograph shows a woman visiting a redesigned Liberian ETU unit, its once solid wall replaced by a waist high partitions allowing visitors to come near, see, and converse with sick kin. Ambulances were often feared; many people had never seen one, or had seen people taken away in them never to return. It was rumored that those taken away were purposefully infected while in the ambulance itself. A staged public demonstration in Sierra Leone against ambulances is seen in another photo.

Many burial practices were countervailed by public health procedures and often required modifications on both sides. A section labeled “Faith, Culture, and Tradition” contains particularly affecting objects: three gratefully unused wooden white crosses from Liberia, and a shovel and pick-ax from the Liberian National Cemetery. The pick-ax is particularly beautiful, its handle fashioned from a branch with little alteration except where it precariously meets the metal. In a photograph of a funeral, a minister stands between a swaddled body lying on the ground and mourners, documenting a vital change in traditional burial practices that often involved touching the body of the dead. Also on display is a staff, drum and hat presented by traditional healers to Ebola health educators they worked with. The gifts serve as significant evidence of their intimate cooperation. A Koran and a Bible opened to highlighted passages about disease prevention also serve to minimize contrasts between religious practice and medical knowledge.

This exhibition is replete with objects and media that bear witness to staggering complexities, and visitors interested in communication and educational features of public health will find varied examples. Training materials and community education efforts from local to national levels are illustrated in many media and several languages, some produced by CDC’s Division of Creative Services, such as “Breaking the Ebola Chain of Transmission,” a storyboard with artwork by Solomon, a West African artist. Hand-painted banners from Liberia reveal important grass-roots educational efforts. There are also storyboards, posters, schoolbooks, television clips, playing cards and other popular media. A sign “Drinking Chlorine can make you sick or kill you” alerts the visitor to the necessary breadth of public messaging. A large poster and accompanying training video illustrate new guidelines for protective gear, including correct methods of donning and doffing the gowns. Anyone with a particular interest in diagrams and other info graphics will have a lot to enjoy.

The array of technologies on display fascinates: an infrared thermometer that registers body temperature without physical contact accompanied by an illustrative photo, a Sierra Leone “Question Box Phone” available in public spaces, a wireless doorbell set up in a Sierra Leone emergency lab, and an amazing nucleic acid extractor used in a CDC lab that processed 96 suspected Ebola samples every 30 minutes. This and much more remind us that technologies from the simplest to most advanced occupied essential roles in halting the epidemic.

There are lessons to be learned. Nigeria deftly avoided their own potential Ebola epidemic by acting swiftly when, on July 20, 2014, Liberian-American Patrick Sawyer ignored medical officials’ advice and flew from Monrovia to Lagos, where he collapsed in the airport and died five days later. Nigeria’s strong public health infrastructure and decisive government action contained potentially vast devastation with only 23 individuals sickened and 9 deaths.

In the United States during the same week, two health care workers who had worked with Ebola patients returned from West Africa died. Later, an infected Liberian traveller arrived in Dallas, again prompting heightened public concern and U.S. media attention. In addition to its West Africa operations, CDC handled domestic issues, such as recommending procedures and efforts to counter an epidemic of fear and rumor. The quarantine of returning health care workers became an issue. Particular attention is given to the case of nurse Kaci Hickox, who volunteered to treat Ebola patients in Sierra Leone with Medecins Sans Frontieres. Upon returning to the U.S., she was quarantined in New Jersey for four days before a settlement allowed her to continue the quarantine in her home in Maine., which is seen in a photograph surrounded by media cameras and reporters. She later filed suit against Governor Chris Christie and New Jersey health officials. A succinct, informative discussion of lessons learned is presented in a video interview of CDC Director Thomas Frieden, who passionately argues that strengthened health infrastructures is the best preparation for future challenges like Ebola.

Since it covers a single multiyear event, by far the largest Ebola epidemic yet, and because the virus was contained by unprecedented international intervention, the daunting subject defies summation in a single exhibition. In just a few years, the epidemic has generated countless forms of media attention: a simple Amazon search returned over 3,000 books. Yet, the CDC Sencer Museum managed to present a coherent and thorough exhibition. Most noteworthy is the wealth of physical artifacts that served their functions in West Africa and now serve to tell a profound story.

Before leaving the exhibit, I recommend watching the music video “Bye Bye Ebola,” a jubilant song composed to celebrate the end of Ebola in Sierra Leone. The succession of dancing participants—nurses, policemen, motorcycle deliverymen, doctors, community leaders, and especially joyful children finally back in school—is an uplifting counterpoint to the virus’ alternative outcome.

“EBOLA: People + Public Health + Political Will” is on view at the CDC Sencer Museum through May 25.

Daryl White is professor emeritus of anthropology at Spelman College.