It’s arguable that our art historical moment will be defined by revisionism. Though this impulse isn’t new, a conglomeration of exhibitions over the past decade have rightfully sought to reassess the legacies of artists—often women and people of color—whose practices have been overlooked by museums or excluded from the canon of artworks taught in universities and textbooks. “Against the Grain,” a small exhibition of Mildred Thompson’s little-known Wood Pictures at the New Orleans Museum of Art, acts on this corrective impulse while raising questions about how we integrate figures into the grand narrative of art history.

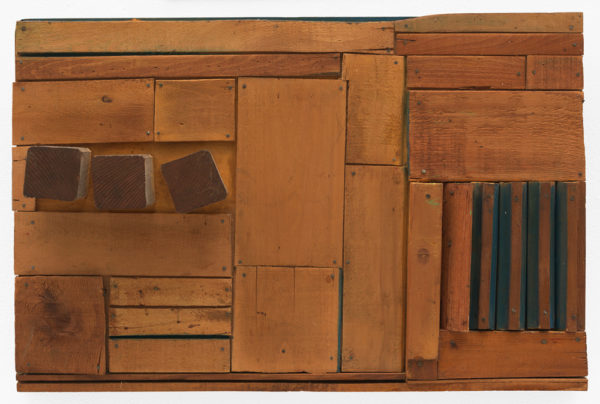

A few years ago, curator Katie Pfohl learned of Thompson while researching works for possible acquisition into the museum’s collection. NOMA purchased three of Thompson’s rectangular wall-hung assemblages, which are comprised of pieces of found wood cut and carefully arranged into cryptic patterns. Though the works were briefly on view last year during a collection show at NOMA, “Against the Grain” contextualizes them with a selection of other Wood Pictures and a related series of prints, a jaunty take on the rigorous rectilinear forms of Piet Mondrian and other De Stijl artists.

Many of Thompson’s Wood Pictures are comprised of a plane of similarly colored, raw, parallel slats that look like floorboards, interrupted by smaller pieces joined at an angle or painted different colors. In one work from 1971–72, a jagged orange line nestles around a square created from dark brown molding, the visual centerpiece of the composition. Another smaller artwork from 1967 appears almost as a puzzle, with knoblike protrusions seemingly waiting to be turned to unlock some secret within. This mysterious quality feels suggestive of a game in which Thompson challenges us to consider each component’s history while also reckoning with the inscrutability of the work’s very objecthood.

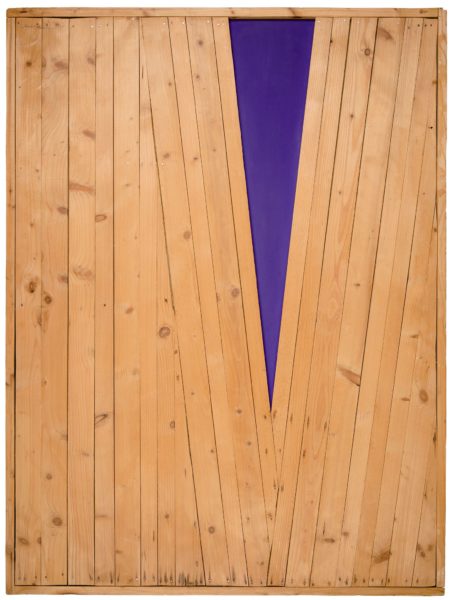

The highlight of the show is a Wood Picture from 1972—which entered NOMA’s collection through that 2016 purchase—in which a sharp triangular cut-out at the top of the smooth field of boards reveals a shockingly purple surface underneath. Other Wood Pictures are less tidy, including two all-white works that incorporate clothespins and thin curved scraps resembling ribs. Taken together, these works evidence Thompson’s interest in both assemblage—exploring the relative meaning of her materials as they are clumped together—and in Minimalism, with its clean, orderly lines and matter-of-fact presence.

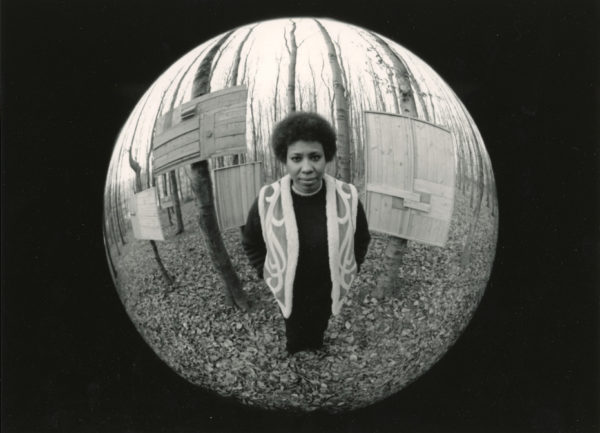

Thompson, who was born in Jacksonville, Florida, began making work in the 1950s. After attending Howard University and then moving to New York, Thompson began to feel constricted by the opportunities afforded to her in the United States. Despite an early acquisition of her work by the Museum of Modern Art, Thompson felt excluded from exhibitions at historically white institutions and limited by the dictates of representation within the Black Arts Movement. (Thompson once lamented artists at Howard telling her in the 1970s she was not a “Black artist” since “there is no trace of Africa in your work.”) Finding more artistic freedom in Europe, Thompson lived in Germany on and off for years before finally settling, in 1985, in Atlanta, where she taught at the Atlanta College of Art, Spelman College, and Morehouse College, and worked as associate editor of Art Papers.

It is only recently that Thompson, who died in 2003, has received significant attention in the United States. She was propelled into the spotlight by the monumental 2017 exhibition “Magnetic Fields: Expanding American Abstraction, 1960s to Today” at the Kemper Museum of Contemporary Art in Kansas City, Missouri. (The show took its name and catalogue cover art from a vibrant series of Thompson’s paintings from the 1990s.) Galerie Lelong & Co. in New York began representing the artist’s estate last year and opened a solo exhibition of her paintings this past February. In Europe, selections from both of the bodies of work on view in “Against the Grain” were shown in this year’s Berlin Biennale, curated by Gabi Ngcobo. And other recent exhibitions, including “Solidary and Solitary: The Joyner/Giuffrida Collection” at the Ogden Museum of Southern Art in New Orleans and “Out of Easy Reach,” curated by Allison M. Glenn at three venues across Chicago—both of which did not include Thompson’s work—signify larger interest in asserting the importance of women and artists of color working in abstraction.

Thompson’s works don’t fit easily into the story of art history. The Wood Pictures bring to mind, in their own ways, references as vast as Noah Purifoy, Louise Nevelson, and Ellsworth Kelly—and her later paintings find odd kinship with Sol Lewitt, Wassily Kandinsky, and Stuart Davis. But Thompson put forth something completely new, a mélange filtered through her own vision of the world. Ushering artists into a conventional canon prompts many questions, but most resonant here is the challenge of understanding artworks within the context of art history while not erasing the inexplicable aspects that distinguish them from those very narratives. Thompson’s works ask us to take them as they are, and that may be the best we can do.

Mildred Thompson: Against the Grain remains on view at the New Orleans Museum of Art in New Orleans, Louisiana, through March 31.