Gold, silver, and jewels decorated the covers of medieval illuminated manuscripts, communicating the preciousness of the text. Walking into “Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities,” on view through May 20 at the Spelman College Museum of Art, is like opening such as book. Behind the seductive surface of her well-known earlier works lies a rich interior. The works in “Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities” mark a shift in practice for the midcareer artist. Fans of Thomas’s rhinestone-encrusted paintings of black women in ’70s-style interiors will likely be attracted to her new approach as well. Her recent forays into video and installation address concepts that have always been at play in her work—gender, sexuality, and race—albeit with a directness that shakes off the glitz and goes straight for the jugular.

Singer Eartha Kitt’s plaintive “Angelitos Negros” permeates the dimly lit interior, rising above the din of video installations. Thomas’s video collage of the same name reworks the 1953 song in which Kitt contemplates the dearth of black angels appearing in Christian art of the Western tradition. Though working with video, repetition and pattern remain a hallmark of Thomas’s practice: she multiplies Kitt’s image, closes in on her eyes and lips as if to increase the pathos of the song. Thomas also integrates images of Kitt with contemporary women, including herself. Dressed like Kitt in black turtlenecks, they mimic her emotive gestures, extending Kitt’s presence like a chorus and suggesting the song’s continued relevance.

Plush pillows and ottomans arranged on patterns made of overlapping squares of carpet and laminate provide seating in front of Angelitos Negros and other videos, like islands of domestic space. The juxtaposed motifs of the cushions and tiles recall her earlier paintings; it’s like stepping into one of Thomas’s florid wallpapered interiors. Books by and about black women—Alice Walker, Toni Morrison, Zadie Smith, and more—anchor the corners of the carpets.

Do I Look Like a Lady? (Comedians and Singers) likewise relies on collage tactics. Two screens are broken into irregular, Mondrian-like grids. They rotate clips of black female celebrities as diverse as Josephine Baker, Whitney Houston, and Wanda Sykes, as if to remind us that comedy and entertainment is a space for revolutionary ideas. Quieter and more intimate, a series of Screen Tests—titled individually, like Screen Test: Angel or Screen Test: Theolanda—feature women staring into the camera with unwavering intensity. The black-and-white films, digital transfers of Super 8 film, overtly nod to Warhol’s famous Screen Tests of the 1960s. Bright swatches of painted color interrupt their near-religious austerity.

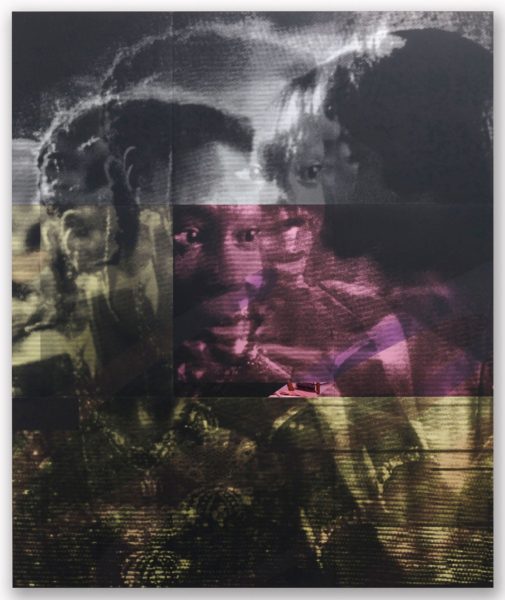

Shug Kisses Celie shows two superimposed portraits of Celie, the protagonist of Alice Walker’s 1982 book The Color Purple, as played by Whoopi Goldberg in Steven Spielberg’s 1985 film adaptation. Using silkscreen images of film stills, the work is printed on a mounted acrylic panel over 6 feet tall. Large pixels make up a pattern on the specular surfaces of gold and purple panels. Close to eye level, a trapezoid of shiny, blank purple mirror reflects the viewer’s eyes. It’s an intimate and romantic translation of the women’s kiss and Celie’s transformation from shrinking violet to happily emboldened woman with the aid of her lover, Shug Avery. The theme of black female empowerment, love, and community are the heart of the exhibition.

Though the traveling exhibition was organized by Colorado’s Aspen Art Museum, circuitous connections embedded in “Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities” subtly tie the artist to Spelman’s campus. Walker attended Spelman (as did a minor character in The Color Purple, Corrine, who graduated before becoming a missionary in Africa). In the book, Spelman appears as a beacon of positivity in a bleakly oppressive and racist early 20th-century Georgia. Spelman influenced Walker, who in turn inspired Thomas and myriad other women.

Fully fleshing out this connection is the small exhibition “tête-à-tête,” curated by Thomas and featuring works from the permanent collection of Spelman College including Lauren Kelly’s Big Gurl (2006), Xaviera Simmons’s And/Or Mouse (2016), Howardena Pindell’s Free, White, and 21 (1980), and Derrick Adams’s My Jesus Place (2014). Perhaps the most compelling and historically significant inclusion is Pindell’s video, in which the artist plays two parts: herself, a black woman describing instances of racial discrimination in her life, and the titular free, white, and 21-year-old woman who disbelieves and admonishes her. Pindell eventually wraps her face in white gauze, eradicating her identity and whitewashing her experience. Pindell draws attention to the dearth of black voices in second-wave feminism; thus, her work fits into the rubric of womanism, a corrective to white, middle-class feminism, that was inspired by a 1983 essay by Walker (In Search of our Mother’s Gardens: Womanist Prose). Thomas’s inclusion of her poignant video this exhibition situates her as one of the many muses and mentors that paved the way for Thomas’s generation.

As is the case with Walker’s The Color Purple, Thomas’s exhibition celebrates a community of women who flourish together through mutual support. Yet despite her praise of other women, one the most powerful works in the exhibition is the contemplative Me as Muse. A multimedia video installation less than five minutes long, Me as Muse is a grid of screens that fluctuate between pixelated patterns, historical images, and a nude, reclining self-portrait of Thomas. A voiceover of Eartha Kitt describing her troubled childhood and disappointing relationships with men (“man has always wanted to lay me down but never pick me up”) accompany the video and connect the self-reflexive work to the show’s larger themes. The ever-shifting series of images in Thomas’s dynamic video include many historical referents such as classicizing, white women of the French academic tradition and pictures of Sarah Baartman, so-called “Hottentot Venus,” a South African woman who was exhibited in Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Thomas’s own image meaningfully engages with—and perhaps rectifies—this harmful tradition.

Thomas slowly occupies the screen during the course of Me as Muse. Beginning with a peripheral foot on a single screen, her image eventually fills the grid of screens. Close-ups of her body alternate with full representations. At one instant, her head and torso is joined to a the hips and legs of a painting of a white reclining nude, suggesting inextricability. Most meaningful perhaps is Thomas’s claim as both artist and subject. While there’s a long tradition of Western male artists depicting nude women, there’s a shorter list of women who depict themselves this intimate and direct manner (such as German Expressionist Paula Modersohn-Becker, American modernist Florine Stettheimer, Mexican painter Frida Kahlo, or, more recently and most critically, American artist Lynda Benglis). It suggests a critical appropriation of the male gaze and a poignant embrace of body and sexuality.

If we take Manet’s Olympia (1863) as a critical-yet-still-problematic exemplar of the patriarchal tradition, we might imagine that Thomas reclaims the marginalized positions of both the recumbent white sex worker (ridiculed as corpse-like and revolting in contemporaneous criticism) and her black attendant (offensively disparaged by 19th-century critics as a “hideous Negress”). Ever mindful of art history’s exclusion of women like herself, Thomas’s image is under her control in Me as Muse. Works such as this one carry the lineage of the womanist tradition forward and answer the call of Eartha Kitt’s “Angelitos Negros”: “Paint me some Black angels now.”

“Mickalene Thomas: Mentors, Muses, and Celebrities” was organized by the Aspen Art Museum and is on view at the Spelman College Museum of Fine Art through May 20.

Rebecca Brantley teaches art history at Piedmont College. She is chair of exhibitions and programming at ATHICA: Athens Institute for Contemporary Art and was a participant in the inaugural cycle of BURNAWAY’s Art Writers Mentorship Program.