Comic books, Pez dispensers, holograms, and monuments. In Giant-Sized Annual: A Solo Exhibition in Two Parts, on view at Lump Gallery in Raleigh, North Carolina through August 31, artist Topher Lineberry fuses fragments of memory with speculative design, assembling a multiverse of regional folk traditions and pop culture ephemera. The title, drawn from comic book publishing convention, signals the show’s ambition: a thick, many-threaded gathering of past and future entanglements, told in two chapters, “Side One” and “Side Two.”

The show opens with “Statuemania!,” a gallery filled with drawings, photographs, collages, and sculptures that stage a conversation with Southern monuments and histories of world’s fairs and global exhibition culture. Here, Lineberry trades marble and bronze for glitter, rubber bands, costume jewelry, and cast-off toys. Depicted figures like Wonder Woman, Daniel Boone, and App State mascot Yosef the Mountaineer flicker between gravitas and kitsch. Several works nod to regional debates over public memory—including Confederate monuments—yet Lineberry avoids easy satire. Instead, they assemble a queer, speculative monumentality—prequel and sequel fused into what the artist calls “a queer space of becoming”—where new kinships can be imagined across cultural and temporal registers.

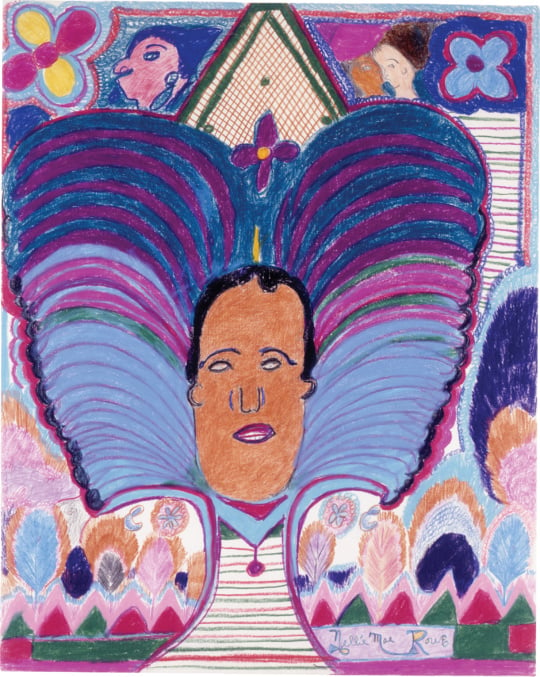

Lineberry’s familial and regional ties quietly structure the show without rendering it parochial. Raised in Greensboro with ancestral ties to Watauga County, the artist draws from Appalachian folk schools, regional archives, and the life and work of their grandmother, Helen Gaines Howerton Lineberry (1919–2012), an Asheville-based artist who created prolifically during the heyday of Black Mountain College. While not formally affiliated with the College, Helen’s adjacency to it echoes in her grandchild’s recursive, archive-aware approach. Lineberry’s aesthetic, too, shares this quality of adjacency, informed less by the work of celebrated Black Mountain College instructors like Josef Albers than by pop-leaning students whose lives intersected only briefly with the college, like Robert Rauschenberg and mail art founder Ray Johnson.

Black Mountain College is just one of many points of entry for this work. In Lineberry’s expansive matrix, the local meets the global. Intensely aware of Appalachia’s rootedness on stolen land, the work links the region’s folk schools to European precursors: Black Mountain to Bauhaus, Highlander and John C. Campbell to traditions in Denmark. Art institutions come under scrutiny for their complicity with settler-colonial projects of global influence in a series of “Pez Pavilion” sculptures and drawings like Study for Mickey Mouse Pavilion (2019). Each of these works replace symbols of corporate modernity with Crystal Palaces under erasure: burnt scaffolding, skeletal ruins, architectural models made of bits of Pez dispensers, deconstructions open to the outside. Lineberry’s Mickey Mouse Pavilion stands out here. Rendered in graphite and colored pencil on cut paper, the work forms a visual rhyme of sorts with a passage in Fredric Jameson’s Postmodernism, or The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (1991), where Jameson describes riding a capsule-shaped glass elevator along the exterior shell of LA’s Westin Bonaventure hotel. Pavilion and hotel appear for Lineberry and Jameson as postmodern restagings of modernity: Crystal Palace turned on its side and launched, like a rocket ship, from Disneyland out into hyperspace.

Where the term “folk” can too often in the work of other artists evoke only pastness and nostalgia, Lineberry’s works clock as-yet unrealized futures, whether through proposals for hologram monuments, or through prints like Solar Panel Conversion Therapy for Monument Base of Toppled Confederate Soldier Statue, Durham, NC (A Proposal to Redirect Power) (2017).

The show’s other half, “Memory X-Ware,” offers Lineberry’s most recent body of work. Named after the folk tradition of “memory ware,” vessels encrusted with keepsakes, this series collides Southern craft with the high-gloss aesthetics and mutant mythology of superhero comics. Pages from X-Men #1 (1991) are layered, crossed out, graffitied, and reconstructed into new formations. Pages become pulp. Collages and papier-mâché sculptures sprout from the ruins. The results feel both reverent and insurgent: a speculative Appalachian futurism staged with glue guns, patch concrete, and comic book lore.

The show’s crowning achievement is Nathanial Greene: A Revolution (2018-2025), a 42-second digital animation that loops endlessly on a screen between the two rooms, rotoscoping psychedelic bursts atop footage of a statue of Greene that stands at the center of a traffic circle in downtown Greensboro. If the show is an LP divided into a “Side One” and a “Side Two,” then Greene is the spindle around which the record spins. Rather than depict the monument’s toppling, Lineberry refashions it into a site of solar-powered potential. Monument becomes proposal.

This is perhaps what makes Giant-Sized Annual so resonant: its refusal of binaries. Pop and folk, nostalgia and futurity, kitsch and critique are entangled in a southeastern translation of rasquache splendor. The show recalls the aesthetics of altars and memory palaces: accumulative, relational, grounded in care.

For all its glitter and pop appeal, Giant-Sized Annual is ultimately about memory as practice: a way of reassembling what has been discarded or forgotten into new visions of the possible. The show edges insistently toward speculative ritual, inviting viewers to imagine new networks of relation, new memorials, new myths. Like a well-loved comic book, its pages are dog-eared, its stories cross-cut. But its heroes—regional folk artists, queer futurists, and grandmothers—remain gloriously alive here in the present.