![Safe House [door]](https://s1.burnaway.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/Safe-House-door-500x343.jpg)

“Mel Chin: Rematch” at the New Orleans Museum of Art through May 25, showcases the artist’s dynamic practice that has developed over 40 years. The works are installed as they are in many museum exhibitions. However, the wall labels here, often describing the pieces at length, are instrumental to understanding the multiple layers we find distilled down to the beautiful art forms on view. As socially engaged and conceptual practices have increased in number and study, curators, art historians, and participants have been charged with myriad challenges recording and presenting these projects for future examination; and while many objects here stand on their own, others become mere representations of actions, requiring further explanation. While “Rematch” demands a greater attention from the museum visitor, the works presented exemplify Chin’s ability to playfully and seductively educate and challenge viewers and participants, honoring the artist’s belief that knowledge as a powerful tool of change.

Organized chronologically, for the most part, the exhibition highlights the artist’s incredibly diverse career, from early land works to his more widely known conceptual and environmental practices—emphasizing “Rematch” curator Miranda Lash’s assertion of “mutability” as Chin’s “operating process.” Alongside photographs of Chin’s initial public art projects and sculptures, as well as early works drawing on his influences from Joseph Cornell and Marcel Duchamp, Extraction of Plenty from What Remains 1823– (1989) ignites Chin’s expansive dialogue around the United States’ international policy and human rights issues. Here, two columns measuring the same circumference of those in front of the White House are etched at the top with the signatures of presidents who signed their names on policies devastating to Central America. Starkly placed between them is a large, empty cornucopia created appropriately from Honduran mahogany, bananas, mud, coffee, and blood.

![1999 - KNOWMAD [installation view]](https://s1.burnaway.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/1999-KNOWMAD-installation-view-500x334.jpg)

Moving through large installations such as Operation of the Sun Through the Cult of the Hand (1987) and the 2006 sculpture Circumfessional Hymnal Sea (Portrait of Jacques Derrida)—these works exemplifying Chin’s grounding in theory, symbolism, philosophy, and mythology— dramatic, often trivial, conversations spill over from a small living room in the middle of the gallery. Here, visitors are invited to sit and watch clips of the 1990s television series “Melrose Place.” From 1995 to 1997, Chin worked with the GALA Committee, 120 artists and students in California and Georgia, to create works that quietly intervened in the TV show. They created objects, such as a quilt diagraming the molecular model of the RU-486 emergency contraception drug, that actors in “Melrose Place” used or that appeared as passive props. In the Name of Place used the viral tactics of commercial marketing to disguise direct references to social and political issues as props.

Close by, a tongue sticks out of a floating wall in a youthful gesture of distaste. On the opposite side of the wall, a large, solid black, and bulbous sculpture fills the surface and projects itself upward and outward. Shape of a Lie (2005) represents an inflating lie, as well as the attempt to stop it, which takes the form of a sharp dagger-like element piercing into the top of the sculpture like a needle to a balloon. The piece is a visceral demonstration of the construction and often-intertwined nature of truth and fiction, or as Chin describes, the “construction of truth” as “illusive.” The work is situated in the “Weapons” section of the exhibition, which includes Chin’s works that twist deathly objects and information into beautiful works and utilitarian tools. Ultimately, Chin’s practice has been dedicated to urging individuals to question what is believed to be “true.” Whether gracefully scrutinizing climate change, such as in the installation Decades of Paradise (1992), or cultural manipulation, as in the interactive videogame KNOWMAD (1999), Chin creates interesting and engaging spaces to educate the viewer.

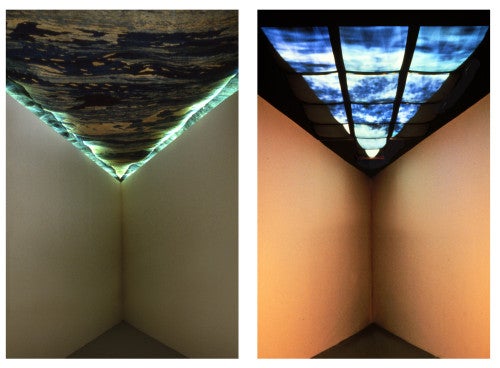

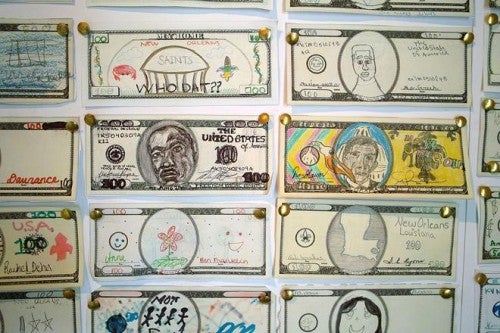

Chin’s works have taken on many forms of public engagement, but Operation Paydirt (2007-) is particularly well known for its ability to sustain an expanded dialogue due to successful distribution channels. In 2008, Chin opened the doors to the Safehouse in New Orleans’ St. Roch neighborhood. The house, characterized by a larger-than-life bank vault door, was the hub for Operation Paydirt / Fundred Dollar Bill Project and housed educational materials. The project revisits Chin’s Revival Field, stressing that early exposure to lead has strong links to learning disorders, as well as violent behavior and other health issues later in life—problems proliferating in New Orleans and Chin’s hometown of Houston. One by one, individuals color Fundred dollar bills, and in doing so raise awareness of these issues while contributing to a dollar-matching program that will be presented to the government to instate hyperaccumulation projects in affected cities..

Like many of the other works in the show, this project is represented in the exhibition through objects: large, bundled stacks of collected Fundred Dollar Bills, a thorough text panel, and the illusive, weathered Safehouse Door (2008). The door carries with it the problematic history of the project’s initial site at KKProjects, an alternative art space active in the St. Roch neighborhood from 2007 until about 2011. After KKProjects’ director left town for extended periods beginning in 2010, the houses that comprised the project quickly degraded, sparking so much local controversy that Chin issued a response letter to an editorial in the local newspaper. KKProjects, and Chin’s Safehouse included, raised many questions about what is at stake in using a city as platform for engagement, artistic authorship, and adopting the community as a catalyst for change, particularly after instances of extreme devastation.

Both entering and exiting through the museum’s Grand Hall, visitors are overshadowed by a bamboo replica of the “Daisy Cutter” hanging overhead. Otherwise known as the BLU-82, this bomb has been deployed in both Vietnam and Afghanistan, and during the exhibition opening, small pieces of paper with a drawing of the bomb and a message to recipients flooded the large crowd from above. The succinct threat written in red ink and Arabic translates to “Flee and you will live | Stay and you will die.” The piece, Our Strange Flower of Democracy (2005), is a powerful reflection on our concepts of democracy and, as Chin states, a “reminder of what we must continue to critique,” be it our government, our society, or ourselves.

Exhibitions of conceptual and socially engaged or community-driven practices question how the display of artifacts and records alter the intentions and receptions of the original work. However, visitors of “Rematch” will not likely find themselves questioning these changes or the aesthetic values of the works presented, but rather considering the display of these works as sites of reflection on the “invisible things,” and a space for education and inspiration, echoing Chin’s remark that this exhibition is truly about the “constant battle within yourself.”

Download a Fundred Dollar Bill to color and contribute here.

Emily Wilkerson is a writer and curator based in New Orleans. She is a regular contributor to Pelican Bomb, and her ongoing research focuses on socially engaged art practices and the alternative educational strategies of international artist and curatorial residencies.