In the mid-20th century, central Kentucky experienced a renaissance when a prominent milieu of artists, writers, and thinkers contemplated philosophical, social, and political issues ranging from spirituality to the environment. The photographs in the exhibition “Ralph Eugene Meatyard: Photographing Thomas Merton,”on view through July 26 at Institute 193 in Lexington, were taken during this fervent period of Kentucky’s intellectual history.

The selection of images is a testament to the brief but poignant relationship between photographer Ralph Eugene Meatyard and Thomas Merton, the theologian, writer, and monk who served as his subject. Meatyard was an optician by trade and spent most of his life in Lexington. His interest in photography began as a hobby, and he soon developed a national reputation. He met Merton in 1967 at the Abbey of Gethsemani, where Merton was a monk, and they shared a productive friendship for two years before Merton met his untimely death while traveling abroad.

Because Meatyard is perhaps best known for his unsettling and haunting images of children and masked figures, the relative portraitlike quality of the Merton series initially seems like an anomaly. However, the photographs maintain some quintessential Meatyard elements. For instance, Meatyard has a penchant for costumed figures whose external appearances obscure interpretation and hide truth. Merton also appears in varied clothes, wearing either his habit, his pedestrian clothes, or, curiously, the attire of a farmer (a reference to Jonathan Williams). Because Merton, like many of Meatyard’s characters, is variously costumed, his true nature is simply unattainable or perhaps unfathomable.

Meatyard’s portfolio of Merton portraits numbers more than 100 images. The photographs in this exhibition have been culled from a larger 2013 exhibition of 29 photographs previously on view at Public, the Louisville Visual Art Association Gallery. While the Institute 193 iteration could benefit from readily accessible labeling and interpretation (though the previously published catalogue with insightful essays was available), the carefully edited selection of images and their thoughtful arrangement are both deftly succinct and touchingly trenchant.

Arranged in snug groupings, the relationships formed between photographs reveals the tendentious dialogue between Merton’s intense introspection and his public persona. The first grouping features Merton in the company of the writers that formed his social network. He wears his habit, but casually sips a beer with Meatyard’s wife and writer Guy Davenport. This curious juxtaposition reminds us of the tension between the monk’s meditative solitude and his desire to participate in a shared life experience.

The second grouping, perhaps the most enigmatic, is a series of five photographs that feature Merton dressed in habit, staticly posed in a variety of outdoor scenes. He appears mostly in solitude, befitting of his station, but each visage, posture, and setting changes how Merton is perceived. In one image, Merton looks upward and is drenched in sunlight like a modern-day Saint Francis awaiting his stigmata. In another, his back is turned to the camera, only his ominous habit forming the silhouette of his body. These photographs, hung closely in succession, imply the passage of time with changing light and tone, and perhaps foreshadow Merton’s imminent death. They are the most quiet but subtly moving images in the exhibition.

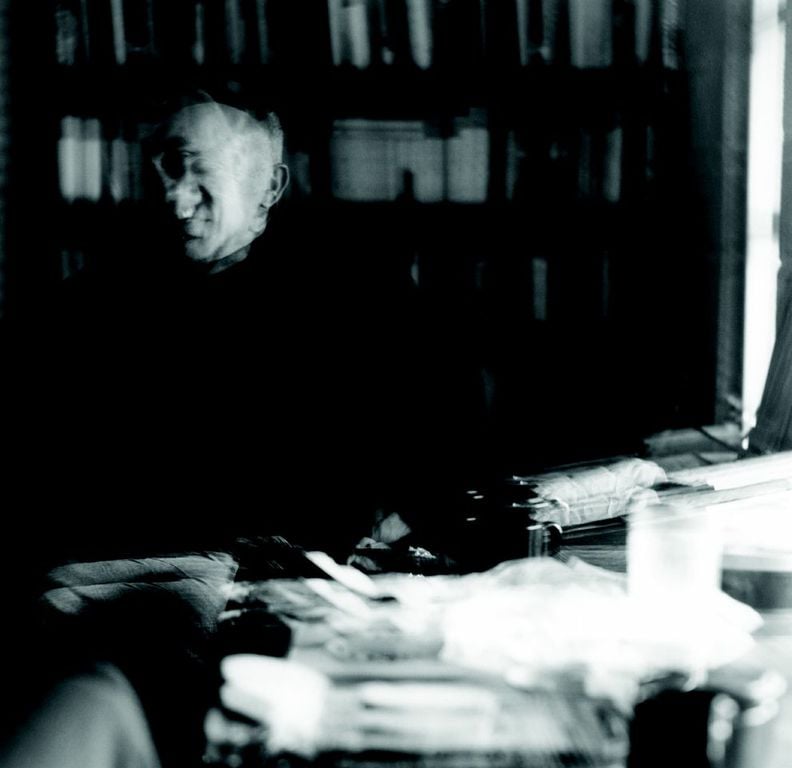

The serene narrative formed by that grouping is counterbalanced by another group of images that feature Merton in the company of his intellectual peers. Like many other Meatyard photographs, they are taken without clear focus and with long exposures that blur motion. So while Merton is the subject, he can never clearly be perceived. Perhaps that is the strength of the portraits as a collection. They reveal the complexities of the man behind the habit, the man behind the written words. There is exuberant joy and focused contemplation, there is friendship and utter solitude, and finally there is the spiritual and the earthly.

Eileen Yanoviak is the exhibitions and collections manager at the Kentucky Museum of Art and Craft. She is also a doctoral student in art history at the University of Louisville and adjunct faculty at the University of Arkansas at Little Rock.