You should know that Mary T. Smith displayed her art in her yard.

Her property in rural Copiah County, Mississippi, was filled with small huts and sculptures she constructed from the scraps of wood and tin from the junkyard next door. Her evocative, gestural paintings—made using house paint and the same junkyard metal sheets—were propped against these buildings and hung on fences. In the same Southern folk tradition exemplified by Lonnie Holley, Eddie Owens Martin (St. EOM), and Joe Minter, she used art as a means to create an oasis in an otherwise cruel world that ostracized her because of her gender, skin color, and severe hearing impairment, all of which lead her to end her schooling in the fifth grade. The sculptures, paintings, and buildings she constructed in her yard are a vast visual account of her life, hometown, and beliefs. Acknowledging that Smith’s work was both a fixture and a result of her local environment provides understanding of not only the art but the artist herself.

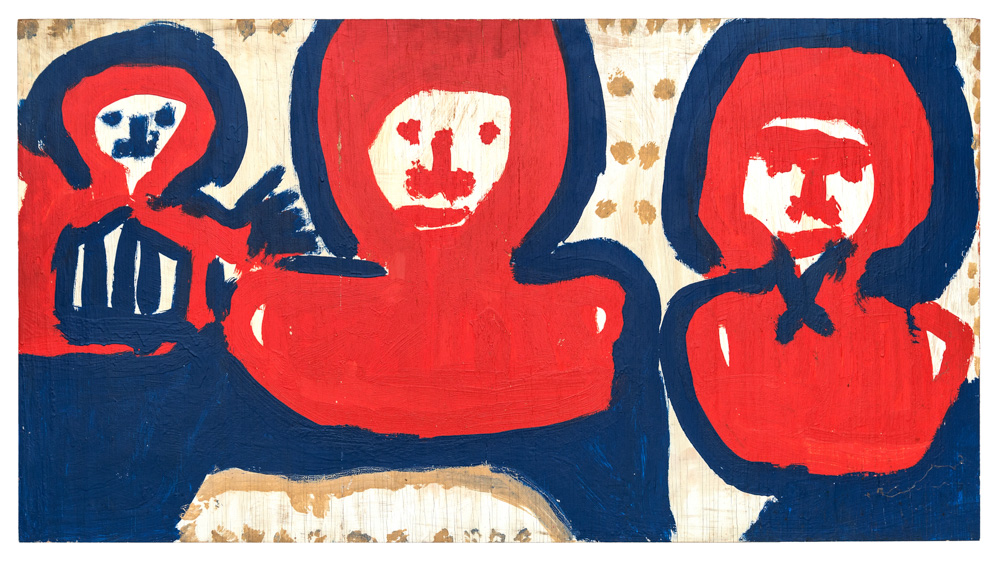

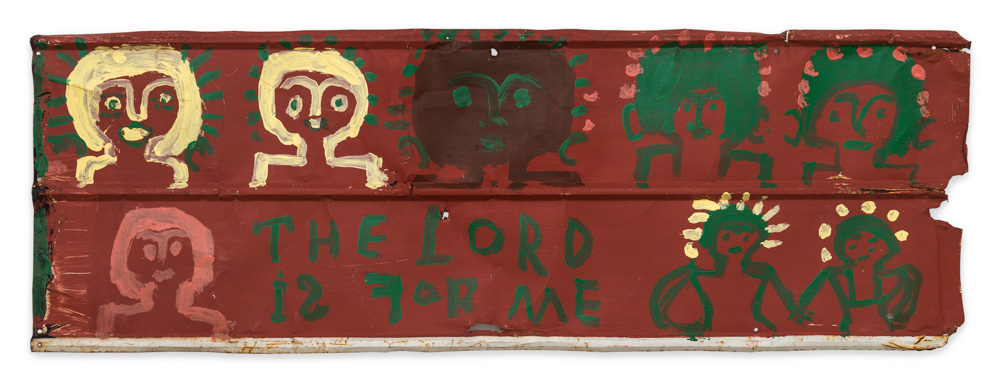

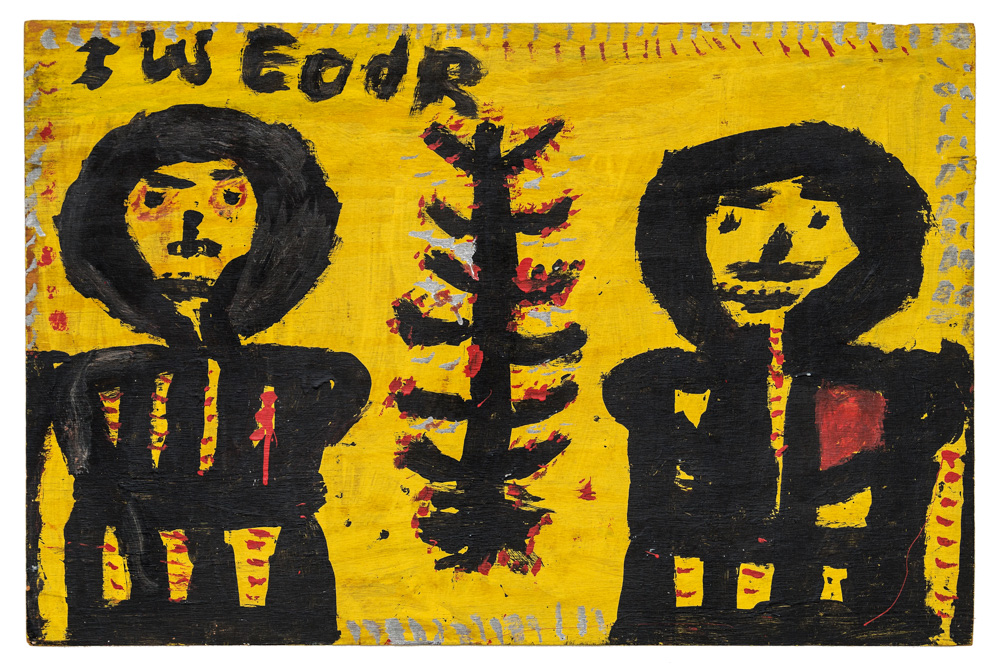

You should know that Mary T. Smith displayed her art in her yard, but there is no indication of this anywhere in Smith’s exhibition I WE OUR, which runs through July 28 at SHRINE, a lower Manhattan gallery specializing in showing the work of folk and self-taught artists. The show features a small collection of Smith’s sheet metal paintings from the 80s and 90s, displayed here on pristine, white gallery walls. The paintings feature human figures outlined in thick strokes of color, often surrounded by short sayings that are misspelled. The overall visual content of these paintings is up for interpretation, but her thematic preoccupation with spirituality and her neighbors is clear. In The Lord Is For Me, there are multiple small portraits, all painted in different colors with markings that suggest halos. It is a hopeful view of a community united by belief and, considering that Smith lived in still-highly-segregated Mississippi, a bittersweet portrayal of a utopia that Smith may not have ever experienced but still had the grace to imagine. The namesake painting of the exhibition, I WE OUR, features two simple figures outlined in black—one detailed with unnerving red marks—and a tree on a yellow background, with the painting’s title scrawled in the upper-left corner. Another standout painting is AMA, which is unframed and grouped with other smaller paintings. AMA shares a similar composition with I WE OUR, but the smaller scale of the sheet metal pushes the figures and text together, adding an underlying sense of urgency and discomfort that is not present in Smith’s other paintings.

A sense of life—a hectic, troubled, and joyful one—is nearly palpable in these paintings. Despite this obvious presence in the paintings’ content and expressive strokes, there are no wall texts, labels, nor any biographical information displayed alongside the paintings. While this is typical of a commercial gallery, the absence of information here feels jarring since Smith’s work is enriched when her life story is considered. In SHRINE’s press release, they state that “while it is common to focus on the biographies of self-taught artists, the most striking aspects of Mary T. Smith’s paintings are their effortless confidence, originality and competence, which make them strong examples of American contemporary art. Her images are bold, vibrant, and relate much more to those of better-known artists such as Jean-Michel Basquiat or Georg Baselitz than they do to anything in the traditional folk art category, to which her work has typically been relegated until recently.” Placing the work of a long-neglected folk artist in conversation with more established artists is a fine and admirable goal in a world where all things are equal, but all things are not equal.

Elements in Smith’s paintings, such as the misspelled words and her use of sheet metal as canvas, that are directly linked to the inequality she faced on a daily basis and her precarious economic situation. Although Smith did sell many of her paintings in the height of her career, she had next to no income at the time of her passing in 1995 and faced varying levels of poverty in her lifetime. Both her father and second husband were sharecroppers, and Smith worked as a maid before she devoted herself to her art in her mid 60s. When she died, distant friends and admirers volunteered to pay for her funeral costs when her family couldn’t afford a proper burial. [1] Decades after her death, self-taught art has become more popular with institutions and collectors, making Smith’s work much more commercially viable now than it was when she was alive. Her art is included in the permanent collections of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Smithsonian American Art Museum, and the High Museum of Art, largely due to donations on behalf of William Arnett and the Souls Grown Deep Foundation. Most of Smith’s work has been privately sold at auction, but many of these sales come from the estates of collectors such as the late Tuscaloosa collector Robert Cargo, not from an estate set up on her behalf. Despite her growing popularity, Smith’s family or any other beneficiaries likely receive very little of any financial security she could have provided from the grave.

Smith’s powerful work deserves careful attention and critique on its own formal merits, but this must be accomplished without anonymizing the unique context of an artist who is still an unknown to most even within the art world. Aesthetically, her work is in conversation with not only other prolific folk artists but other luminaries of late twentieth-century contemporary art. Other writers such as Edward M. Gómez of Hyperallergic have correctly compared Smith’s vibrant use of color to that of the aforementioned Basquiat and American painter Al Held. [2] And while there are merits to presenting Smith’s work without it being solely defined by personal narrative, the artist’s own story needs to be shared, especially while museums, galleries, and academia tend to neglect artists of color and artists from the Global South. Smith is an important artist in both the folk movement and the entire ecosystem of twentieth-century Southern art, and it is important to reckon with the systematic racism, ableism, and misogyny that influenced not only her artistic output but the way it is received now. One of the best ways that institutions can do this is by amplifying the stories of artists like Smith so that they are not further anonymized by the very places that have the ability to preserve their lifework. Therein lies the issue with I WE OUR and other exhibitions like it that neglect the personal struggles and social factors that lead to an artist being considered a “folk” or “outsider,” thus allowing for misrepresentation and fetishization of the artist and their work. Seeing representation of Southern folk artists—especially such artists who were Black women from the South—in gallery spaces like SHRINE is a sign of growing equity in the arts, but ethical representation is just as important. We need to create context that explains the motivations and struggles behind artworks while also acknowledging why art like Smith’s has been kept in the margins for so long. Smith cannot literally speak for herself in the way that contemporary artists now can, but her art still sings loud and clear. Unfortunately, SHRINE’s presentation of I WE OUR failed to showcase Smith’s voice by not representing who she was outside of her now commodified artistic output.

Today, you can walk into SHRINE, see fantastic paintings by an

artist who may as well have been anonymous, and purchase one of these paintings

for more money than this artist ever saw in her lifetime. But you should know

that this artist is Mary T. Smith, a disabled Black woman who lived and died in

rural Mississippi with a fierce love of Jesus and without a penny to her name.

Her art was her life, her diary, her primary coping method. She displayed her

art in her yard.

I WE OUR is on view at SHRINE in New York through July 28.

[1] William Arnett, “Her Name is Someone.” Souls Grown Deep Foundation.

[2] Edward M. Gómez, “The Bold, Blessed Paintings of a Sharecropper’s Daughter,” Hyperallergic. June 8, 2019.