When the Contemporary Arts Center (CAC) announced its exhibition “Mark of the Feminine,” a colleague asked what I thought of the show’s concept. His tone was somewhat sly, as if he was predicting—as it turned out, correctly—how I would respond. My immediate reaction was, “oh, that’s horrible.” Part of my gut reaction was to the word “mark.” To be marked by something connotes something negative. Like branding. A scarlet letter. Shame.

Then there was the question of the selection criteria. Was it enough to be a woman to be accepted to such a show? My colleague pointed out that the criteria were even broader, including those who identify as female (even if not born into the gender). He concluded that it was just another NOLA: NOW group show, an annual series of exhibitions featuring local artists that started under that name in 2011. When staff curator Amy Mackie left the CAC, the program ended. Independent curator Regine Basha was invited to New Orleans to resurrect the series, and she chose 54 works from 30 artists out of a pool of 343 applicants. The politics of NOLA: NOW raises a question: Is it a group show of local female artists, or is it a show about gender? To answer the first question in the affirmative runs the risk of perpetuating essentialist notions of female identity that can be damaging, so I was hoping for a show that interrogated the concept of the feminine.

The curatorial statements seem somewhat apologetic for the title, as if the curator needed to back up and explain that the concept of the feminine is not being claimed here but is up for debate. I can imagine her saying, “don’t get too upset,” in other words, “I’m not trying to say that there is a feminine essence, and I know that postmodern feminist art already deconstructed essentialism.” In fact, the text at the entry to the gallery argues that the “feminine,” placed in scare quotes, “speaks to a timeless yet ever-evolving set of greater shared human concerns affecting our society at large.” This did not make me feel better, as it simply avoided the question of what marks the feminine by claiming that female concerns are universal. So, instead of making a show of “woman artists” (a phrase that I have always hated, since we don’t use the phrase “man artists”), the language was updated to recognize that it is now common to speak of gender as something that people choose, by identifying with the “feminine” or the “masculine,” as if those terms are stable referents. I know that, as a female viewer, I am supposed to identify with the show, with its concerns. But the problem is that I did not choose to identify with the feminine; society chose that for me. As soon as I was born, that checked box on the birth certificate defined me as female. Even if I did not like playing with dolls, did not like the color pink, I was still female. It was precisely NOT a choice. In that sense, it is definitely a “mark.”

Identification is a tricky business, as I learned from reading Lacan, that never actually works. I am tempted to generalize, to say that the problem for women is that we never fully fit the feminine, and the places where we don’t fit always feel like failures. For me, that failure is a lack of interest in and knowledge about makeup. All of my riot-grrrl, post-feminist leanings cannot void the sense that something is wrong with me because I do not enjoy Sephora. It is disappointing that all of the good, hard work to complicate gender has actually been simplified in our new rhetoric of gender identification. The ambiguity that Judith Butler wanted to see is gone. We are not moving past gender; we are stuck with the poles of feminine and masculine and now told to choose one or the other. We have completely lost Lacan’s insistence on the misidentification of identification.

Some of the artists in the show recognize this lack of fit. What is feminine strength? Natalie McLaurin appropriates signs of male power to comic effect in her photograph Beard Measuring Contest. Monica Zeringue adapts mythological sources in her works based on the Roman she-wolf and Narcissus. Contrast this to Vanessa Centeno’s Keep it Up, a huge pile of phallic forms that she calls “ding-a-lings.” The sculpture came out of earlier work with strap-on dildos, dipped in glitter for that feminine effect. Here, their state of erection is in doubt, as the title plays with the associations of the word “up” and the reminder to just keep working at it, whatever it might be. The phrase also refers to the frustrating search for artistic expression and authority in a world where those qualities are associated with the masculine.

Some of the works explore or refer to traditional female roles, such as Kathleen Loe’s monumental ball gown in a black and white wash, the white gloves of a debutante present, but her body is missing. Titled The Life You Save May Be Your Own, the painting clearly does not illustrate those words. For me, the title conjured up thoughts of domestic violence and assault but also the poetry of saving one’s own life by refusing the trappings of a stereotypical femininity.

36 by 36 inches.

In The Banquet Table, a video documenting a performance, Amanda Cassingham-Bardwell’s hostess, wearing an old-fashioned white apron tied around her waist, seems out of place, as if she is playing the straight man in a comic skit. The presentation and the food recall a dinner party that Betty throws for Don’s clients on Mad Men, but Cassingham-Bardwell’s hostess serves wacky foods such as coffee aspic, pink pickled eggs, caramel-covered Cheetos, and chocolate-mayonnaise petit fours. Also counting on comic effect is Sarah Sole’s Passionate Something, a painting of Hilary Clinton in a ruffled white apron, because we know she’s not the type who stays home with the kids and bakes cookies. Perhaps her lack of maternal qualities explains why the majority of the American voting public did not support her political bid in 2008 for the ultimate male sign of power, the presidency.

Other works on view relate to the masculine, or layer the masculine over the feminine. For Maxx Sizeler, his work reflects on his choice to reject female identity in favor of the masculine. The paintings of dreamlike model cars in pastel colors riff on the toys that children are expected to play with: cars for boys and dolls for girls. To be a girl and play with cars is one of those examples of misidentification: the girl fails to play with dolls, and thus fails to identify with the feminine. But these cars have great names like Crewzing Shark and Pickle Power, and they look fun to play with.

20 by 24 inches.

In other examples, women take on roles associated with men. Edna Lanieri’s photograph First Round Knockout is particularly striking. It focuses on the face of a female boxer, her arms held up and her eyes suspended in shock after receiving the punch. The ironically named artist Boyfriend adopts the tropes of rap videos in Like My Hand Did, the title of which refers to the song’s chorus “all because you didn’t make me come like my hand did.” Wearing big glasses with bright red frames, our heroine is definitely not the glamorous sex object found in rap videos. She mocks the bravado of rap songs, at times acting as if she is a male rapper bragging about his conquests. But then she slips back into a female character and uses that male bravado to taunt her boyfriend about his lack of sexual prowess. The tone is blasé, as if all of this has happened a thousand times before and is actually quite boring. But the music is an earworm.

“Mark of the Feminine” is completely uncompelling as an exploration of the feminine, despite its inclusion of some very strong work. Themes arise in the imagery but are not defined in any of the wall text. Hair turns out to be one of the primary themes of the show, established by Natalie McLaurin’s beard photograph at the beginning of the exhibition. Alisha Feldman’s comic panel diagrams the history of her hero’s body hair, mixing references to both the feminine and masculine. Ariya Martin’s video presents the artist’s hand cutting the ear hair of a male companion. The sound of wind chimes and traffic fills the background as her scissors slowly zero in on each hair. The remnants of red nail polish on her fingers at first look like blood, and the potential for blood streaming down the ear from a misplaced cut makes the video hypnotic.

Other themes include family, relationships (especially romantic ones), racial identity, and sexual identity. Carla Williams’s All the Women In My Family is a collection of reproduced snapshots, presumably documenting all the women in her family. Such images could be used to ask whether the African American experience of femininity differs from the white experience, but there is little here to draw out the question.

I was particularly drawn to Jennifer Shaw’s photograph Belly, in which a child’s hand is pressed wide against a mother’s belly, exposed by her bikini. It recalls the physical intimacy of a mother and child, a lost intimacy that seems so strange in retrospect and yet so natural in its experience. Then there is the irony of the title Marital Bliss for Ronna Harris’s painting of a married couple seated on a bed—they definitely do not look happy. Or there is Meg Turner’s A Decade of Loves, a collection of 8-by-10 photo booth images showing the artist with both male and female “loves.” The images are sometimes romantic, the couple caught by the camera mid-kiss, and at other times quite goofy.

Where the strategy was to let the work speak for itself, questions may arise about inclusion. Is Valerie Corradetti’s photo If I Lie, I Lie Because I Love You here because it uses the color pink? Does that constitute an exploration of the feminine? Or is it here because Corradetti is a woman? The work, an abstract landscape constructed from torn photos and sugar crystals, certainly meditates on time, ephemerality and landscape in a powerful way, but it does not pursue what I understand as the mark of the feminine.

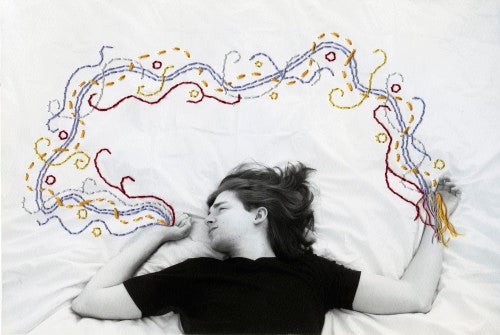

Other choices seem more strategically planned. There are nods to ’70s-era feminist art, when artists used craft techniques associated with the feminine. This would explain the significance of embroidery in Hannah Joyce’s photographs, or the inclusion of Connie Shea’s woven wool yarn abstractions. Shea’s works remind the viewer that not all women have to make art about identity; they can make abstract art too. We could even make an art history quiz out of the potential links between the works in the show and feminist art history: match Vanessa Centeno with Lynda Benglis, especially her infamous dildo ad, and Cassingham-Bardwell’s banquet to Judy Chicago’s Dinner Party, and Zeringue’s Odalisque to Sylvia Sleigh’s perversions of Ingres.

Then there are nods to ’80s era feminist art, post-essentialism. References to gender as performance, à la Judith Butler, are expected, so we have Edna Lanieri’s photographs of drag queens at home, their faces revealing the makeup that transforms them from male to female. Cathy, for instance, is seated in front of the camera, wearing a dark silk robe that reveals his chest hair. His lips are outlined in a feminine shape, the brows painted on, and fake eyelashes applied: a demonstration of the artificiality of signifiers that the rest of the world reads as female.

Nina Schwanse and Sophie Lvoff’s take on Martha Rosler’s Semiotics of the Kitchen might well sum up the problem with such references to the history of feminist art. In Semiotics of the Taco (after Martha), Lvoff is standing behind a table, dressed in a ’70s-style blouse with a floppy bow. Mimicking Rosler’s demonstration of kitchen implements, she shows how to make a taco dinner. Since she is making tacos from an Old El Paso kit, you might expect that Rosler’s deconstruction has simply been moved from gender identity to the realm of cultural identity. But that point is never quite made; we don’t learn the lesson that Old El Paso might not be authentic. It almost seems as if the artists have failed to understand the point of Rosler’s critique, which was to misuse the signs as a way of showing us how those signs actually operate.

Here, things don’t make sense, like the way she is chopping the lettuce more ferociously than is necessary. Why is there Fantastic cleaning spray? Why aren’t all of the letters of the alphabet included? Car wax? What does that have to do with tacos? Why didn’t they cover up or edit out the mistakes—like when things start falling off the table? It is definitely endearing to see Lvoff laugh in those moments, as if she senses that the whole production could fall apart at any moment. Or as if they are just playing dress-up, two little girls raiding mommy Rosler’s closet. At the end of the video, Lvoff imitates Rosler’s slash of a Z, the knife moving through the air, but without any of Rosler’s emotion or intent. Perhaps they cannot identify with Rosler, with her generation, with what feminism was before them.

And that is a huge part of the problem that this show reveals: lack of knowledge of the history of feminism, lack of access to that history, lack of understanding of what feminism is now, why it is needed. We live, or so we’re told, in a postfeminist world. For some, that means that we no longer need feminism—the advances have been made, everything’s okay, no one looks down on women anymore. I am not in that camp, as I see how sexism continues to put up ever more subtle stumbling blocks. The recent Emmys provided even more obvious signs—like putting Sofía Vergara on a rotating pedestal as an example of how television’s “success is based on always giving the viewer something compelling to watch.” Ouch. A quick Internet search reveals that I wasn’t the only one troubled by that moment, but the rhetoric around it is telling. It seems as if everyone thought, “did that just happen?” In other words, shouldn’t we be well beyond that by now? Or, are we still marked as targets?

“Mark of the Feminine” is at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans through October 4.

Rebecca Lee Reynolds is an assistant professor of art history at the University of New Orleans.