I grew up riding in school buses and the backseats of my parents’ cars, being dropped off in museum parking lots across the Greater New York City area; later, I went to college at an art school in Chicago that was physically attached to one of the largest encyclopedic museums in the country. If there were stories about how the art arrived at any of these places—unless they explicitly involved murder, adultery, or crimes committed by really attractive or homely people (or ideally, a couple involving one of each)—I was not interested in reading them. Besides clicking on the occasional headline, I gave the idea of how museums went about putting their collections together very little thought or energy, until I had some time to kill before my niece’s college graduation this summer and wandered into Making Connections at the Weatherspoon Art Museum in Greensboro, North Carolina.

There’s an anecdote I’ve edited out about something that happened to me at a bar after visiting the museum, but suffice it to say: stories are often the best part. They’re how we make meaning out of life’s events, and they offer us a framework to ascribe emotional significance and priority to objects and experiences that might’ve otherwise passed us by. Stories, tales, and recollections are incredibly important, and Making Connections, an exhibition showcasing the Weatherspoon’s permanent collection, is literally full of them. Although most of the work on view is great, the real stars of the show are the wall texts, which take great pains to describe how the works arrived in Greensboro and also the many roles the members of the Greensboro community have taken in making the museum what it is today.

Exhibition standout The Song of the Ravens (2014) by Julie Buffalohead is a massive work on Lokta paper, showing a man seated on a brown sectional couch, pointing a gun in the direction of a coyote standing on two legs, wearing a pink, 1950s-era house dress. Above this possible couple is a herd of flying ravens (technically known as an unkindness) surrounding or escaping them. Lower in the picture are an array of woodland creatures near the gunman, possibly shot dead. The mythical piece is further animated by a wall text contributed by Molly Stouten, a retired art teacher and Greensboro Community Member, who writes, “Click-Crack! Aaaak! Each time I return to The Song of the Ravens, I feel like I hear it before I see it.”

Stories are tendons: tools to link experience with information in the hopes of garnering some sort of emotional and relational appeal. Encapsulating the thesis of Making Connections is Elsa Dorfman’s Before, During and After March 2, 2013 (2013), a giant triptych of 20 x 24-inch Polaroid photographs featuring former Weatherspoon docent and current Greensboro resident Caroline Panzer, along with her three adult daughters, one of their partners, and, in the final image, the Massachusetts-based artist herself. In this, we have an example of art and artist being shaped by and encouraged to be interpreted by their relationships.

In terms of relationships, institutions mean different things in different places, and as a North Carolina virgin, it was interesting to try to imagine what this exhibition might be able to say about the state, the city, and/or the values, dreams, and ambitions of its inhabitants. I think I get the gist of what an Alexander Calder sculpture means in most places, but what could it mean here right now, in an exhibition centered around ideas of the museum and its relationship to its community? Which begs a larger question about art history as a whole. With several art history titans, such as de Kooning and Matisse, sharing space with lesser-known artists, it was refreshing to see an exhibition with no qualms about seeming lopsided.

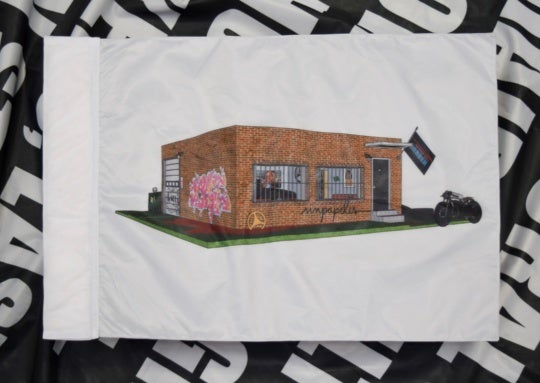

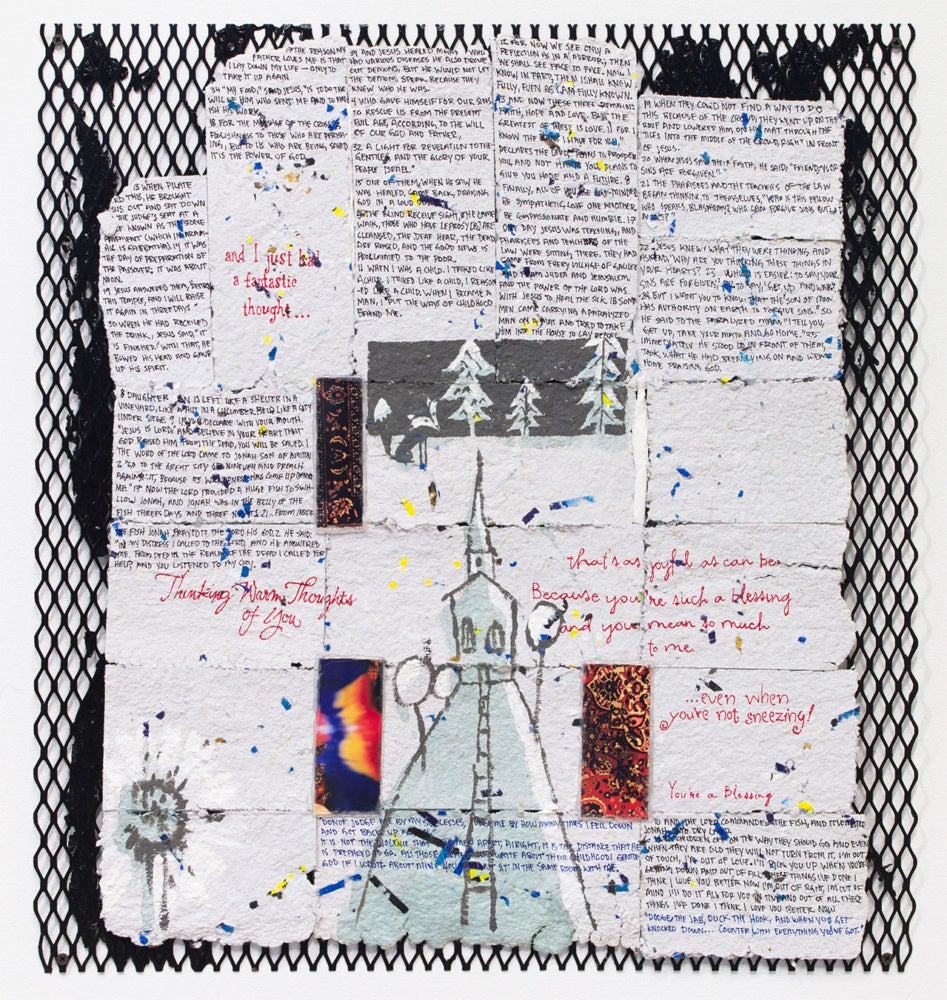

Among the heavy hitters: the sexy aforementioned Calder mobile the museum made a point of mentioning it purchased one year after it was made; a mustard Frankenthaler that won’t quit; a Rauschenberg I didn’t mind, one that the wall label admits was hated at the time of its purchase; a mostly black flirty painting by Al Held; as well as a painting by Bauhaus legend Josef Albers along with a really helpful reminder of North Carolina’s Black Mountain College, which he directed at one point before going on to change the history of color theory at Yale. There is also work by artists from or based in North Carolina, like an interesting and unexpected collage by Sherrill Roland and a bizarre portrait of a Black woman in blackface titled even more curiously, Remembering Mom (2003-2004) by Greensboro native Beverly McIver, which does make the viewer question what the story is there.

Which brings me to my other point: despite the nearly ubiquitous, nefarious, and exploitative means that most museum collections and acquisitions have been funded by, these kinds of stories are largely absent from the show. To that point, the museum also doesn’t really discuss or dwell on the darker subjects of some of the artworks or in the artists’ biographies. When it comes down to it, I honestly couldn’t have felt more relieved. The objective and best part of Making Connections is its animated, Disney-like dream of optimism. There’s a suggestion and assertion that things like being human matter, and that with each exchange and transaction, the lifespan of an object can grow almost exponentially. Memories, reflections, and interpretations can be a worthwhile and positive provenance of their own, and, no matter a person’s roles or positions, everyone who experiences a work of art can contribute and have a say. It’s most likely a fantasy, but Making Connections says that community can be worldbuilding, even if that world only seems to take up just three small galleries. I left the museum feeling hopeful, wanting mostly to believe them.