During my visit to In Translation: Jonathan Bouknight, Ben Schonberger, and Nathan Sharatt exhibition at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center, I found myself asking a number of times: “How do the works in this show fit together?” The conclusion is murky, at best. Curated by ACAC artistic director Stuart Horodner, the concept behind the show is almost impossible to grasp by mere viewing. The idea that is supposedly being explored is an interesting one, but it seems an after-thought used to package these particular artists together. What the viewer is intended to investigate is the outcome of each artist’s transformation of a “provocative original.” This thought has strength, and it would have been interesting to see it played out in a more cohesive manner.

Schonberger’s project Beautiful Pig consists of snapshots taken by Marty Gaynor, a retired police officer from Detroit, of “criminals” before their arrest. Many questions came up that left me feeling uneasy. Whatever happened to “innocent until proven guilty?” Did Gaynor ask the “potential criminals” for permission to take their photographs? I know I wouldn’t want a candid taken of me if I were ever under arrest. Issues of basic human rights like privacy arise. Was this his version of “trophies” from his days on the force?

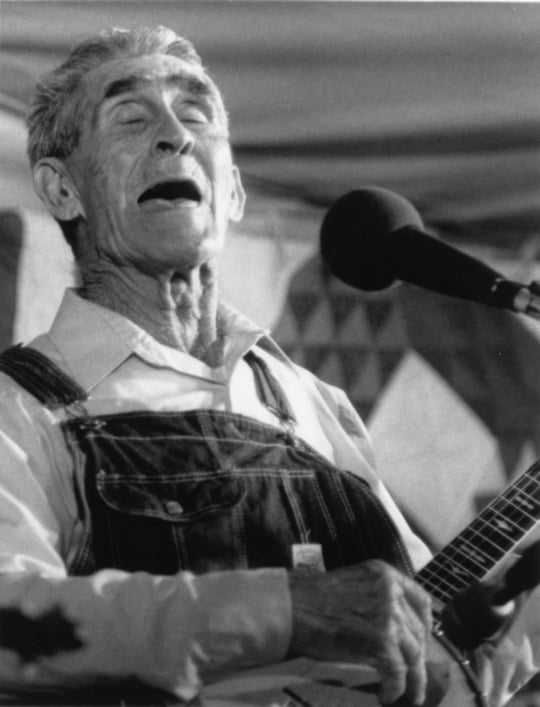

Schonberger pushes for clarity by having Gaynor to “annotate” the images. The cop gets his own moment in the spotlight in the large portrait, Sergeant Marty Gaynor: Systems of Identification, Occupation and Faith. It would have been interesting to see Gaynor in a similarly unguarded predicament, but instead we find him in the comfort of the Jewish synagogue he grew up attending, along with his badges of victory and self-affirmation. His police uniform and on the job accessories like handcuffs collide with his prayer shawl and yarmulke, implying a possible religious justification of his acts. There are definite points of engagement and interesting questions raised here, but the significane of the arrested citizens’ photographs is lost in Schonberger’s translation.

There is an effective translation between Bouknight’s video and 2-D work. The artist has been filming couples in motion over the past year,, and the particular video on view shows the entangled forms of a man and woman shifting languidly through an interior. While watching the footage, Bouknight then made blind contour drawings of the couples’ movements with acrylic black paint on Mylar and butcher’s paper—simple yet potent. The effect is mesmerizing . Life’s qualities of flux and impermanence are reflected in the feeling that these drawings might morph entirely into some other configuration as you stand there.

The drawings seem to be a more personal body of work for Bouknight than his video pieces because they flowed freely from his mind while he was concentrating on something else. A sort of puzzle is created in trying to figure out what frame he pulled “that eye” or “that nose” from. I would be interested to see a show of all of his video work paired with natural reactions like these in even more varied forms of media.

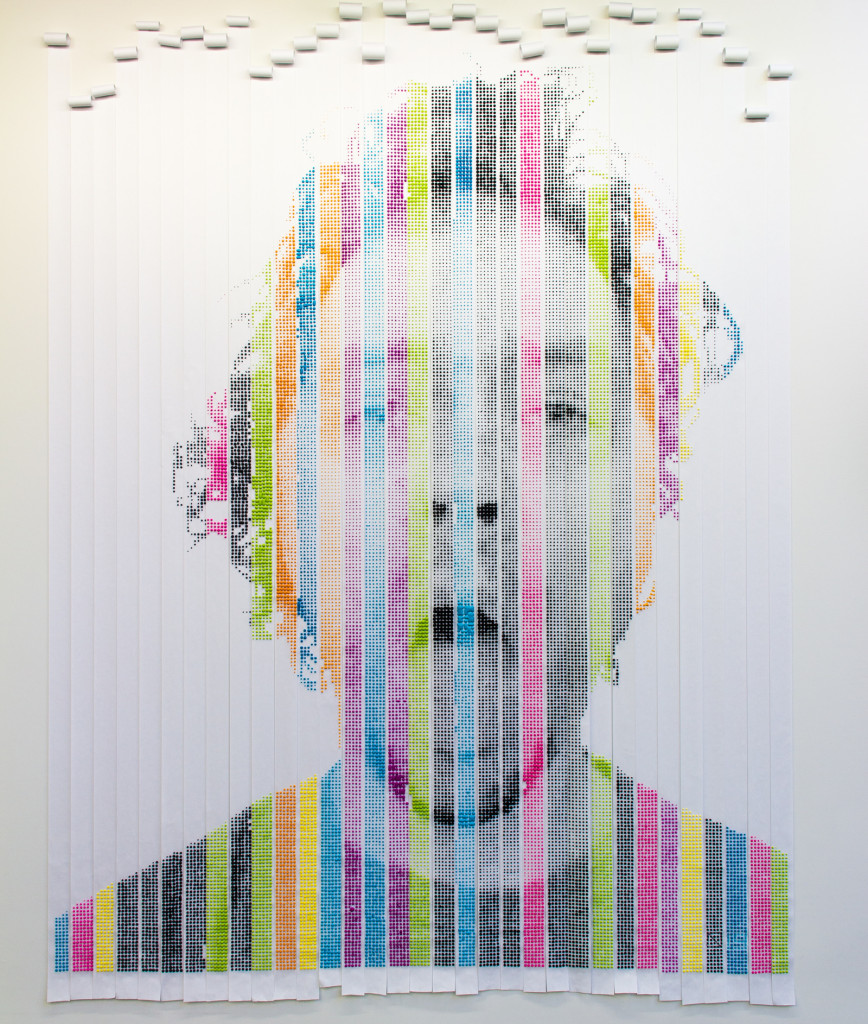

After reading Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Sharratt was inspired to view his studio as a laboratory of sorts, to try to create “new information systems” using 3-D modeling software and inkjet plotters. What’s presented, however, is a huge selfie of the artist, Bathroom Selfie In Sugar and Spice and Also Ants, a composition of paper strips and pixel-like candy dots that could possibly be the next design for an Urban Outfitters T-shirt. My interest was not piqued by any technological savvy, such as a 3D print of a hand on the floor, or by the inclusion of text from Shelley’s book, which was applied to the wall but then obscured by unintelligible vinyl lettering and Sharratt’s own scrawl. I was told that this installation would be ever-changing, with the artist adding and taking away pieces throughout the show’s run.

The entire show would benefit from a more defined curatorial vision and a better dialogue among the artists’ works, which might at least remedy its thrown-together quality. This is not to say that there is no good or interesting art on view here. If you don’t rely on the theme for explication, you will find artists who warrant further investigation and works worth your time.

Sherri Caudell is a poet and freelance writer from Atlanta.