Artist and musician Lonnie Holley (b. 1950, Birmingham, Alabama) said that people like him offer alternative ways of “making, thinking, living, and being.” He then asks himself has he done enough? If the works on view in his impressive and challenging solo at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art are any indication, he has done quite a lot. And it’s only a fraction of his prodigious output since the early 1990s, when he first became seriously engaged in art, after carving headstones for two of his sisters after their untimely death (he comes from an improbable family of 27 siblings and has 16 children of his own). If it is not enough, it is only in the sense that he’s not done; objects continue to pour from his miraculous, be-ringed hands as if from a spigot on full blast.

Evocatively titled “Something to Take My Place” and cannily curated by Halsey director Mark Sloan, it was selected from Holley’s personal collection, William S. Arnett’s collection and the Souls Grown Deep Foundation (which recently donated a significant gift of artworks to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York). The roughly 40 works span his career, but the emphasis in this exhibition falls on the last decade and on single objects, not his spectacular environments. Each work is spotlighted, so that their complexity as art could be appraised, appreciated, not seen as merely as part of an installation. Holley’s work, as well as Thornton Dial’s and others, are too often filtered through the label of vernacular, self-taught and folk art with its categorical bias, its codified hint of condescension toward work deemed naïf, however visually astonishing. Holley’s power, however, lies in his particular vision, in his imaginative mix of form, autobiography, politics and morality.

Holley is a natural assembler, a homespun Picasso in terms of his affinity for unlikely materials to make sculptures, deftly, elegantly melding narrative with formal solutions. He went dumpster diving long before it had eco-cachet, out of need, where he salvaged discards such as bottles, barbed wire, rocks, shoes, clothing, anything that had found its way there, first to sell, then for artmaking. Grandmama’s Bottomless Bucket (1999), a long stick of wood hung on a wall pushed through a tin bucket with no bottom, is a memory of those visits, where he first learned the value of recycling, repurposing and preservation.

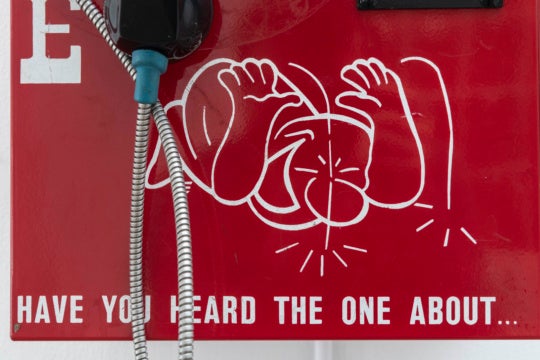

His work is tough but also unexpectedly fragile in places. He piles on barbed wire as if it were lace in elaborate works such as Table of Discussion (2005) and Like a Slave Ship (2008). Holley’s works are characterized by his eye for contrasting textures, the intricate balance of solid and void, the relationship of part to part to whole, acrobatic spinning of material, and a syncopated, sometimes snagged flow of movement throughout. The color is muted, faded: rust, silver, white, black, pale blue, the colors of different woods, cut through by bright red paint at times, symbolizing blood, as in Three Shovels to Bury You (1998) and Blood on a Rock Pile (2003), referring to a beating when he was a boy that nearly killed him. Changing Power (2014) is an upright lamp minus a light bulb embellished by a coil of electric wiring he salvaged from the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston during its renovation in 2014. An emblem of ruptured connection that was made before the killing of nine of its members this past June, it is all the more poignant after it.

Some seem purely formal until you read the titles, such as Will the Circle be Unbroken (2011), which appears to be a series of intersecting metal rings and the lovely, pale blue Bow Water (2002), which suggests a monochrome abstraction. Some are humorous, but double-edged, such as You Put the Clown Suit On (1993), a cross between a scarecrow and a crucifix, its gingham dress turning tragedy into irony.

Holley’s life has been one of exceptional hardship. However, it is not his life that this show celebrates but the art. It is not the hardships that made him an artist although it provided and shaped his subjects. It is his particular vision, no more circumstantial than any artist’s, and no less, a testament to his will, his endurance, and fortuity’s grace.

“Something to Take My Place” is on view at the Halsey Institute of Contemporary Art in Charleston, South Carolina, through October 10.

Lilly Wei is a New York-based critic and curator whose writing has appeared in such publications as Art in America, Art & Auction, and Artnews.