Because of its proximity to New Orleans, historically a much more visible port of entry, the city of Baton Rouge has often been overlooked in terms of the role it played in bringing enslaved people to the American South and the northern Caribbean. In her current show at the LSU Museum of Art, The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came, New Orleans-based artist Katrina Andry has given Baton Rouge the chance to engage in a particularly difficult but necessary confrontation with that painful history. As a native of Louisiana’s capital, I felt an acute implication of historical complicity suggested by an untitled installation of small silhouettes in freefall, the image of their collective peril forming a metallic hive off to the corner. Each reflective contour encourages museum-goers to consider the place of Baton Rouge within the history of slavery. This installation is presented alongside a series of eight prints aligning the walls of the museum’s C gallery.

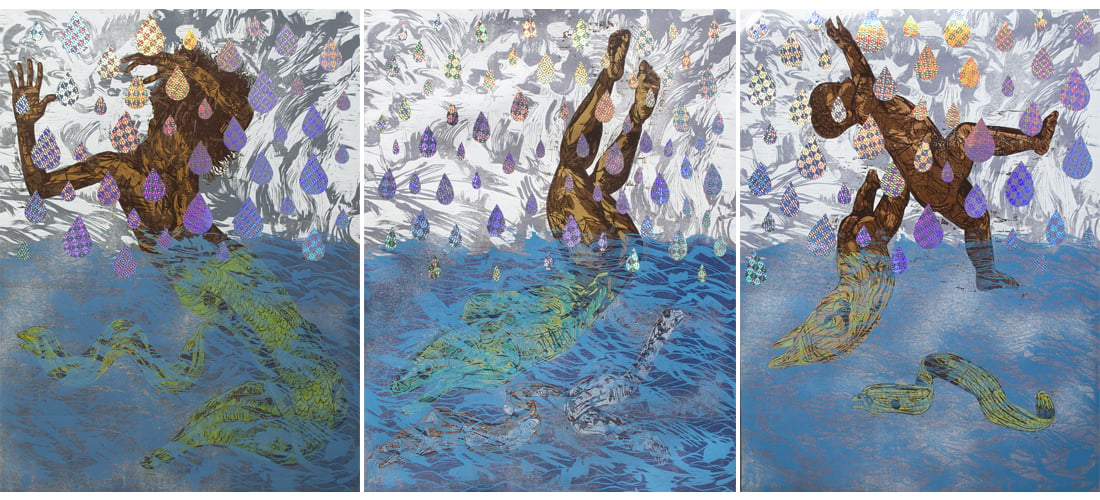

Like Andry’s works currently on view in the concurrent exhibition Katrina Andry: Depose and Dispose (of) at the Pensacola Museum of Art, the prints comprising Promise of the Rainbow offer us images of Black bodies in distress. Viewers see these figures mid-plummet, just as they’ve crossed through the waterline that bisects each print, nearly cutting each image in half. Above this line, a human figure appears. Below, a freshly polymorphed eel is shown instead, sometimes accompanied by other unfortunate souls. The skies are positively turbulent, variously depicted as either churning gray patterns or grayscale photographs of storm clouds within which large iridescent raindrops fall. The falling figures are rendered in overlapping panes of dulled blue, softened green, and umber.

Andry’s choice of mylar film as a base for the prints serves her very well. Each layer of ink sits unabsorbed and vulnerable to eyes probing for procedural imperfections, of which there are close to none. Through her exquisite and agitated application of linework, the overladen designs work to manifest a tangible surface but never quite merge into a cohesive whole. This fantastical quality, like the prints’ painful subject matter, incites a form of magical thinking that may cause the viewer to wonder, “What if those first captives thrown overboard along the treacherous middle passage didn’t drown? What if their suffering was muted by some gracious higher power? What if they simply joined the sea?” Along with the biblical reference in the exhibition’s title, speculations such as these position viewers in the first-person perspective of both the Old Testament Noah on his ark and the historical European slavers aboard the decks of their horrific vessels—as though, in a state of half-trauma and half-nonchalance, each looked upon drowning strangers and knew their actions would become infamous.

The history of artists addressing the Middle Passage—Black and white, contemporarily and historically, American and otherwise—provides essential context for Andry’s prints in The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came. Debuting at the Serpentine Galleries in London last year, Sondra Perry’s exhibition Typhoon Coming On directly invokes J.M.W. Turner’s 1840 painting Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhoon Coming On. Turner’s treatment of the African figures in his painting is essentially romantically callous: the water appears littered by suggestions of corpses, most notably a feminine leg surrounded by hungry sea life toward the bottom-right of the canvas. Pursuing radically different ends, Perry’s large format soundscape and video installation is figureless in each of its renditions as a kind of somber homage to the uncounted victims. Even Turner’s imagery of water glitches into a digitized violet corruption as if rejecting the lax treatment of such catastrophes by art of the past.

In her prints, Andry substitutes the historical realities of death and disappearance with sublimation and transmutation. Her images re-fashion the conventional imagery of Black trauma, rendering it strange and unfamiliar. At a time when images of Black trauma are circulated casually by news media and individuals alike, Andry’s prints remind us of the unplumbed—and perhaps indecipherable—depths of lost history.

Katrina Andry’s solo exhibition The Promise of the Rainbow Never Came is on view at the LSU Museum in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, through March 25.

This article features one of the artists participating in Art Crush, BURNAWAY’s upcoming auction and fundraiser, on Saturday, February 16 at The Factory Atlanta in Chamblee. Find out more about this year’s event—which includes a silent auction, interactive installations, live printmaking, and more— and purchase your tickets here.