Jeffery Gibson is having a tremendous year. After over a decade of steadily increasing national recognition, he was named the first Indigenous artist to serve as the solo American representative at 2024 Venice Biennale, prepared and opened a gigantic installation at Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art (MASS MOCA), and found time for smattering of gallery shows. It is Atlanta’s great fortune that the Zuckerman Museum of Art is among those institutions hosting a Gibson exhibition in this particularly formative year.

A small but comprehensive traveling survey show, Jeffrey Gibson: They Teach Love, from the Collections of Jordan D. Schnitzer and His Family Foundation, is an excellent opportunity to see some canonical works of Gibson’s oeuvre from the last fifteen years. As the name suggests, the exhibition is curated exclusively from the private collection of early Gibson champion Jordan Schnitzer. Exceptional examples from across the artist’s multidisciplinary practice are clustered in two rooms including assorted sculptures, photographs, prints, paintings, and garments. The works of Gibson’s critically lauded and Smithsonian-commissioned performance piece, To Name Another (2019) are mounted in a theatrically staged finale in the last room.

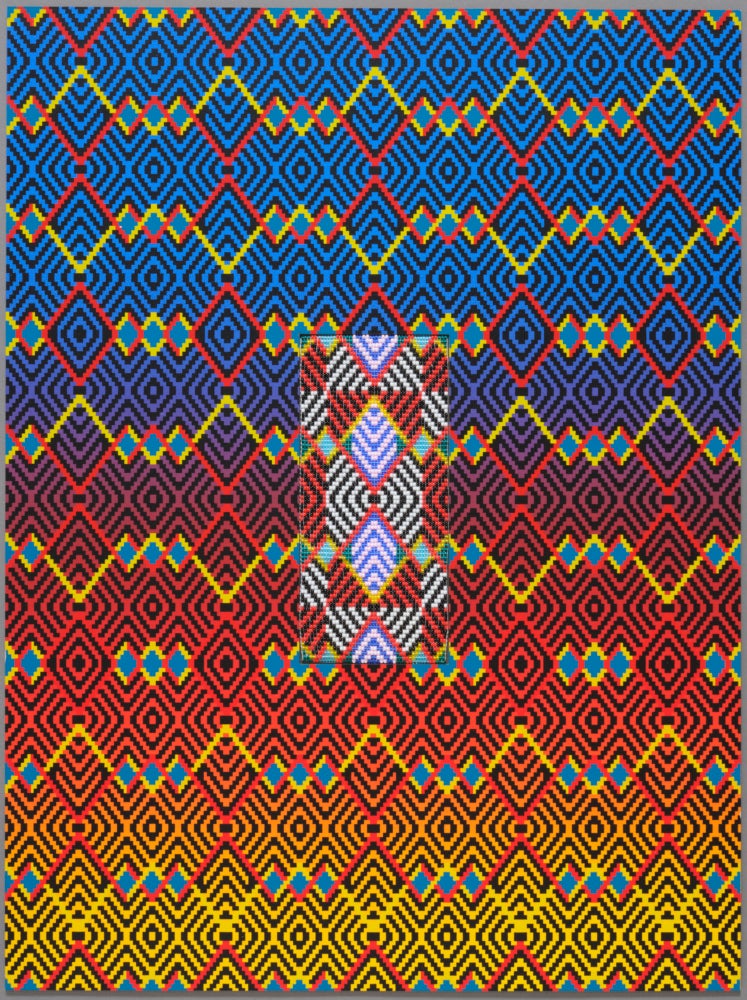

Two-dimensional works and sculptures alike display layered, sumptuous textures in beadwork, fabric, and pigment, all of which are rendered in his signature palette of bright, kaleidoscope colors. Without exception, Gibson’s work, in its vivid, tactile saturation, is rich with simple visual pleasures. But it is the work’s consumability that underscores most forcefully the artist’s incredible skill in collaging, a technique he uses to describe both his material and philosophical practice. All I ever Wanted, All I ever Needed (2019), is one in an ongoing series of beaded punching bags. Hanging as it would in a gym, the bag is transformed by a muted rainbow fringe and a jingle bell skirt. The body of the bag is wrapped in intricate beadwork of geometric patterns and a quote from Depeche Mode’s, Enjoy the Silence (1990), all rendered in distinctly Ellsworth Kelly-esque colors. In All I Ever Wanted, Gibson collages together his formative influences in a way that eschews flattening. Gibson is a citizen of the Choctaw Nation and of Cherokee heritage with an MA from the Royal College of Art, and grew up partially in South Korea and Germany in the queer club scenes of the early 90s.

While the references for the details in All I Ever Wanted may be obvious, they also slip and collapse into one another, shifting based on the viewer. The palette of the fringe skirt can be Kelly colors or the iconic queer rainbow as well as a reference to brightly colored powwow dresses. The slippage is precisely the point—this single work is a collision of culture, technique, and imagery, which folds up into a distinct, challenging, and gorgeous new totality. By setting the traditional elements of fringe and jingle skirt to dance to Depeche Mode, Gibson re-contextualizing the garments within pop culture and in doing so reminds the viewer that Indigenous practices are contemporary practices, not something relegated to the past.

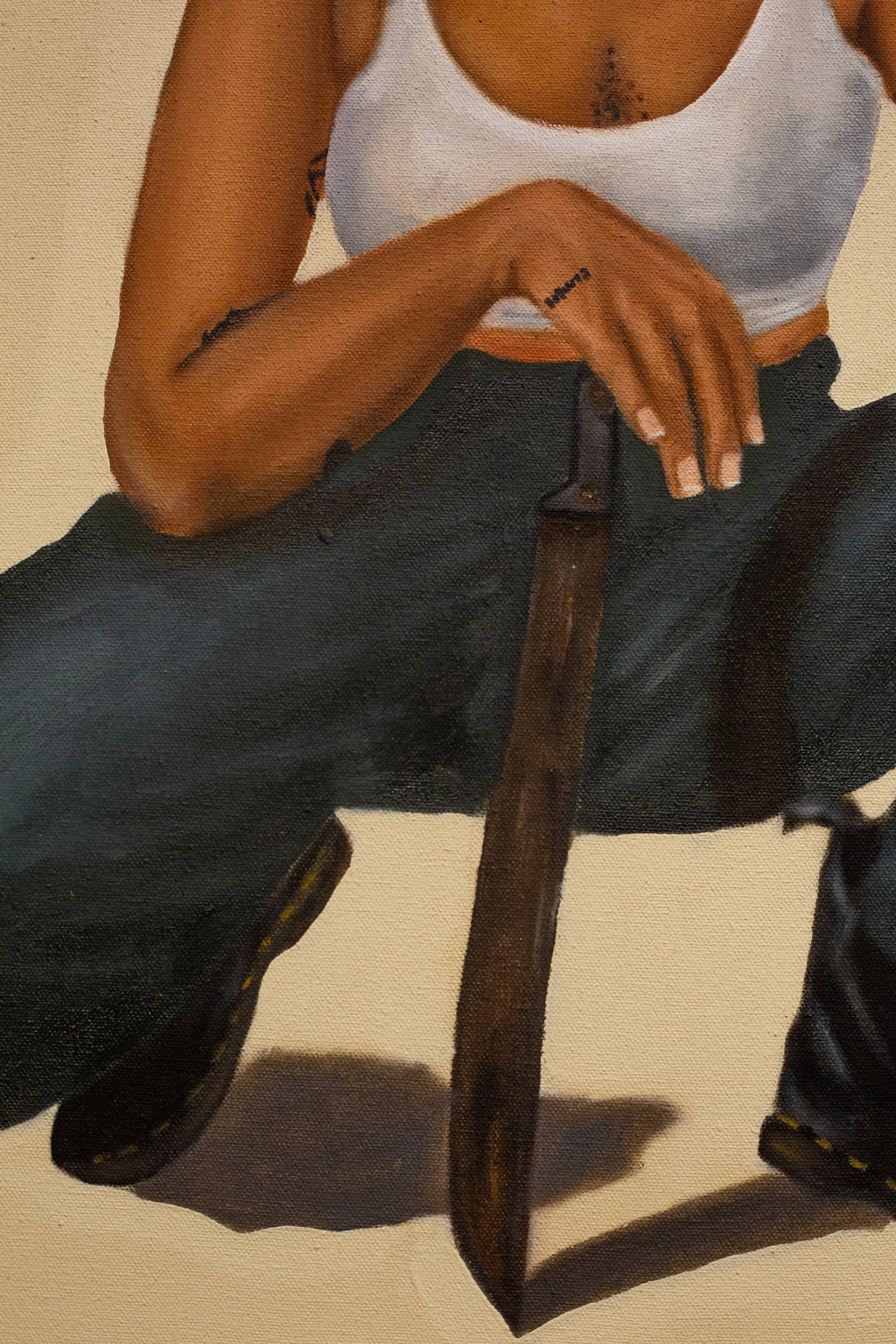

One work stuck with me for weeks. Stand Your Ground (2019), is comprised of two elaborate and monumental robes with fringe sleeves that hang from the ceiling, like silent sentinels. Not perfectly identical, each garment is a long layered skirt of many different types of fabrics, capped by a bodice printed with the repeated phrase “Stand Your Ground”—a reference both to the law in thirty-eight states which provides coverage and justification for racist violence including the murder of Trayvon Martin, and rallying cry against the incursive forces of the state and economic oppression which continues to eat in to the sovereignty and land rights of Indigenous people. As if to provide an example, the front of each skirt also includes the phrase “Tribes File Suit to Protect Bears Ears” layered and interspersed between sequins, and garish polyester panels often found on a dance floor. Without motion to shift and resettle the fabric, other phrases are deliberately unclear. From the back, the robes are constructed from handmade quilts and washed out nineteenth century photographs of Indigenous people mixed in with stock photos of white women in feathered headdresses. Should people put on Gibson’s robes, they would become a giant, with history at their back, while their chests led the way to an exuberant and hard won future.

It is impossible to describe all of the details, to consider all the messages, or to see all layers embedded in They Teach Love—I have said nothing about the fascinatingly complex relationship between western expansionism and consumerism and Indigenous craft, which underscores nearly all of Gibson’s work. But the challenge in conveying the whole of Gibson’s work is what makes it so compelling. Each object has multiple vantage points for recognition, combining to create a more holistic understanding of cultural presents and historical origins while growing one’s awareness of what might have been missed.

In every work from Gibson’s materially rich rainbow emerges an iconography that recontextualizes and celebrates the overlap in history, cultural specificities, and shared joys, collapsing hierarchies of belonging.