As is recounted in the epic Homeric poem, it took the Greek hero Odysseus ten wandering years to return home to Ithaca after the end of the Trojan War. The exhibition “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2017,” on view at the Met Breuer in New York through December 2, similarly presents the artist’s life as a personal voyage and widely cosmopolitan journey. Born in 1939 in Bessemer, Alabama, (famously known as the home of self-taught artists including Thornton Dial, Ronald Lockett, and Lonnie Holley), Whitten became a civil rights activist as a young Black man growing up in the segregated South. Until his death at the beginning of this year, he lived in New York City and regularly spent time in Greece. “Odyssey” brings together forty of Whitten’s sculptures—which have never been assembled in such a large number and presented publicly—deftly merging associations with African American history, African sculpture, and Greek mythology. Whitten is known as New York-based artist who brought politics and history into conversation with abstract painting, but here it is his deeply personal wood carving practice that enriches how we can see his better-known paintings.

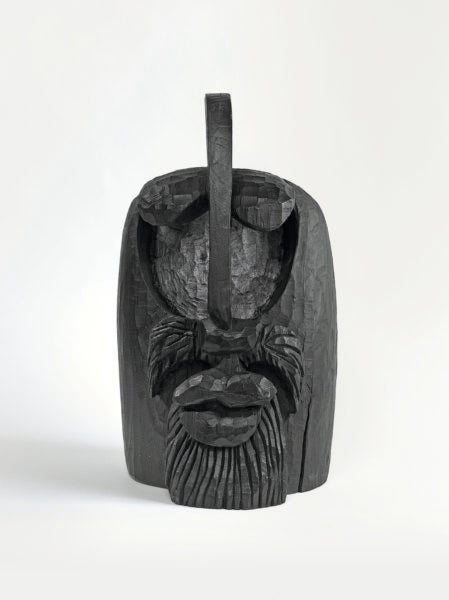

In 1960, Whitten left the racially charged politics of Alabama to focus on studying and making art in New York, although the content of his art often retained a political charge. His early carvings from the 1960s and 70s draw on both Southern folk traditions and traditional African sculpture. Like many of his generation, Whitten explored African history and culture with the idea of reclaiming a distant heritage. He visited the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Brooklyn Museum to view their collections of African objects. Carving became a tactile means for him to better understand what he called the plasticity of African sculpture. With its crested top, Whitten’s sculpture Jug Head II recalls the design of African masks, but its title and handle also speak to a tradition of ceramic face jugs created by enslaved African American communities in the South. These reference points are made explicit by examples of face jugs and African sculptures displayed alongside Whitten’s work at the Met Breuer. The objects were selected from the Met’s collection based on conversations with the artist about specific works from which he drew inspiration. What is astounding, even at the outset of his engagement with carving, is the skill of Whitten’s craftsmanship and the delicate balance he brings to rough assemblages composed of items such as nails and bottle caps, in addition to wood. Using these forms suggested a political message, perhaps more legibly valorizing African and Black American culture than Whitten’s abstract painting did in this period.

African sculpture was not merely a formal influence on Whitten; he took the symbolic power of its traditional materials and purposes seriously. Whitten’s sculptures often suggest protective and empowering functions similar to those associated with Kongo power figures from Central Africa, an example of which is on display in the exhibition. The sculpture The Guardian III, For Jack overlaps abstracted mulberry wood forms reminiscent of a blade and sheath, which are partially wrapped in blue nylon fishing line. (Whitten was, among other things, an avid fisherman.) The artist also made similar sculptures for his wife and daughter, Mary and Mirsini. Like traditional African power figures, each contains a secret object in its core. Kept in the home, these three works underline the fundamentally private nature of Whitten’s sculptural practice.

Yet a shared concern with materiality unites the sculptures and paintings on view, such as works from Whitten’s Black Monolith series, which pays homage to important Black figures in American history such as W.E.B. Du Bois, James Baldwin, and John Coltrane, in works comprised of small cubes. Whitten made these cubes by drying layers of acrylic paint and organic matter—such as herbs, ash, salt, or molasses—and breaking these sheets into pieces that he embedded on the picture plane like a mosaic, occasionally also including other found objects. By setting the cubes at angles, Whitten created glittering, tessellated surfaces on these works. This innovation speaks to how easily the artist assimilated all the products of his environment into a vision where each material element bears implied meaning and social significance.

Whitten travelled to Crete with his wife in 1969, discovering in Greece a landscape that resonated with his memories of Alabama. The pair would eventually buy a summer home there, where Whitten set up a woodworking studio with an exposed front sheltered under a fig tree. This manual mode of working—different from the paintings he was making with an increasingly complex set of homemade instruments in New York—opened up a different creative mode for Whitten. Ancient Cycladic and Minoan forms began to speak with African sculpture in his mind, and the titles of his works begin to reference Greek myth.

The 2007 sculpture The Death of Fishing operates across these multiple registers. The belly of a wooden form reminiscent of floating boat is filled with bones, net, lures, and hooks. The work’s title speaks to the dying fishing industry in the Mediterranean, something Whitten knew of personally from his active fishing on Crete. At the same time, the boat, suspended with fishing wire from a smaller knob that is slightly bent forward like a dipped head, recalls the silhouette of a lynching victim: the death of the fishing industry is overlaid on the image of a hanging Black body, a solemn reminder of the traumas of American history.

In his essay “Why do I carve wood?,” which is included in the exhibition catalog, Whitten writes, “My years of carving wood have been the single most important influence on my paintings.” Whitten’s sculptures help bring the artist’s engagement with materiality and craftsmanship—which, of course, can also be seen in his paintings— to the forefront of the viewer’s attention. The encrustations on the sculpture Gray Matter, made from sawdust and glue with Whitten’s self-reliant inventiveness, enliven the surfaces of the smooth mulberry wood and simple marble base. The uneven yet balanced adornment corresponds to the organically spreading patterns in Whitten’s painting Atopolis: For Édouard Glissant, which shows silver and lavender layers shining across its surface. Atopolis resembles an aerial view of a city at night, even while the Greek words of the title translate as no – place. Whitten dedicated the work to the Martinique-born French theorist Édouard Glissant, who wrote about creolization, the mixing of cultures. Cosmopolitan is a word which has, at its roots, the notion of being a citizen of the world, and the exhibition “Odyssey” demonstrates the richness of the cosmopolitan position, one that draws on a several varying places and cultures. For Whitten, constructing an atopolis—a no-place built upon deep engagement with many places—was possible because of the distinctly cosmopolitan world he inhabited.

The exhibition “Odyssey: Jack Whitten Sculpture, 1963-2017” is on view at the Met Breuer in New York through December 2.