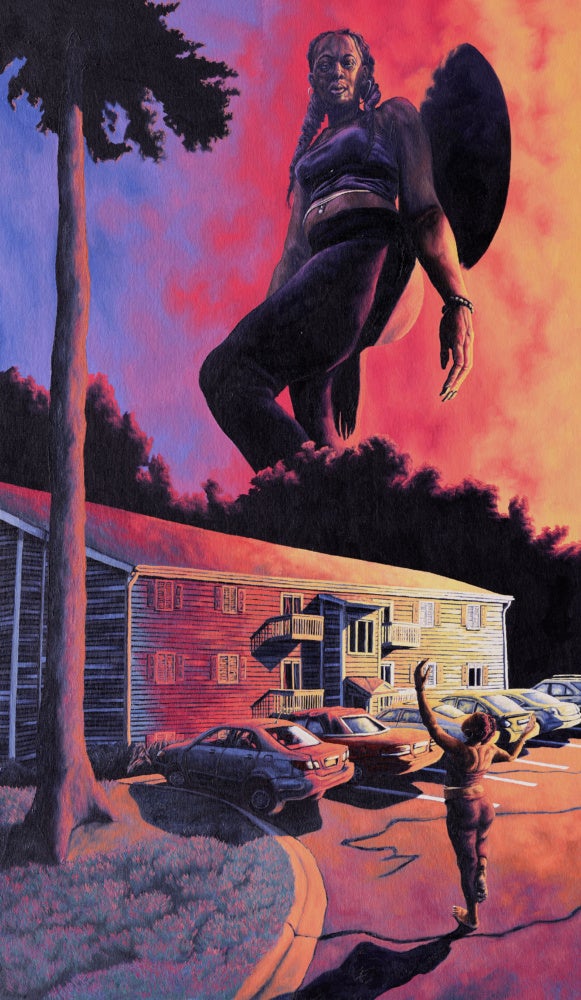

In his home studio in Stone Mountain, Georgia, narrative painter Tim Short’s distinctive practice centered on oil paintings offers an exploration of Black identity through imaginative, atmospheric art styles. His series For Da Folks exemplifies this approach, transforming intimate family moments into narratives imbued with cosmological and celestial imagery. By employing grandiose color schemes and dramatic lighting in his works, Short subverts traditional associations of lightness with divinity, instead granting a metaphysical iconography to Blackness.

The following conversation was edited for length and clarity.

Tyra Douyon: In your For Da Folks series, you describe your creative vision of Blackness as an “energy source” that opens pathways to alternate universes. How do you translate that metaphysical concept into visual form—through color, composition, or symbolism?

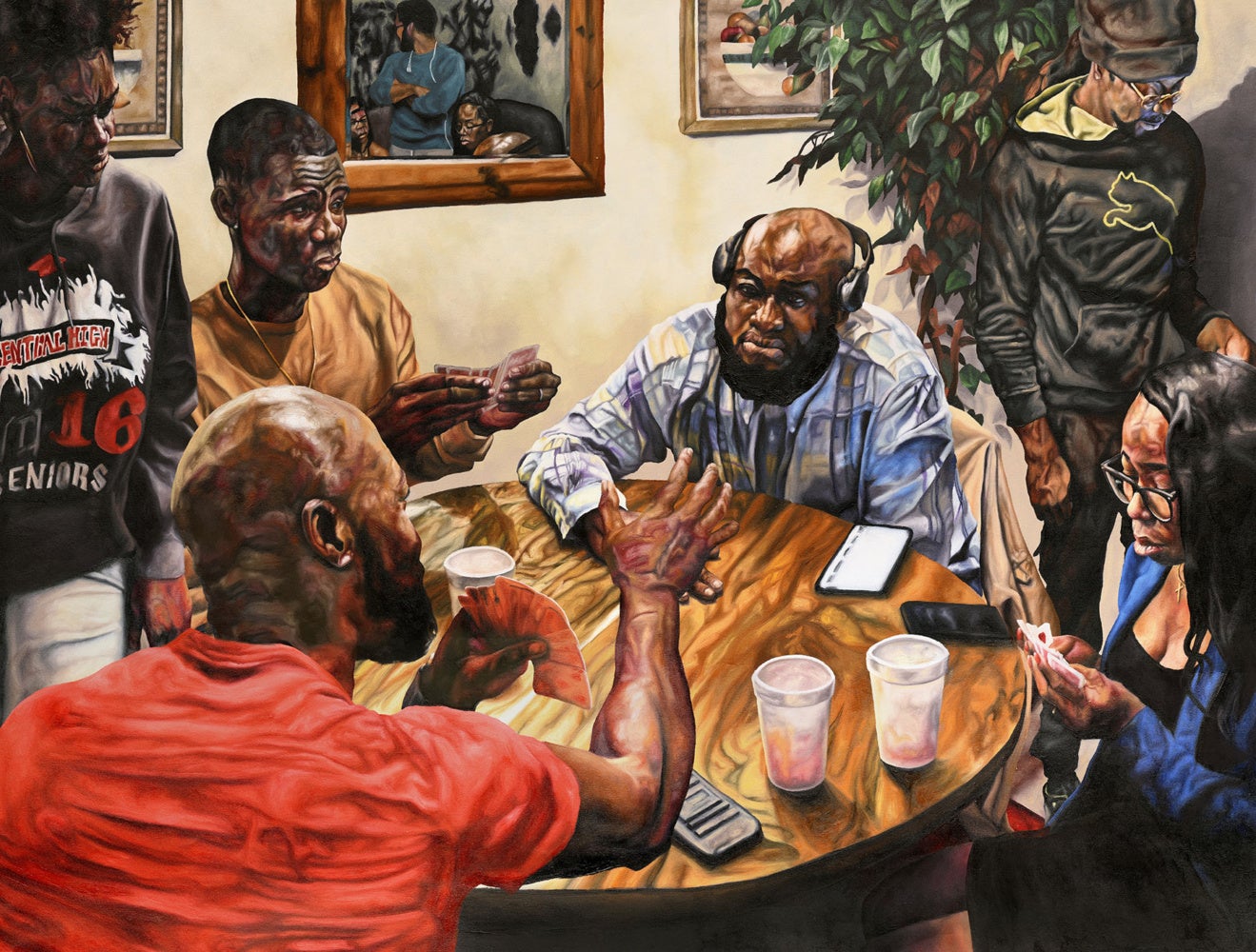

Tim Short: Blackness is existed within and it’s a tangible entity that can be embraced, moved into, or even left behind. Describing what I want to say about Blackness and what it means to me is how I’m conceptualizing these different things. It comes off as ritualistic—interactions with family or people who are close to you. Through those rituals, metaphysical and surreal things occur. That’s what the content of the work is: subjects being in places that are familiar to Black viewership. With that familiarity, the spirituality of it all just exudes itself and envelops the subjects in a way that determines themselves through Blackness.

I don’t necessarily feel like the work is a refutation of anything so much as it is an acceptance of something. Diametrically, it is moving away from white sensibilities or restrictions placed on what Blackness is or what Blackness can be because of the white gaze or limiting ideas or of being forced to make whiteness comfortable. I would say, if I’m refuting anything, it would be those things. Even when the work feels off-putting or challenging, or darker, as some people have come to talk to me about, I’m actively trying to say something enlightening to myself about Blackness.

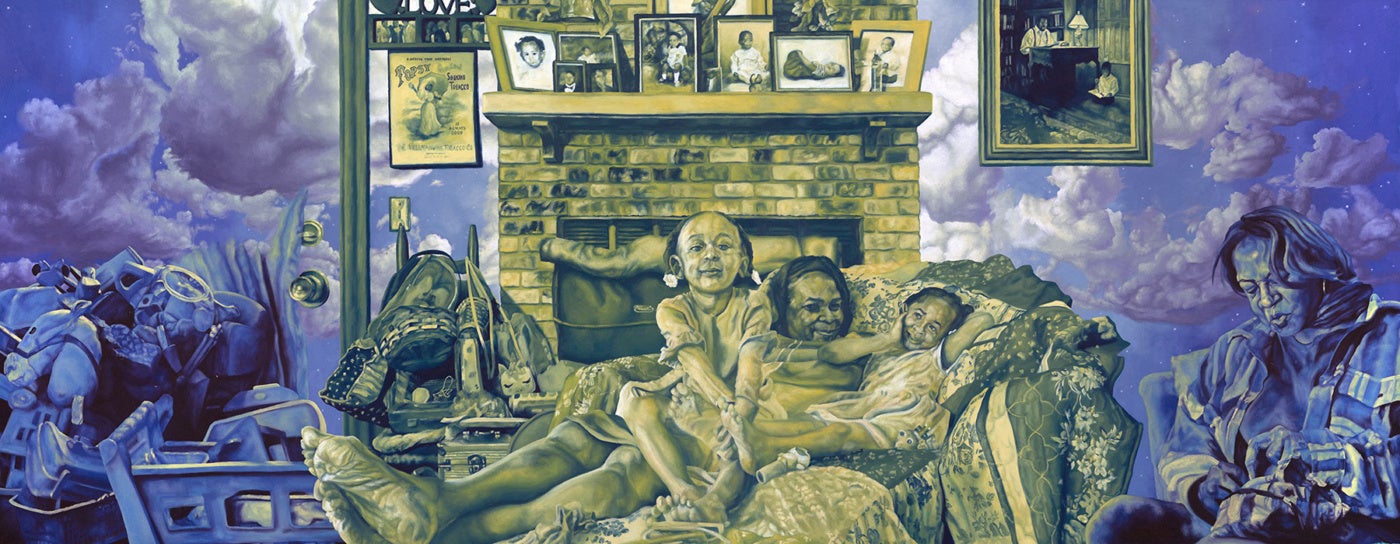

TD: Pieces like The Fish Gives Birth to Herselves (2017) evoke cosmic or mythic dimensions, with a deep analysis of self at the center. How do you balance personal storytelling with these expansive, speculative narratives?

TS: Whenever I get around people who I want to paint, I want to put a piece of them into the work as well. I look at paintings I do of other people as collaborative. They are bringing themselves, and I’m exploring them and their creative potential as a being of arbitration, action, and agency. That’s how I’m approaching the work. It comes off as divine or godly because I want to show love and appreciation for those people. In that love, I want them to be an agent of their own purpose and will, and of their own story too.

In The Fish Gives Birth to Herselves (2017), it’s a portrait of one of my best friends. Her name is Makeda and she’s an artist. The art you see featured on the walls in the painting is actually her work. She’s being raised up as a master, architecting this presence as an authority through her artwork. Through the painting, I’m trying to build metaphorical imagery to relay that message.

TD: You’ve cited various influences ranging from artists like Kerry James Marshall, Toyin Ojih Odutola, Jordan Castee, and Barkley Hendricks, to anime and manga, Biblical imagery, and Pink Siifu’s song titled “Gumbo’! 4 da Folks, Hold On.” How do these diverse inspirations converge in your creative process?

TS: I would say all those sources of inspiration connect and create with narrative. I’m listening to a lot of jazz, jazz fusion, and a lot of rap. I like Pink Siifu, Mike, Mavi, Khia, you know, a lot of different artists who just build narrative through sound in a raw way. That is inspiring. I’m in a book club now and have been reading a lot of books and manga. It’s all about training yourself to engage with long-form content and glean as much as possible from it and paint in the same way. I want to be able to really say that I am the authorizer of narrative, the agent of narrative, the arbitrator of narrative, the creator of narrative.

TD: Many of your paintings depict Black individuals in surreal or celestial spaces as divine beings. How do you see this blending of spirituality and visual storytelling contributing to conversations around reimagining Black identity in contemporary art?

TS: I would just like the work to think of Blackness reverentially, to build a desire to be connected to it and to flow towards it for Black people. As far as the divinity, it’s about encouraging self-determining individuals. When you are self-determining, there’s a power there, there’s a responsibility there. That is what I want the work to say. Power and enfranchisement are always going to be linked to Blackness. In thinking more communally, I want the work to aid rather than harm.

TD: Your recent exhibitions encourage viewers to slow down and investigate, creating tension between curiosity and uncertainty or discomfort. Is this interplay something you intentionally build into your work?

TS: No, I don’t think so. I don’t think I approach painting like, “Oh, they’re gonna be scared.” I don’t create with the intent of terrifying someone. I would like to think all of my paintings are cool. I don’t want to treat my viewers like they are not as smart as me. Anytime I create, honestly, I’m doing it with the idea that this might be a little weird, but this is what I like. Maybe they’ll like it. That’s great if they don’t, but maybe next time, they will.