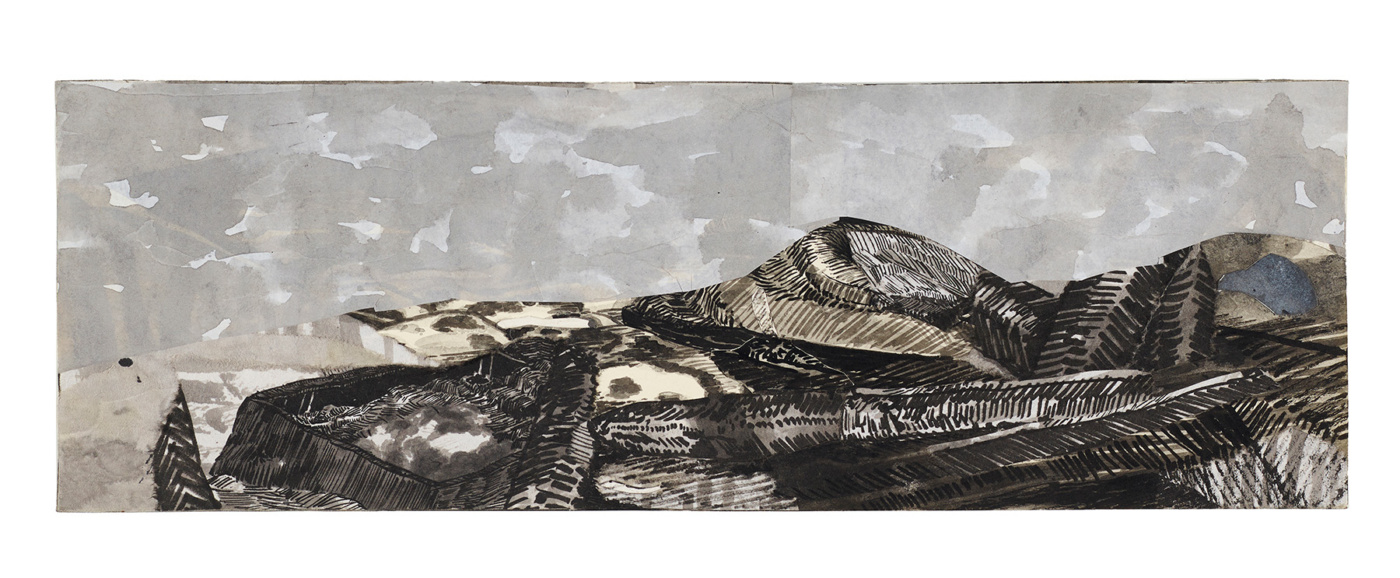

Mariam Aziza Stephan is a first-generation Afghan American painter based in Greensboro, North Carolina. Her work often portrays abstracted landscapes as a metaphor for and an aggregate of sites of upheaval, destruction, or no-go zones, with her depicted locales, as she says, “carrying the scars of their histories.” She is the recipient of a 2018 North Carolina Arts Council Fellowship, a Fullbright scholar, and currently a professor of painting at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro.

Having shown her work extensively in the US and abroad over the years, Stephan was recently featured in A Montage That Tells a Truth in This Bound Flesh, a pop-up show at the University’s Greensboro Project Space. The exhibition presented Stephan’s newer paintings and drawings in dialogue with poems by writer Julia Johnson. Both creatives highlight the planet’s enduring struggle against centuries of exploitation in their works, with their ongoing conversation representing urgent but, in their view, often cyclical concerns.

The following is distilled from a lengthy and wide-ranging conversation I had with Mariam in her Greensboro studio. We discussed how to chronicle loss and uncertainty and the importance of abstraction and ambiguity in both of our works. It has been edited for length and clarity.

Paul Bright: You just closed a show at UNCG’s project space. Can you tell me a little about the work you had there?

Mariam Aziza Stephan: I guess I just wanted to get the work out of the studio, have fun with low stakes, low pressure, be able to see it. The other thing is that I have been working with a poet, Julia Johnson. We’ve been talking about what are digital and performative ways that we can reimagine or visualize her poems so that they mirror the same degree or kind of fracturedness present in [my] drawings. And so that encapsulates what we did.

PB: Going back to this from your website, the work is a chronicle of loss. How do displacement and migration align with the stressed and degraded environments that your work expresses as much as it depicts?

MAS: I think the landscape itself, as my chosen imagery, is absolutely meant to be an embodiment and a visualization of those states.

Both literally and metaphorically, how can I represent the disjointedness, the dislocation, and what it means to have the ground potentially taken out from underneath you? My father was born and raised in the former East Germany. When the Russians were given the territory after World War II, the very same piece of land was not the same land that it was the day before.

We’re seeing this with territorial fights all over the world. What does this land mean? And you can’t just change its name. It doesn’t just disappear. It’s like, I’m still standing here…What does that disorientation feel like? And then, how do you translate a feeling? With this very limited formal vocabulary, how do I try to mash up spaces?

PB: Your works function that way in terms of the forms you use and the degree of abstraction. You’re getting a certain specificity and a certain level of abstraction, and the structure is always disquieting. It’s not like you ever feel like you’re on stable terrain.

Your dad grew up, or became, an East German. Did you grow up in the States?

MAS: Yes. [My dad] had met my mother–who’s from Afghanistan–in Hamburg when he was going to medical school. She was studying to be a nurse in the same school, but when he was offered a residency in Pittsburgh, they were, like, “Absolutely!” Even though they were both going to be [learning] English as a second language, I think that that was something that he took a lot of pride in, that they had taken that leap together.

PB: They met with two different stories, but this one was theirs together.

The idea of “landscape” and how you have found abstraction–in its degrees–to be the vehicle for their metaphoric excursions…would it have been possible to achieve the same feeling in the landscapes if they had been more depictive?

MAS: From a really young age, my interest was in the emotive qualities of art. I ask myself sometimes, those little kind of nuggets of representation, are they an anchor or are they a foil?…or both?

The physicality of the materials themselves speaks to the condition, the psychological condition, and an ephemeral quality that’s both tangible and fleeting in nature. I think that’s why abstraction is the most important thing, I would argue, in any painting or drawing; it is nothing if you don’t have abstraction.

PB: It’s funny because a lot of people say, “Oh, that’s really art,” where it approaches the verisimilitude of a photograph. But that’s just all surface compared to the structures that should be underneath all of it, which is why it’s nice to have this dance between a depicted thing or a hint of one as well as the structure of abstraction.

MAS: A part of me has always thought about [the image surface] as its own stage and terrain. That mark can dance from here to here to here and transform itself across the page. When you think about the syncopation of marks, and the rhythm of long and short marks, it’s always out of musicality and a dance-like rhythm.

PB: They are arenas. It’s like a plane on which you’re doing things; it’s the space that you inhabit with action.

MAS: I have found that you can have complex things happening simultaneously. I think that has ultimately been my interest: can I invest as many ambiguities or paradoxes into an image as possible so that it feels like real life…

PB: Or the spirit of it…

MAS: …even if I’m not depicting, not copying it?

PB: Ambiguity is something that really interests me in art. Unfortunately, in recent years, it seems there’s been less of it…

MAS: Absolutely.

PB: …but it’s one of the strongest things in art’s toolkit to help you make sense of things. The ability to read more than one thing at a time.

I had another part of that question, of expressing a heightened awareness of nature. Obviously, your group of small works and your large drawing, which we’re looking at here, both express that awareness in different ways.

MAS: I am concerned with [nature] becoming a metaphor for our psychological state, like that of a collective consciousness. I have said that the landscape is an entity, a body and therefore has a persona to me that’s as complex and as fluid as any one single person.

How do we experience the world? What are we an aggregate of? Living and feeling and recalling and sensing. Those are exciting things to sit in.

I think the only answer I was desperate to have as I was growing as an artist was: When will my practice reach a place where I feel like it’s an endless well? A feeling of, wow, it just keeps turning into something else? [Now] it just keeps rolling, and every time it rolls, a new thing opens up, or a new image unfolds into twenty other versions of itself. It’s sort of crazy because I don’t feel done. I could sit all day and work with this same limited palette on these small drawings. Actually, I think that’s why I forced myself to go outside and breathe deeply.

View more of Mariam Aziza Stephan’s work on her website, mariamstephan.com/