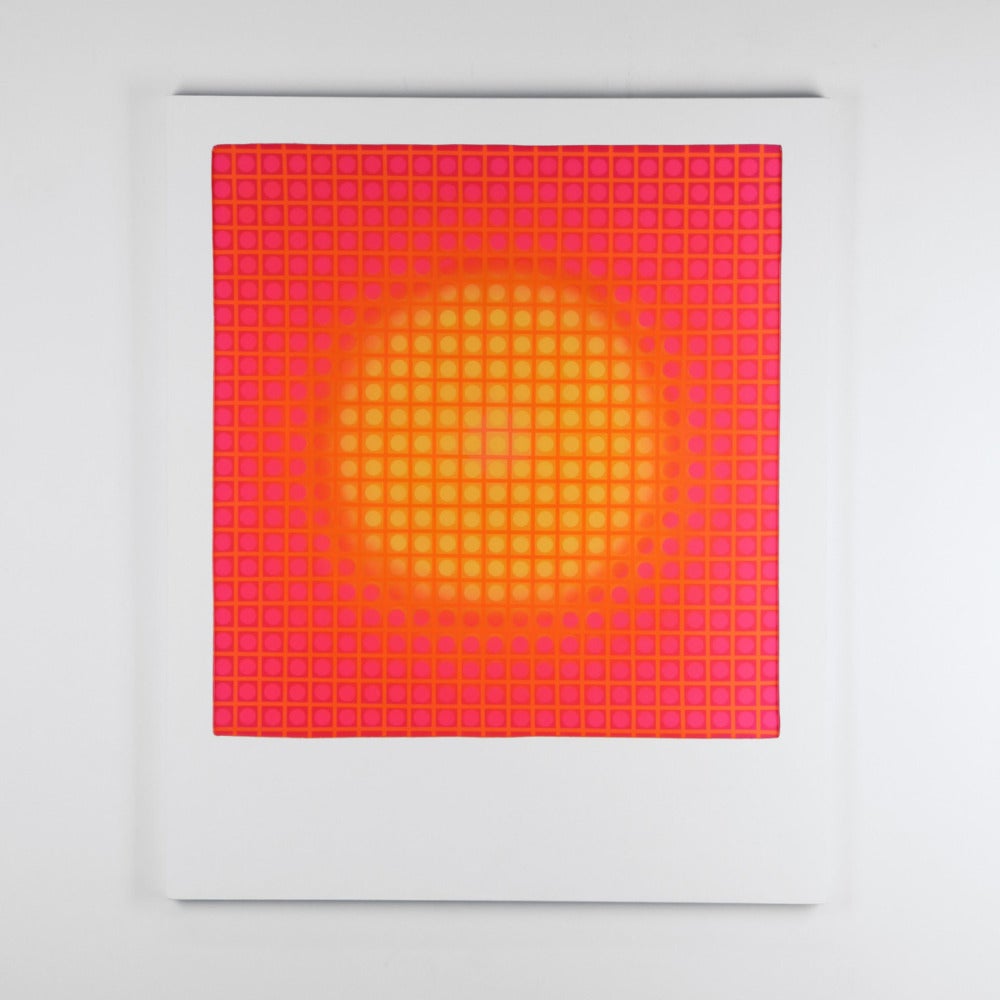

With an endearing air of bewilderment, Letitia Quesenberry describes her approach to art-making as ambiguous intent with “shifting levels of subtlety that interrupt automatic ways of seeing.” And while her pleasant persona is clearly perceptible in her work, her attempt to define it is uncomfortably challenging. Like her art, Quesenberry resists categorization by default, preferring to linger in the intangible and enigmatic to produce evocative and wordless encounters. By harnessing color and light in ethereal and meditative rhythm, she produces a visualization more than a visual. In essence, her work is about the act and experience of seeing.

While formal abstraction is predominant within her oeuvre, that doesn’t quite describe it either. Hiding under a cloak of mystery, Quesenberry unequivocally accepts all interpretations, skirting labels in the process. Yet, as a queer woman, she also acutely recognizes and accepts the significance of identification. This makes sense in a realm where opacity and translucency are intentional tools as much as metaphors. Her series wear unabashedly poetic titles such as How this Came to Be, a reference to the psychedelic Folk Rock song “Apocalypse,” by White Magic. The excerpted lyrics seem to point to the political disintegration of now. Others like Union of Opposites and As of Yet beg meditative introspection with subtle hints at life’s grandiose questions in a more nebulous timeframe.

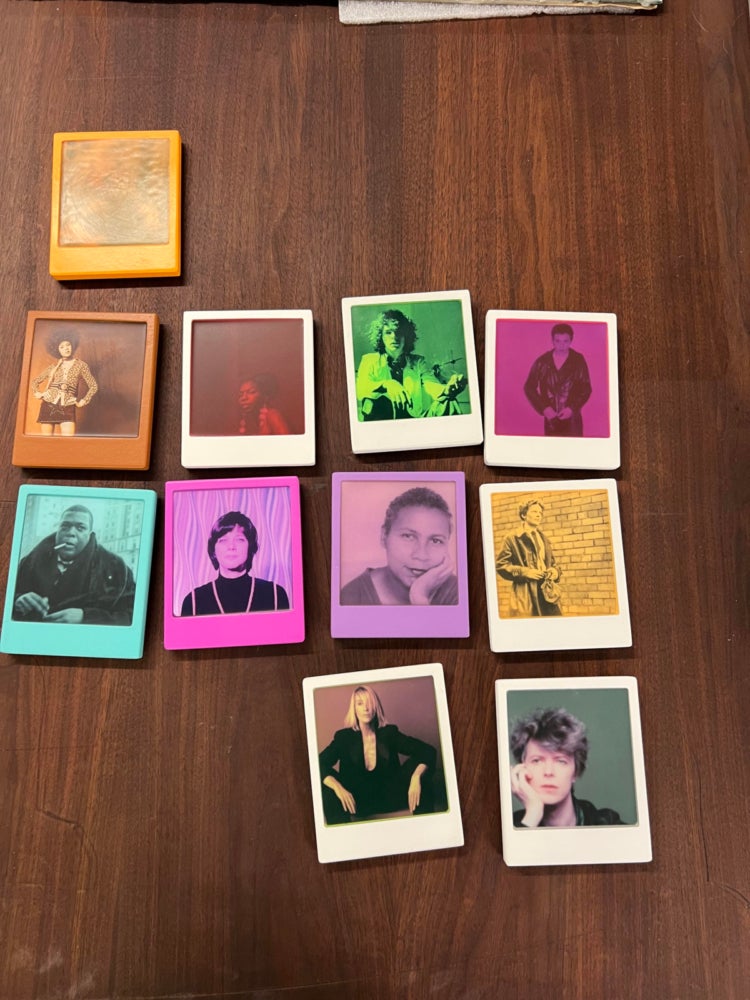

She organizes her output into groups of visual experimentation, traversing formats and shifting media, predominantly delineating by scale. Hyperspace and BLSH (pronounced “blush”) utilize similar techniques, distinguished primarily by the former’s electrical and LED circuitry. The series Little Darlings, in development since 2014, are 6×5 inch Polaroid-esque snapshots of iconic reverence. Discernibly famous figures, like Nina Simone and David Bowie, alternate with murky silhouettes and the recognizable faces of deceased loved ones. Little Darlings explores another kind of seeing through remembrances. As a whole, her body of work is comprised of iterations, markers of her evolution in both process and technical discovery. She toggles back and forth between all of them, working on several pieces simultaneously, perpetually interrogating the act of observation.

Most of all, her work quietly screams to slow down and look.

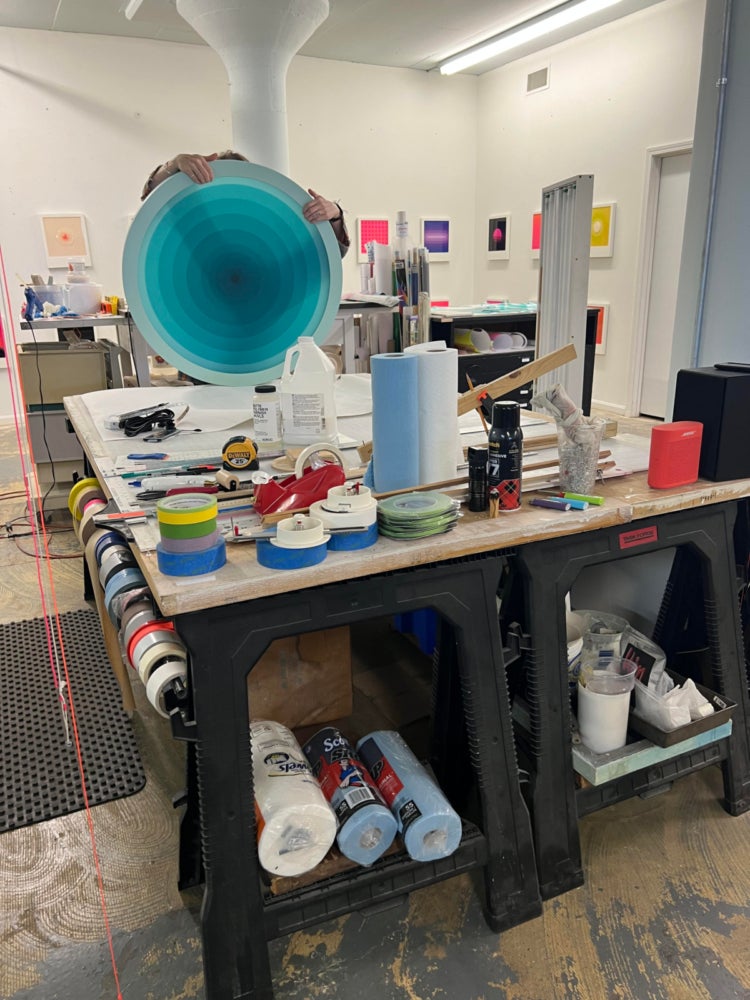

What follows is a compilation of interviews I conducted with Quesenberry, beginning in spring 2022, in Louisville, KY, where the artist lives and works. Her studio is in an industrial building shared by seven other artists and an architect, portioned into informally occupied lofts. There is very little natural light, one rough bathroom, and no public access. Upon reaching the second floor, her vibrant pieces spill out into a shared common area. Through a doorway, other saturated arrangements punctuate the white walls. The artist’s space is organized and lightly powdered with sawdust; she does the heavy-lifting and most of the carpentry, preferring to build the majority of framing herself. Besides the weekly residency of Agnes, her and her wife Amy’s rescue dog, she is mostly alone in her daily retreat. But, the walls are uninsulated, the floors concrete, and the sound of her studio mates’ music or conversations inevitably penetrates the space. She enjoys how life seamlessly spills in, finding something “soothing and reassuring in the banal.”

Jodie Bass: You use a variety of materials in your process — tape, mylar, mica, resin. More recently you’ve incorporated coal dust. How did you come to use it, does it have any meaning other than its visual properties?

Letitia Quesenberry: Coal slag is a recycled by-product produced by power companies. My cousin had a bucket of it in his shop (for use in sandblasting) and as soon as I saw it, I knew immediately I had to figure out a way to use it. I was drawn to the sparkle and texture. The other connotations are impossible to ignore, especially in Kentucky. Most people have an immediate reaction to coal: either that it is very good or very bad, which is interesting. In using it, I wanted to draw attention to how beautiful it is, to increase respect for the materials that we depend on so much.

JB: Does repurposing hold value for you. If so, in what way?

LQ: Absolutely. I come from a long line of creative savers. I find it nearly impossible to throw things away. I have discard piles of things I call “remnants.” These are the artifacts, leftovers, and failed experiments of things I have made/am making: scraps of wood, odd pieces of color film and plexiglass, bits of resin poured into impromptu molds, buckets of crushed pyrite, blobs of dried latex paint. It’s how the newest series Pacifiers came to be. I really take Corita Kent’s art department rules to heart. The last one is “SAVE EVERYTHING — IT MIGHT COME IN HANDY LATER.”

JB: Tell me about the installation piece with sound artist, Aaron Rosenblum, A Brief Elaboration of a Tube (2018).

LQ: That was in the basement of Spaulding University (Huff Gallery, 2018). It was ceiling height. I used the room to make the dimensions. It was about twelve feet tall.

JB: Is that the only time you’ve done something of that scale?

LQ: Probably. Unless you count what Robert Curran [Creative Director of Louisville Ballet] and I did.

JB: You’re referring to when you did the set design for the ballet? What does working in a larger, more immersive scale like that do for you?

LQ: It was a challenge for sure, but it was fun. I always feel constrained by the amount of time and the budget — limited by what you can physically carry out.

JB: Is engagement with your audience different when it’s perceived performatively? Does that dimensionality change your work at all?

LQ: I don’t think so. I’m trying to make work that is clear but not obvious. So no matter what the size, the main concern is for it to be interesting without smacking you in the face.

JB: Do you consider your work 2D?

LQ: Yes, because they’re mostly wall-based but they do kind of ride a line… Like this one project I did at Bernheim Arboretum. It was only up for three hours during one of the night events for Connect. It took all day to do. It was grueling — so hot. I used flashing barricade lights, set up along the bank of the lake to utilize the reflection, omitting vowels so you couldn’t really comprehend it unless you got far away.

JB: What did it spell out?

LQ: “Glmmr,” to be measured out in this bizarre way so it would read from a distance. [Glimmer was installed in 2013.]

JB: You say you like basic stuff, but your work is not basic at all; there’s so much nuance. Yet practical things like “dad beer” and having sports on in the background is really appealing to you. Why?

LQ: It gives room for anything to happen. I like parameters, but then whatever happens within them is left to chance or happy accidents, a kind of stumbling. For example, I started making light boxes and I got frustrated with the electronics and parts needing to be replaced. I mean, I love them and people recognize them, but I wanted to figure out if I could take what I learned and push it. They didn’t need light, so I started making those (pointing to a work of BLSH).

JB: That’s been for how long?

LQ: A couple of years. But I learned so much that I started making light boxes (Hyperspace) again, incorporating what I learned.

JB: How did your work become so physical?

LQ: For a long time I worked as a decorative painter, my job involved going into people’s homes and doing finishes. But I did my own work, too. I was drawing a lot and started making big surfaces with little drawings. The people in the drawings got so small that it was more about the atmosphere. I used wood, sometimes putting canvas over it, then plaster, burnished into a shiny surface. Then I would draw on it, embedding graphite in the layers. My shoulders suffered.

JB: Is Op Art [also known as Optical Art] something that resonates with you? Do you have any specific inspirations, artists or artwork?

LQ: Definitely, Carlos Cruz-Diez. There’s a whole school of South American painters from the 1960s that did kinetic work. Also painters like Bridget Riley and Julian Stanczak. I’m totally into them.

JB: Some of it is sculptural, mirrored, and three-dimensional, right?

LQ: Yes, objects. There was an exhibit I went to see at the Palm Springs Art Museum in 2017, Kinesthesia, curated by Dan Cameron. It had all these memorable pieces, including ones by Julio Le Parc and Jesús Rafael Soto. Seeing all this work in one place really shifted something in me. [We start to page through the catalogue from the group show The Responsive Eye exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, NY, 1965, which highlighted the new international art movement of Op Art].

But Cruz-Diez, man, I could just flip out on him a hundred percent all the time.

JB: What’s the material?

LQ: He made objects using strips of cardboard.

JB: And then it was painted?

LQ: Yeah. So, as you move across them, they do this flickering thing to your eyes. He made Chromosaturation rooms. Stand in one and the light is pink, but the longer you stand there, your eyes adjust and the color becomes less pink, gradually fading to white. Next, there are two adjacent rooms of different colors. Moving from one room to the next, you feel your eyes adjusting. Entering a room you know is blue or green, but your eyes are tumbling through the color. It’s so wild. It’s so great.

JB: That seems pretty manipulative in a way though.

LQ: It’s a perceptual experience. You can choose to not have it or to not engage, you could walk through and be like, “whatever, where is the art in this?” But if you actually slow down and allow yourself to experience it, it’s really effective and so simple.

JB: It makes me think of James Turrell.

LQ: Exactly like that. I want to grab people’s attention but how, really? It’s a seduction, making them want to look…

JB: How do you stay disciplined in working?

LQ: There are parts of the process that are really hard and painful, requiring more discipline. Some days I show up and sweep the floor because that’s all I can do, or sit on the couch and nap or read. It’s about being here and showing up….

JB: Every day, basically?

LQ: Pretty much. I take weekends off except for a few hours. During the week I’m unhappy if I’m here less than six or seven hours. Once I’m here, there’s really not much else to do, but do the work.

JB: What’s next for you, career-wise?

LQ: I’d like to have my work out in the world, not just Louisville, but in other places. If it could just find its place, where it needs to go.

JB: You mean you would like greater gallery representation and someone to push the work? That’s the structure, right? That’s how it operates.

LQ: That is how it works. But, I don’t like chit chatty situations. I used to try harder, but after the past two years, I really don’t want to do that at all.

JB: What has it been like preparing for this upcoming show in Denver? How is it different, if at all? Will you go to the opening?

LQ: I made some new work for this show [at David B. Smith Gallery]. A lot of the Pacifiers that were in Northern Kentucky are going to be in it. I’m showing with another artist, a really cool ceramist Linda Nguyen Lopez, so I am excited about that. It’s the same gallery I’ve shown with before, but that was during the pandemic, so I think I will get to go now. Amy may come with me, her niece lives out there.

JB: So you have three of your series in this show?

LQ: Yeah, I am sending a group of As of Yets, Anon, and Pacifiers, I’m just waiting on the art shippers now.

Letitia Quesenberry: Future Maybe is on view at David B. Smith Gallery in Denver, Colorado through December 17, 2022.