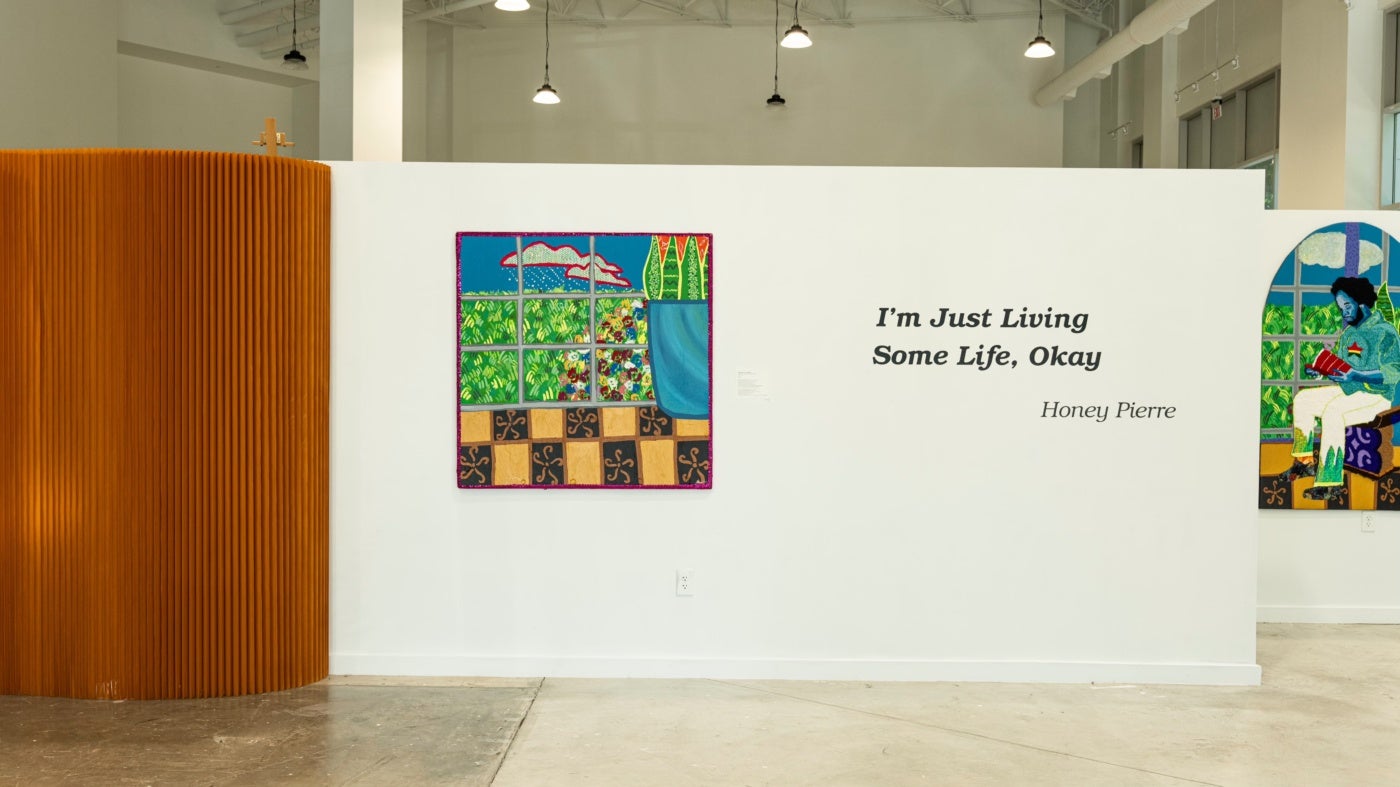

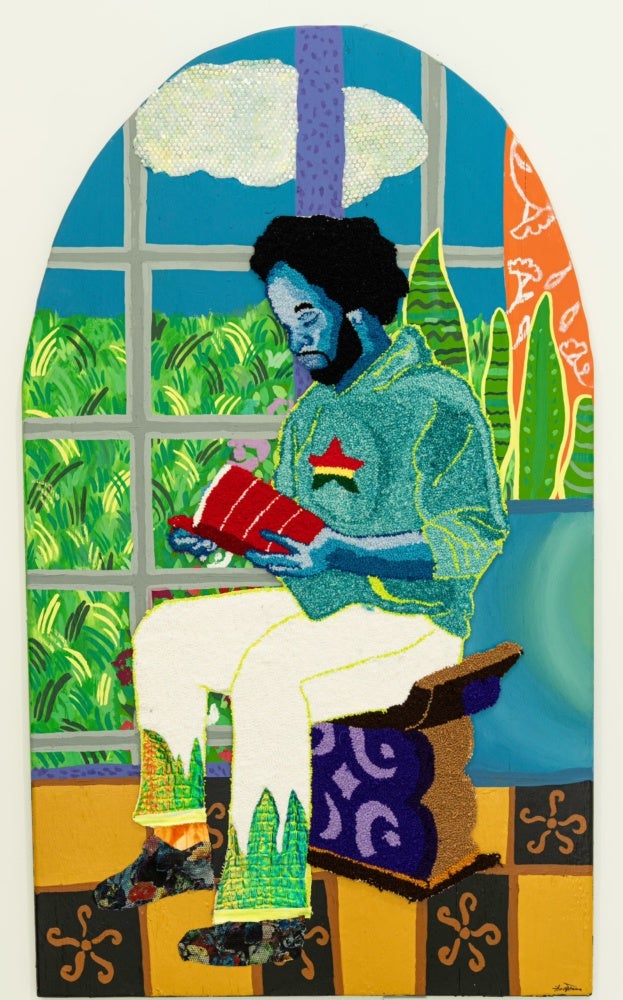

In her Atlanta studio, Honey Pierre creates richly textured portraits that center Black and Brown life in moments of softness, joy, and everyday intimacy. Using punch needle embroidery as her primary medium, Pierre weaves color, texture, and symbolism into scenes that reclaim rest and emotional presence as acts of quiet resistance. Working largely in vivid shades of blue, she reimagines the body as expansive, liberated, and beautifully whole.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Christal Reese: Your journey into the art world wouldn’t be labeled as conventional. How did you find your way into becoming an artist?

Honey Pierre: I didn’t go to art school and I joined the military right after high school. When I got out, I went back home to Cleveland to take a breather and figure out what I really wanted to do. I knew it would be something creative, but I wasn’t sure what form it would take yet. I’ve always loved tattoos, so I got an apprenticeship at a local tattoo shop.

Working on the body taught me so much that I still apply it in my practice today—how to see anatomy, how people pose, what movement looks like in real time. You have to really understand the silhouette of the body to place a tattoo where it will look good and move naturally. Learning that hands-on gave me a foundation that later translated into how I approach portraiture.

CR: How did punch needle come into the picture?

HP: It was during the pandemic. I have a weak respiratory system, so I couldn’t use oil paint or charcoal—the fumes and dust were too much. I was watching YouTube videos on how to make rugs and stumbled across punch needling. The second I tried it, I thought, “Wait, this feels familiar.” It mimicked the same motion I used when I was piercing. It was repetitive, controlled, and tactile. From there, I just kept going.

CR: Was there a moment when you realized it could be more than craft, that it could be fine art?

HP: Definitely. I watched an interview with Bisa Butler where she talked about adding fabric to her paintings before she fully moved into quilting. That clicked for me. I realized I’d already been incorporating fabric into my work without even thinking about it as a formal shift. With punch needle, I saw that it could hold the same emotional weight and presence as any painting or sculpture.

CR: What does your process look like now?

HP: I write first. Always. I start with what I’m feeling or what I want to express—sometimes it’s joy, sometimes grief, sometimes just stillness. From there, I sketch a composition, choose my model, and take reference photos. The punch needle part is slow and methodical. Thread by thread, loop by loop. Once the portrait is complete, I paint the background to pull it all together.

CR: One of the most striking things about your work is your use of blue for skin tones. How did that come about?

HP: Blue has always carried a lot of symbolism—people associate it with sadness, melancholy, or even detachment. For myself, it became a color of liberation. Growing up, people would use “blue” to insult us—to say we were too dark, too much, too other. I wanted to reclaim that, and so when I use blue, it’s not about sadness. It’s about vastness. It’s about beauty. It’s about refusing to be defined by someone else’s limited gaze. I use blue to make our presence undeniable and expansive.

CR: Your use of florals and vines seems deeply symbolic, too.

HP: It is. When my mom bought our first house, she didn’t worry about painting the walls—she went straight to the yard and planted a garden. That stuck with me. Nature is full of metaphors: growth, decay, rebirth. Florals and vines are a visual language for all of that. They remind me that we can replant ourselves and still thrive.

CR: What are some of the themes that show up consistently in your work?

HP: Joy. Rest. Intimacy. I think we’re in a new era where we don’t have to keep telling stories rooted in trauma. We’re allowed to just exist. I want to show people laying in the grass, being held, laughing with friends. There’s power in that. I think joy is a form of resistance.

CR: You’ve mentioned before that Atlanta really helped you find your artistic voice. What drew you there, and how has it shaped your work?

HP: I realized I had outgrown Cleveland. I needed a new environment that would allow me to grow creatively, and Atlanta just kept coming to mind. I’m glad I made the move—especially because when the pandemic hit, Atlanta was one of the few places where artists could still work and exhibit. Being in Atlanta gave me a sense of community that I hadn’t experienced before. During the shutdowns, I wasn’t doing exhibitions—those were all closed—so I started doing public art projects, which connected me to people in a new way. Atlanta’s Black art community is tight. We really show up for one another. That support, that feeling of being seen, made me want to create more work about gathering, about rest, about connection. It helped me move away from trauma and focus on the quieter, realer moments of life.

CR: The people in your portraits—are they people you know?

HP: Most of the time, yes. It’s usually friends or people I’ve worked with before. Once I have the emotional tone or story I want to tell, I think about who can help me bring that to life. I take reference photos, then sketch, then begin the punch needle process. It’s all very intentional. These are real people and real feelings.

CR: You’ve called this moment in fiber art a renaissance. Can you say more?

HP: It feels like people are returning to what they saw growing up, or what they’re discovering for the first time. Some of us didn’t grow up sewing—my mom doesn’t sew at all! But we’re learning now, and we’re turning it into something powerful. Fiber was dismissed for so long as “craft,” but that line is disappearing. You see it now at art fairs, in museums, in the market. The medium is finally being taken seriously.