I met Richmond, VA-based John Hee Taek Chae in Winter of 2021 at MacDowell, an artist residency in Peterborough, NH. Chae’s studio walls were covered with small to midsize graphite drawings. Depicted in the works were stilted scenes from nature, animals herded into clearings and blank-faced boys in Scout uniform. John worked diligently, making a drawing a day at the residency. I spoke to Chae via video where he addressed the relationship between the imaginary and westward expansion, the cowboy archetype, and his instigation of a polar bear club in New Hampshire. This conversation was edited for length and publication.

Courtney McClellan: You work in a range of media including painting, printmaking, and large-scale sculptural installation. But when I met you, you were working on a series of delicate, haunting graphite drawings of Boy Scouts. Would you talk about what led you to working on the series you were creating at MacDowell?

John Hee Taek Chae: As far as scaling down the media and going back to the immediacy of drawing, it was mainly to do with post grad school fatigue. I went through a long period of not making work. Not just because of grad school, also because of the times. I graduated 2020 and then there was Covid and uprisings, which were intense in Richmond with all the statues coming down. So, my attention was obviously elsewhere. I was also doing a lot of labor organizing at VCU.

It was a long pause and drawing was a way to just ease back in. I also considered it laying down the foundation of a new project.

CM: Tell me about the new paintings included in your exhibition at D.D.D.D. in New York.

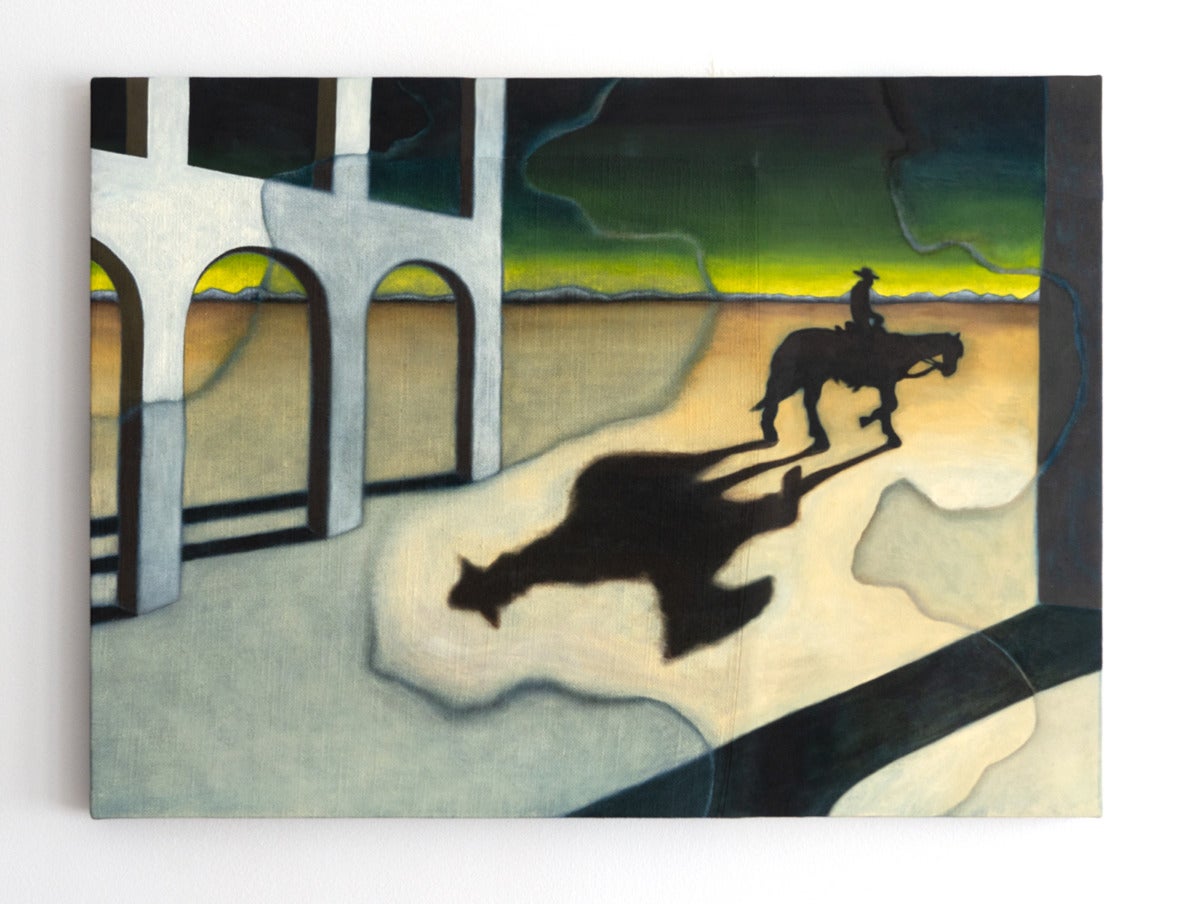

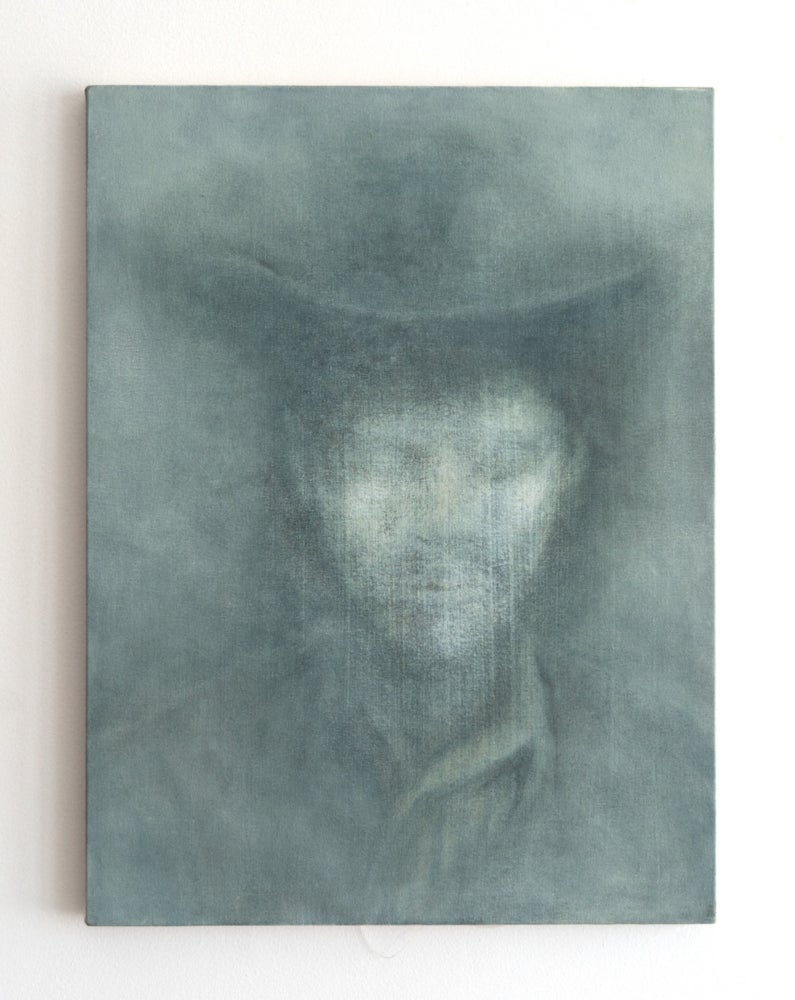

JHTC: It’s a selection of paintings, or a selection from me transitioning from drawing into painting. I started with the Boy Scouts as the motif. I was most interested in it to explore postcolonial identity, but also this fear of mutually exclusive identities. Or, being put into this place in which you must take sides. And then what happens when you are being put into that situation, but you have adopted the tools of colonialism yourself, or internalize them and the fear of repeating that sort of violence or repeating that sort of mindset towards each other, but also towards nature. I think there’s obvious segue between that and cowboys and settler colonial narratives.

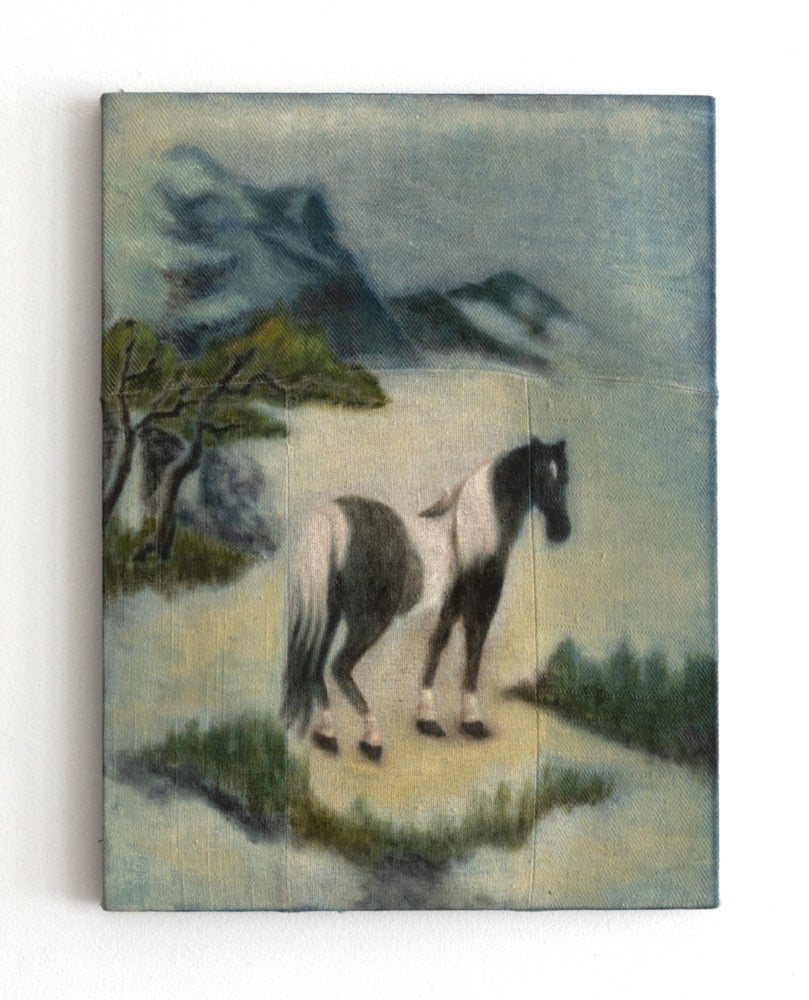

The horse became kind of a symbol of desire for domination, but also visualization, but also mystique. I was painting them small to reference carriage house paintings, or mantel piece paintings. But also, they’re copies of Giuseppe Castiglione, an eighteenth-century Italian Jesuit missionary who served as an imperial court painter for three successive Qing Dynasty emperors.

CM: You talk about complicated feelings related to landownership, you even address historical and contemporary homesteading as a form of cosplay, particularly from your vantage point as a Korean American. Can you say more about that?

JHTC: I was born in Colorado, but I moved to Seoul, South Korea, when I was eight, and then was there until I was 18. Then I lived in Baltimore and New York. It’s only the past five years that I’ve left these urban centers. Outside of the urban center, the immigrant experience is much more legible. And not just in the way that other people see Asian American bodies and where they can have presence in the country. But also, the first time I went skinny dipping, canoeing – all these things happened to me later as an adult at 26 or 27. When I was younger, I rode a horse once where someone was holding on to the reins. I can’t remember the first time I really saw the Milky Way. You realize in some ways, how provincial you were, how deprived you were of these basic human experiences. I have more of those connections now that I’m in Virginia. It feels very foreign to me because I have so much space and can grow vegetables and have a huge lawn. And I work on a motorcycle. These moments where I look at myself and kind of like, “Who the hell is this?”

I think when it comes to the painting, I guess I’m trying to think of the right word. It’s like different aesthetic languages and by mutating them together it helps me get closer to this contradiction or this feeling. The operative words are always fears and desire for me right now when it comes to even talking about identity.

CM: I feel like your work meets the imaginary with great caution. Imagination is often touted as creative and exclusively positive. Of course, imagining is part of making art. But imagining can also be the beginning endless expansion, “discovery”, or colonization. How do you see the imaginary or the act of imagining in your work?

JHTC: Actually, your question was revealing to me as far as what I was doing. I never realized I was being so cautious about imaginary or imagination, but I think it’s true.

In the context of this country, there’s always a zero-sum game mentality. It’s always individualized. It’s hard for me to imagine something else. You have your own the property, you have to work it yourself, and you reap the benefits. Or, you hire somebody. It’s not communal in any way. And those traditions obviously exist, but competing narratives are always being repressed or extinguished.

That’s the other thing about wanting to go back to this settler colonial narrative motifs as a way for me to do my own study about what’s happened in this country. I read Iyko Day’s Alien Capital: Asian Racialization and the Logic of Settler Colonial Capitalism (2016) and it was really important for me because she helped me re-understand the experience between alien settler and native, the logics of colonialism and capitalism and why you get racialized in a certain way. And obviously that logic is not consistent.

CM: This exhibition is making me think of a few other recent works addressing the myth of the West as it relates to people of color— particularly the recent film Nope (2022) written, directed and co-produced by Jordan Peele, or Silent Spikes (2021) by artist Kenneth Tam. Why in this moment are we contending with the cowboy archetype?

JHTC: It’ll always be there when it comes to the American experience. I saw Nope, and it was very entertaining for me. There are things being hinted at, but I haven’t done enough research to dissect the film and confirm whether Jordan [Peele] is thinking similar things as I am. But I think the imagery is always powerful whenever you see POC bodies in Western clothing, brings me to a more direct reference for me.

For me, it’s more like I’m not attracted to [cowboy imagery] because I don’t necessarily want to be. I’m attracted to it because I’m afraid of doing similar things if I follow my desires. I haven’t figured out how to include it in my work: what’s not present there? What’s the figure opposite? The cowboy, right? I’m historically the one that’s not present. But now coming into a position in which– you could become the cowboy now. I could own this land and buy a gun. Those are the themes that I’m more interested in.

CM: Lastly, I wanted to ask about your methods, research, and process— particularly things that happen outside of the studio. You had a sort of bucolic polar bear club in New Hampshire. You would go at sunrise and jump in the nearby pond every day. I was too chicken to ever go. How did this ritual influence your studio practice?

JHTC: Back to being really attracted to this experience that I had never had, and then also having an addictive personality, so I needed to do it every day.

I’m sure a lot of it was novelty, part of it was performance, I don’t want to get too definitive. I just liked doing it. I like to make work in the morning and I don’t do project-based, it’s a daily practice. I kind of let the work develop over time, without necessarily these culminating points.

I always just try to follow what the stronger emotions are. Cringe for me was a big feeling when it comes to identity. I see certain images, then I should follow that instinct and figure out why I feel like it’s cringe. When coming up with references for the work, follow the feeling.

Become a member or make a tax-deductible donation below.