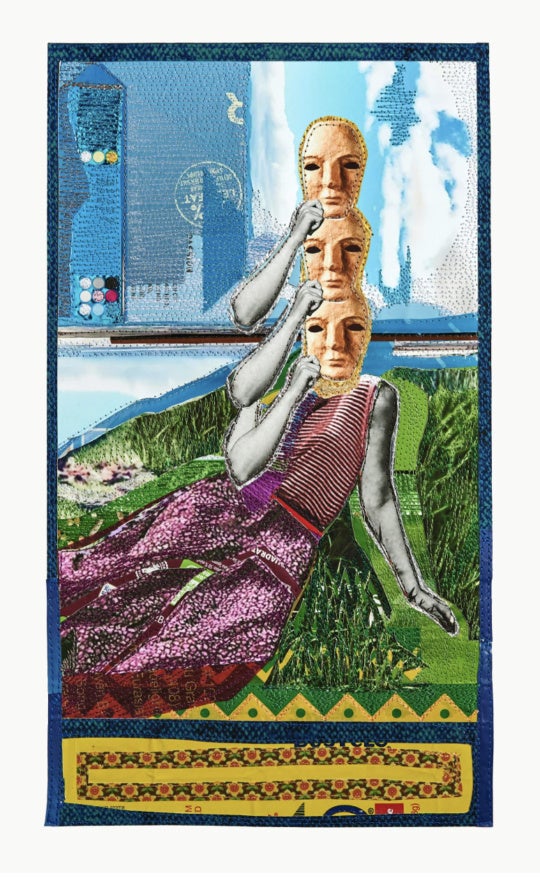

Household objects don’t have memories, but if they did, what a tale our sheets could tell: sex and dreams, illness, despair, joy, conflict, connection, loneliness, even birth and death. We like to imagine that life consists primarily of what we accomplish in the great wide world, but a bed is often the site for the most intimate and significant moments in our lives.

Atlanta artist Marcy Starz uses the resonant material of thrift-store bed sheets as her canvas in the exhibition “Cold Comfort,” on view at Beep Beep Gallery through September 19. The artist has seemingly imagined the sheets as a sort of mute witness, stretching the material as her canvas and then painting dreamlike images. Some of the figures are evocatively semi-transparent, highlighting the weird interstices between painted image and printed surface. There’s a touch of melancholy to almost any domestic object no longer in use, and it’s especially true here. The end result suggests not just a new creation from the artist but the release of something left behind from the sheets’ earlier role.

The repurposing of old sheets into quilts is referenced through the repeated use of the familiar Lone Star pattern, a central six- or eight-pointed star made up of diamond-shaped pieces of fabric, one of the oldest and most recognizable patterns in American quilting and a recurring motif in Starz’s work. In pieces like End of the Line, in which the figure of a girl sits curled in an armchair anxiously holding a telephone; Clamour, which depicts two intertwined figures standing with their arms locked; or Partners with the same two figures interlocked but standing back to back, Starz evokes moments of domestic uneasiness, conflict, and dysfunction. Her figures are naturalistic, but her brushwork is loose enough to make a curious parallel with the brushwork of the printed bed sheets. The artist of that much earlier floral pattern is anonymous, and the material has gone through many lives since then, but the surreal, transparent figures make us weirdly conscious of the convergence; this is the work of two painters.

While the Lone Star pattern is one of the thematic threads of the small exhibition—it’s repeated or referenced in nearly every piece, and a small installation in the gallery’s back room deconstructs the pattern with unpainted diamond-shapes radiating outwards from the familiar star—the show’s strongest images are actually in circular works where the artist abandons the device. Conflict Management I depicts two snarling wolves set against the placid backdrop of patterned flowers, recalling the conflicting human couple and suggesting the animalistic conflict and violence that can often occur against the seemingly placid backdrop of domesticity. The wolves reappear with less success in Conflict Management II. They seem less ferocious in the second work, more evenly and less evocatively lit; they’re more docile, their snouts snubby and almost cute.

That kind of latent threat is similarly aimed for but missed in Snake in the Garden, which depicts a serpent, the diamond-shaped pieces arranged into an arrow-shape; a vague and semi-formed dream loses its power and immediacy in specificity and retelling.

On that note, easily the most powerful and creepy works in the exhibition are two circular pieces Unoccupied I and Unoccupied II, which simply depict two plain wooden chairs. The first has a swath of semi-transparent paint, dripping like body fluid from the top. A starkly painted shadow makes the image seem to pop out dimensionally and also makes us conscious again of the interplay of flat painted surfaces.

Starz is a young artist, a 2009 graduate of Kennesaw State University, and the show, in which she fully explores a simple but evocative idea in a small series of works, feels compact, but accomplished and complete. She’ll be an interesting Atlanta artist to watch in the years to come.

Andrew Alexander is an Atlanta-based critic who covers visual art, dance, and theater.