In her groundbreaking 1971 essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?,” Linda Nochlin describes how social and structural barriers have long kept women from being included in the traditional canon of art history. While Nochlin’s primary scholarly focus is on the nineteenth century, her arguments can easily be applied to the story of twentieth-century Modernism and its emphasis on formalism, medium-specificity, and individualism. In Hinge Pictures, currently on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans, curator Andrea Andersson brings together the practices of female artists challenging this history now. Looking back at pivotal movements like color-field painting, Bauhaus design, and Constructivism, the artists on view reframe the legacy of Modernism while emphasizing the political implications of abstraction.

The exhibition takes as a conceptual starting point Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even (1915–23). The work, which is in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is a painting on clear glass and metaphorically depicts the titular bride dangling above a crowd of suitors. The bride and her bachelors all appear as abstract jumbles of industrial materials. The body is center-stage, albeit distorted. Displayed in the round, Duchamp’s see-through work is like an overlay, a transparency that can be used as a lens to alter the so-called real world behind it. Duchamp skirts both didactic representation and complete abstraction in favor of a murkier middle-ground. In his Green Box, an assortment of documents and sketches first published in 1934, the artist hints at this possibility of bringing artistic abstraction out into everyday life:

Perhaps make

a hinge picture.

(folding yardsticks, book….)

ADVERTISEMENTdevelop

the principle of the hinge

in the displacements

1st in the plane 2nd in space

…

perhaps introduce it

in the Pendu femelle

The Hinge Pictures catalogue opens with this quote, and the exhibition is centered on this conception of displacement—of people, of ideas—and how it has defined what scholars, curators, artists, and museumgoers think of as Modern art. For Andersson, the notion of the Pendu femelle—the “hanged woman,” the female artist on display—allows for a deeper dive into Duchamp’s theory and a broader reassessment of art history. While the exhibition’s concept can feel overly erudite and the connection to Duchamp is sometimes tenuous, the largest takeaway from Hinge Pictures is a fresh understanding of how we all—both artists and viewers—are implicated in the history of abstraction. At the CAC, eight artists explore this entanglement by investigating the relationship between abstract formalism and the human body.

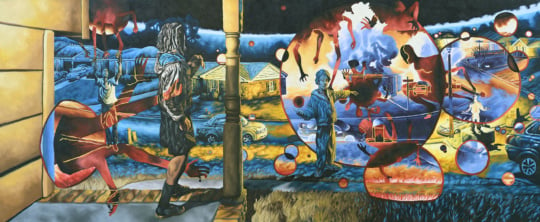

In a group of works installed on the museum’s second floor, Tomashi Jackson addresses the pernicious ways in which the language of color theory, specifically in Josef Albers’s Interaction of Color (1963), mimics the racialized language used in cases like Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954). In a 2016 interview with Risa Pulea for Hyperallergic, Jackson listed some of these terms: “colored, boundaries, movement, transparency, mixture, purity, restriction, deception, memory, transformation, instrumentation, systems, recognition, psychic effect, placement, quality, and value.” Jackson’s works in Hinge Pictures are part of a series examining the ways in which the infrastructure of public transit—or lack thereof—in Atlanta and surrounding counties has served to surreptitiously enforce segregation. In Interstate Love Song (2018), Jackson attaches thin strips of transparencies printed with photographs of white protesters—upset over the expansion of urban train lines into historically segregated suburbs—onto a storefront awning. A related photograph installed nearby shows a man shrouded in a knit blanket. A city scene is digitally inserted across the textile, a sharp contrast with the winding Chattahoochee River in the background. The works question how public space is divided by line and color through infrastructure.

Similarly, Adriana Varejão investigates how defining and distinguishing minor differences between colors has been used to fortify the construction of race in Brazil. In her Polvo series, Varejão uses 136 different skin-color descriptions taken from a 1976 census in the country to create individual pigments that are then applied to color wheels with collections of browns and beiges. In this same series, the artist uses these varied colors as flesh tones in a collection of self-portraits, echoing how minor distinctions between hues have been used to create and enforce racist ideologies in Brazil and across the world. (In the United States, the nefarious legacy of the “brown paper bag test” is one among many pseudo-scientific uses of color to define identity and enact racist policies.) Varejão’s biting commentary on colorism feels relevant, but the individual works don’t feel as compelling as they could be with greater consideration of how census respondents might have related to this act of self-categorization.

Claudia Wieser’s installation on the CAC’s first floor takes inspiration from the German idea of the gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art incorporating all media, a concept embraced by the architects of the Bauhaus School in Weimar Germany. Including full-height wall decals of film stills, architectural details, and design objects and wall sculptures made from tiles and mirrors, the work looks back to the human-centered approach of Modern architecture. By literally reflecting the viewer’s presence into the work itself, Wieser hints at how our lives are shaped by the ways in which we move through the built environment and by the omnipresence of design in every object around us. The tension between form and function is also present in Erin Shirreff’s large-scale prints of collaged images of cast concrete sculptures. The sculptures depicted look like tools or pieces of furniture that have been rendered dysfunctional, and the prints are folded and curled to turn the pieces of paper into sculptures themselves.

fishing rods, super 16mm to HD video, color, sound (10 min.), 14 by 28 by 37 feet.

Sarah Crowner’s architectural intervention in the galleries includes a platform fitted around the CAC’s curved spiral ramp. The shape of the gallery, built around this cylindrical walkway is echoed in Crowner’s curved paintings, which are patched together from pieces of canvas painted in black, blue, purple, and orange. Here, Crowner asks viewers to examine the nearly unseen handiwork, a contrast with her Minimalist forebears who sought to disguise all evidence of the artist’s touch. From the vantage point of the raised platform, the fragmented blocks of color are immersive and striking, and her installation feels like one of the best uses of this narrow slice of exhibition space in recent memory.

The standout work in Hinge Pictures is Ulla von Brandenburg’s Two Times Seven (2019), which creates a portal lined by large pieces of brightly dyed fabric draped like stage curtains. Stretching all the way to the ceiling, Two Times Seven feels like entering another dimension, one where reality is shifted by a continual process of unveiling. At the end of von Brandenburg’s installation is a projected video showing patterned fabrics being pulled back to reveal seemingly endless pairings of stripes, plaid, and floral designs. This work is a reminder of the textile and costume designs of Russian Constructivist artists such as Liubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova, who were integral in that movement’s conceptions of labor equality and proletariat revolution. Screens also play a part in Julia Dault’s paintings, in which the artist layers patterns and colors to highlight what is not immediately evident. In Intergalactic (2018), Dault covers a colorful composition of stripes with a thin, cloudy gray, leaving only a small circle through which the bright patterns beneath are visible. Likewise, the curved lines of Dault’s sculpture Black Widow (2018) are based on the industrial plumbing systems that are hidden behind walls. With these works, Dault suggests taking a closer look at the systems that we, as a society, have chosen to cover up.

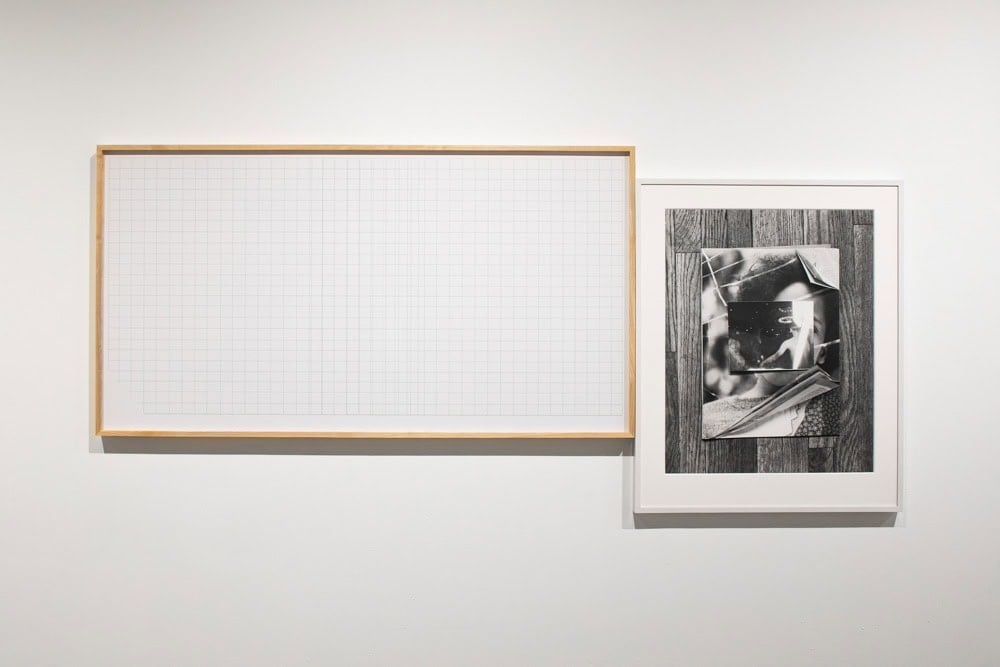

Andersson’s interpretation of the “hinge picture” is most felt in the possibilities offered by photographs from Leslie Hewitt’s Riffs on Real Time series. By arranging vintage photographs, magazines, and other ephemera into still lives, Hewitt creates a space for cross-temporal contemplation, a chance to understand how accumulations of events—and our individual interpretations of them—affect our current circumstances. In Riffs on Real Time with Ground (Green Mesh) (2017), Hewitt presents an image of a photograph seemingly from a party placed on top of the face of a young girl shown on the cover a dog-eared booklet. Set atop Hewitt’s wooden studio floor, the pairing suggests that these disparate scenes are, through human nature, connected—and that there may be pages and pages of connections hidden in the pile. The still life is shown next to a photographic reproduction of an empty grid, a place where we might draw out these interdependencies.

If Duchamp’s writing in Green Box centered around the blending of art and everyday life, the works on view in Hinge Pictures also suggest how reconsidering this relationship might open up the legacy of Modern art beyond the largely white, largely male lineage which has long been used as a barometer of taste and cultural relevance. Ultimately, the exhibition leaves Modernism not as something to be dismantled or erased but rather something to be unpacked and rearranged so that it might better serve more of us today.

Hinge Pictures: Eight Women Artists Occupy the Third Dimension is on view at the Contemporary Arts Center in New Orleans through June 16. An accompanying catalogue, produced in collaboration with Siglio Press, will be released at Printed Matter in New York on May 16.