In recent years, the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Jacksonville, Florida, has put considerable emphasis on education through imagery, art, and outreach. As a cultural resource of the University of North Florida (UNF), the museum, through various programs, has been focused on encouraging a broad audience (locally and regionally) to be inquisitive advocates and appreciators of the arts. In its downtown setting, the museum shares a large block with the city’s main public library; JEA, the not-for-profit community-owned utility company that serves Jacksonville; the historic gathering place Hemming Plaza, a large park recently approved for restoration and new management; and a recently installed year-long public sculpture walk in Main Street Park. These diverse neighbors demonstrate the need for a cultural institution whose exhibitions and programming offers broad public appeal.

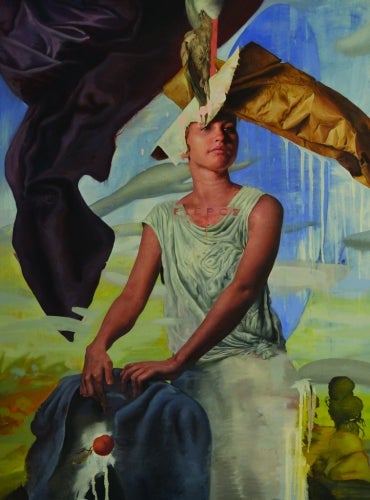

The newest exhibition at MOCA, “Get Real: New American Painting,” curated by Ben Thompson, has been in development roughly since 2011. On view through January 4, it features 61 paintings by eight artists—Haley Hasler, Jason John, Andrea Kowch, Bryan LeBoeuf, Jenny Morgan, Kevin Muente, Frank Oriti, and Kevin Peterson—who present a look at the current state of American figurative painting that has significant ties to realism and its derivatives, “narrative portraiture and social, psychological, and magical realism.”* Artist Jason John, assistant professor of painting at (UNF) is also available to the public (in person and streaming live) throughout the exhibition, painting in an onsite studio at MOCA for the “Jason John Studio Experience.” His in-progress works reveal his editorial approach to painting, as he continually adjusts the relationship of the figure to the environment. He utilizes not only large-scale photo references, but also other historical references (from antiquity armor to renaissance masters) to develop his images that attempt to channel the charged friction between realism and abstraction.

The artists in “Get Real” hail from a variety of locales with differing artistic training but share a clear motivation to depict the human figure. Individually and collectively, the works by these artists have the capacity to instruct, guide, appeal, question, and contend.

Consider the exhibition title “Get Real,” a directive to stop being unrealistic, or to stop living in a dream world. This phrase could be directed towards the viewer, the paintings, the artists, or even towards the authority of painting. Perhaps it is all of the above. For the viewer it could be a call to recognize the current position contemporary figurative work has, and to consider its relevance. For the paintings and their producers, it is a declaration of style, the degree to which they adhere to realism taking into consideration craft, illusionism, mimesis, appropriation, symbolism, narrative, etc. As for the authority of painting, to “get real,” it could be a suggestion to consider not only the historicity but also the contemporary expectations of the media. To be realistic about the fact that despite whatever manifestation painting currently explores it has license to appropriate any style, image, structure, or definition it can trace to its lineage.

Considering this operative, it is apt that several works in the exhibition are categorized as magic realism. In a way, painting is like a character or subject in magic realism that just seems to live forever, beyond that of a natural timeline, spanning generations, styles, references, and histories. Due to the narrative structure of magic realism, this is completely conceivable. In this genre, intimate highly rendered details become real in ambiguous settings. Juxtaposing Byzantine-like elaborate and carefully chosen details churning in strangely vague histories, Andrea Kowch’s stony cast ofall female characters are silent in their stories. Pressed lips, trained gazes, and practiced composure keep her women focused, while intensity swarms around them. In Jenny Morgan’s work, she counters finely rendered details with destructive blurred brushstrokes or glitches of abstract shapes and elements, or she contradicts sensuous flesh tones as they gradate, escalating to electric greens, reds, and yellow hues.

Overall, the artists and the works selected offer alternative options for interpreting realism in painting. The figures are diverse in their engagement with their surroundings and/or other figures, their mood, attire, age, and projected narrative, but they are less diverse in their ethnicity. By presenting the figure as the dominant subject matter (there are also animals, landscapes, victuals, and abstract elements) the works engage imitative inquiry, or learning through mimicry. Arguably, human socialization and behavioral patterns are adapted from mimicking. Many of the artists in this exhibition reference and directly borrow from the Western canon of figurative painting. By doing so, they are propagating the styles, trends, and iconography of this tradition. Consequently, the viewer is invited to an exchange, to connect or to react to the depicted scale, expression, history, accessories, and identity of the characters. This exchange has an immediate effect on the interpretation of the figure based on viewers’ personal associations. The result: the museum has effectively built a show of people, for the people, by people.

* Ben Thompson, Foreword. Get Real: New American Painting exhibition catalogue, p. 10. Agility Press: Jacksonville, FL, 2014.

Lily Kuonen is an assistant professor of art at Jacksonville University in Florida. She is a native of Arkansas, where she was born in the kitchen of her parent’s house.

48 by 33 inches.