The twentieth century in America would undoubtedly look very different without Garry Winogrand having documented it. His images of protest movements, interracial couples, the dying days of the Fifties, and economic uncertainty coexisting with America’s native ebullience complicated the nation’s vision of itself.

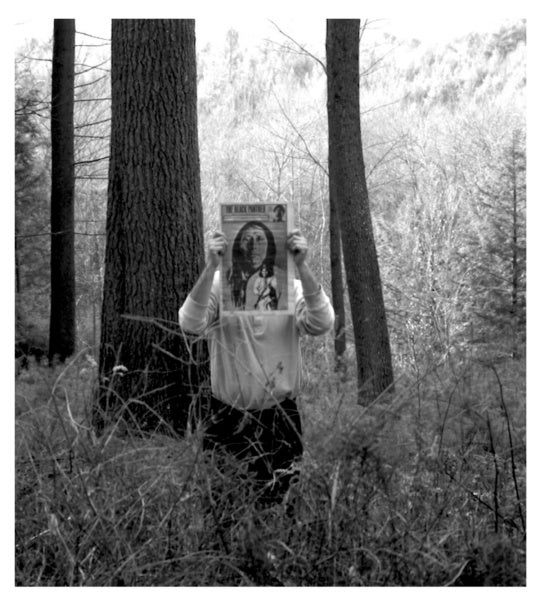

In his incredibly revealing images, Winogrand offers remarkable access and detail. His camera hovered over couples kissing on the street, amid the violent eye of rallies, and in huddled groups of businessmen, always impossibly close and intimate. Somehow, Winogrand’s camera was there, arresting what feels like humanity’s throbbing, coursing lifeblood. “Everyone’s dancing,” marvels photographer Matt Stuart in Sasha Waters Freyer’s documentary Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable, paging through image after image of young girls cuddling like puppies on a park bench, a group of women commandeering a New York sidewalk like generals, each depicting the roil and movement of life so vibrantly that you feel in the thick of these kinetic, buzzing moments.

Winogrand also found poignancy in isolation and solitude, as in his image of a sailor walking on a desolate New York boulevard, utterly alone in the twilight. Symbolically speaking, Winogrand often put a representative of himself front and center in his photos. Because of the street photographer’s perpetual sense of isolation and invisibility, Winogrand identified with the body lying in a ditch on a busy L.A. street captured from a moving car and the clown being chased by a rodeo bull; horror and humor coalesce in the human condition and in Winogrand’s work. Or as one of the documentary’s many talking heads, Mad Men creator Matthew Weiner, says about Winogrand: “[To] see something through someone else’s eyes and feel less lonely” was his ultimate mission.

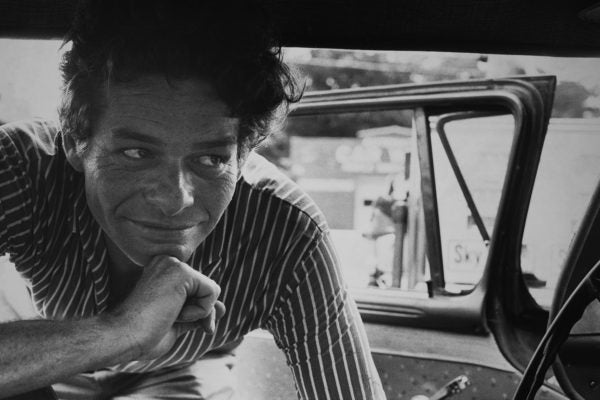

A tour through Garry Winogrand’s unique sensibility and, consequently, a changing America, the film charts a career now enshrined in the canon of American photography but which was, like most artists’ lives, tentative, changeable and difficult in the living.

His longtime champion John Szarkowski, the Museum of Modern Art’s photography curator from 1962-1991, said Winogrand’s vantage “almost persuades one that I stood where he stood.” And yet, nothing about Winogrand’s destiny as a great American photographer seemed inevitable, Freyer’s doc attests. The child of Jewish immigrants, he was, according to Szarkowski, “a city hick from the Bronx.” He attended Columbia to study painting but then discovered the school had a camera club. He joined it and found his calling. After his training, Winogrand chafed against his initial role as a commercial photographer illustrating stories for magazines. Reluctant to be confined to the glossies, he willed himself to become a free agent, no longer yoked to the requirements of a journalist’s story.

A host of luminaries—other photographers, curators, Winogrand’s wives and contemporaries—weigh in on both the photographer’s signature “look” and his legacy, including photographers Laurie Simmons, Matt Stuart and Susan Kismaric, biographer Geoff Dyer, and gallery owner Jeffrey Fraenkel. The documentary walks us through some key moments in Winogrand’s career: the Cuban Missile Crisis, which shook Winogrand to his core and instilled a deep pessimism about American life; the 1967 exhibition New Documents at MOMA, curated by Szarkowski, which featured photographs by Winogrand beside those of Diane Arbus and Lee Friedlander, offering an utterly original take on national identity; and his series The Animals, which gives a keyhole view into Winogrand’s post-divorce single-daddy-dom and endless trips to the zoo. He used those parent-child outings as a chance to document animals surveying humans and vice versa, along with the strange melancholy that results from such an interaction. That angst is perhaps best encapsulated in a tragic close-up of a human hand reaching to drop peanuts into the outstretched pipe of an elephant’s trunk—a statement of estrangement even in connection.

Though the assembled experts unanimously acknowledge Winogrand’s formative imprint on the American scene, divisions arise to complicate a purely heroic account. None is so stark as the philosophical split that opens up between male and female curators, photographers, gallerists, and writers when discussing Winogrand’s controversial 1975 artist book Women Are Beautiful. Filled with occasionally leering images of women, captured like exotic, available specimens on city streets, the series appears to some viewers as a continuation of Winogrand’s fascination with the human animal and an unapologetic celebration of the female form. The women surveyed tend to be less generous. “From my perspective, Women Are Beautiful is a very bad book,” intones SFMOMA curator Erin O’Toole. At the height of the women’s movement, when artists like Laurie Simmons admit to having experienced routine, constant street harassment, having a fellow photographer putting those same toothsome, braless women under his lascivious gaze looked like more than bad timing. Winogrand appeared out of touch, unable or unwilling to read the zeitgeist. The moment marks a necessary break from the hagiographic tendencies that often hinder these kinds of biographical docs, acknowledging the flaws and missteps of the film’s subject.

Near the end of his life—Winogrand died early, at the age of 56 in 1984—health issues meant he often photographed at a distance, taking in the Los Angeles of the Eighties from inside a car, no longer that vibrantly on-top-of-the-action player of his New York street photography days. That new vantage echoed his own fading from the game of life, the ultimate estrangement of a photographer who strives to capture the essence of life but inevitably misses the mark in that impossible task. And as his career sunsetted, Winogrand continued to shoot obsessively, even if he never edited or developed his shots, accumulating some 347 rolls of undeveloped film as if he was hanging onto life, soaking it up the best way he knew how, through a viewfinder.

Garry Winogrand: All Things Are Photographable is screening at Midtown Art Cinema in Atlanta through November 22. The documentary will be screened at the Speed Art Museum in Louisville on Saturday, December 8 at 3 pm.