“The camels have come!” or so declared the front page of Galveston’s Civilian and Gazette Weekly on Tuesday morning, October 26, 1858.[1] The arrival of the Thomas Watson at Parson’s Wharf marked the second supply ship in two days, delivering a total of eighty-nine camels to the Gulf Coast. The reporter further detailed the encounter between Galveston’s boisterous locals enchanted by the “strange visitors.” As strange as it may be, these were not the first camels to set foot in Texas. In May 1856, a little over thirty camels arrived in Indianola, TX, as part of the US Army’s “Camel Corps,” a nineteenth century experiment conducted by the Department of War to employ camels and dromedaries for land surveying, transportation, and other general military labor use.[2]

Convened by anthropologists and visual artists Myriam Amri and Xitlalli Alvarez Almendariz at Friends Gallery in Houston, An Act to Prohibit Camels and Dromedaries from Running at Large resurrects the presence of the displaced camels through historical archival documents, material objects, and multimedia works. The installation is presented as an open, interactive archive, allowing visitors to physically engage with the deeply researched bibliography compiled by the artists. The archival materials span diaries and journals, letters and notes, photographs, and maps from US officers and Camel Corps personnel as well as published scholarship on the topic in the form of books and articles. This makeshift archive synthesizes the broader social and visual history of the experiment, revealing a unique historical conjuncture between the US Gulf Coast and the Gulf of Tunis.

Amri and Alvarez Almendariz critically engage with notions of access and legibility as it relates to procedures of research, collection, display, and knowledge production within institutional settings. Their archive includes a reading room, two display cases, and designated projection space, assembling familiar objects and architectures that mediate knowledge transfer in archives and museums.

The reading room contains two tables, each covered with original and printed reproductions of research documents. A third table offers an area for visitor interpretation and reflection. Among the many archival materials, the correspondence between US Army and Navy officials reveals the camel project’s most important sponsor, Jefferson Davis. Davis first proposed the idea to Congress as a Mississippi Senator in 1851 to remedy the logistical and economic challenges of transporting supplies across the newly acquired Southwestern territories following the Mexican-American War.[3] Not until Davis rose to Secretary of War by 1853 would Congress agree to appropriate $30,000 for the importation of camels and dromedaries to Texas.

Soon after, Jefferson appointed Major Henry Wayne to head the expedition along with Naval Lieutenant David Dixon Porter. The USS Supply arrived in Tunisia in August 1855 where they procured two to three camels, then continued on toward Crimia, Malta, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt. The Supply finally returned to Indianola with thirty-four camels and five cameleers.[4] Wayne then journeyed to San Antonio, and eventually to Camp Verde where the camels were permanently stationed until a major cross-country expedition in 1857.

One of the primary concerns of the open archive is to shed light on the geopolitical context and broader economic network of the Camel Corps. Three graphic lines extend across the gallery floor, mapping the trail of Lieutenant Edward Beale, of whom was assigned two tasks: to survey a transportation pathway from west of the Mississippi Valley to San Francisco and to prove that camels and dromedaries could adequately adapt to the climate and geography of the Southwest.[5] Sandy hoofprints appear along these ‘routes’ and creep up the gallery wall, visualizing the camel’s spectral path. Fragments of period drawings and prints depicting Lieutenant Beale’s excursion illuminate the floor beside. However, Davis was interested in far more than demonstrating the physical prowess of camels. Historian Kevin Waite demonstrates the role of the Camel Corps within Davis’ larger political project of westward expansion that sought to extend the slaveholding southern states to California through the construction of a transcontinental railroad.[6]

Operating as artist-archivists, Amri and Alvarez Almendariz trace and recover these entangled histories of the failed Camel Corps experiment with US imperialism, the African slave trade, and ideologies and myths of American frontierism. One folder contains printed articles investigating the relationship between camel cargo ships and slave smuggling. Until the Camel Corp’s official dissolution in 1866, supply ships continued to procure camels along the Mediterranean and Africa. This enterprise served as a convenient ploy to engage in the illicit African slave trade. Included within the archive is the 1955 article, “A Cargo of Camels in Galveston” by Earl W. Fornell, which uncovers the aforementioned ship Thomas Watson that arrived in Galveston in 1858, also engaged in human trafficking.[7]

The installation uses casework to bring attention to the interplay between visibility and opacity within institutional models of display. The interior surfaces of two display cases placed in the center of the gallery are nearly obscured. Only a small circular cut-out shows video footage filmed by the artists inside. One case contains a film of the bones of Said, known as “the last camel,” whose skeleton remains on view in the National Museum of Natural Science’s Hall of Bones. A video of the grassy marshes of the Sims Bayou, a known stop along the camels’ long journey, loops in the other case.

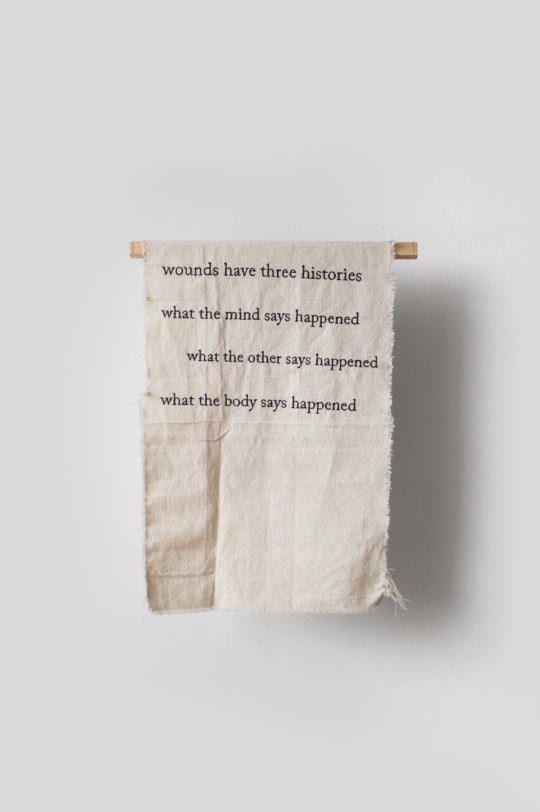

At the far end of the gallery is a curtain-lined wall space for viewing a short motion picture that premiered the night of the exhibition opening. Using an analogue opaque projector, Amri layered reproductions of original drawings, food and ration logs, and red transparency paper. Like a living collage, the motion picture animated and retextured the immaterial afterlives of the camels. Sounds of native Houston nighttime insects played throughout the performance, while a camel’s shadowy outline lurked across the projection as an eerie apparition.

The images illustrated the speculative nonfiction ghost story narrated by Alvarez Almendariz, a haunting revenge tale adapted from the personal journal kept by Lieutenant David Dixon Porter but told from the perspective of a camel on the USS Supply. The story draws on the folklore of the Red Ghost, the largely Arizona-based legend that evolved from the perception of camels as wild, unpredictable, and foreign. Within the settler American cultural imagination, the camels manifested as racialized subjects and objects of fear. Through embodied roleplay, Alvarez Almendariz reimagines and reframes the colonial narratives of conquest and control that inform the Red Ghost stories.

Amri and Alvarez Almendariz’s project seeks to democratize the archive and encourage tactile engagement with archival holdings to open noninstitutional avenues of research-based inquiry and interpretation. Speculation is used as a means of remembrance to trouble the enduring myths and narratives rooted in a colonial imaginary. An Act to Prohibit Camels and Dromedaries from Running at Large thus unsettles and critically examines the ambiguous relationship between archive, history, and memory.

[1] Civilian and Gazette. Weekly, vol. 21, no. 30, Ed. 1 Tuesday, October 26, 1858.

[2] Vince Hawkins, “The U.S. Army’s ‘Camel Corps’ Experiment,” On Point 13, no. 1 (2007): 10.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 11-12. For a more in depth study on the camel drivers see also: Gary Paul Nabhan, “Camel Whisperers: Desert Nomads Crossing Paths.” The Journal of Arizona History 49, no. 2 (2008): 95–118.

[5] May Humphreys, Stacey, Edward Fitzgerald Beale, and Lewis Burt Lesley. Uncle Sam’s Camels. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard Univ. Press (1929), 18.

[6] Kevin Waite, “Jefferson Davis and Proslavery Visions of Empire in the Far West,” Journal of the Civil War Era 6, no. 4 (2016): 536–65.

[7] Earl Fornell, “A Cargo of Camels in Houston,” The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, 59 (July 1955-April 1956): 40-45.