Haifa Street and Khark in Baghdad in 2007, 2007; ink, watercolor, and gouache on paper.

Steve Mumford’s War Journals, 2003-2013, on view at the Frist Center for the Visual Arts in Nashville through June 8, largely comprises collected “field drawings”—watercolor and gouache sketches—by the New York-based artist, who, armed with a press pass from Artnet.com, was embedded with troops in Iraq. Over a series of visits, he worked in locales ranging from war zones to occupied areas. As sensitive and observant sketches, they create a portrait of the artist as well as the land, the people, and the complex socio-political situation faced by all sides.

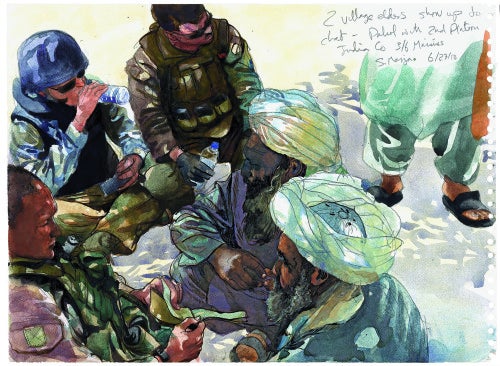

Mumford’s field drawings are described within the show’s accompanying pamphlets and wall texts as “straightforward impressions with little editorializing.” Yet within the exhibition’s printed materials, Mumford himself is quoted as saying that “if photojournalism captures a decisive moment, making a drawing is more about lingering in a place and editing the scene in a wholly subjective way,” which allowed him to “[slow] down the war” through personally filtering events. This paradox of visual journalism—to attempt to portray truth by depicting a scene with the intent of accuracy, yet complicated by the subjective choices that goes into its framing—is not new, and Mumford faces the same challenges.

In setting up a scene, he often relies on an attention to detail—delicate stitches on a patch or the carefully rendered pixelation of “digital camouflage”—and the sense of cinematographic drama in his compositional choices hint at personal bias and narrative construction. Though largely held in check within the actual images, at times his opinions become as vocal as the expository titles he employs, engaging the work itself through narrative notations.

Drawings from his Guantanamo series especially radiate a journalist’s frustration at censorship and barriers, crossing the boundary of neutrality often seen as journalistic virtue. And yet, these moments continue to feel accurate and real: many of his watercolors reference the strict protocols given to him, with silhouettes marked “CLASSIFIED” forming white areas masked off from otherwise lush washes, while notations of “permitted view” and “redacted” express a journalistic cynicism about being forbidden to depict the prisoners themselves.

Whether outspoken or observant, however, Mumford’s intimate scenes give humanity and a sense of roundedness to a situation whose front line is much blurrier than his crisp depiction might otherwise imply: Mumford’s deep respect for enlisted military is evident in his sensitive portraits, as are his feelings towards the effects of the war and of soldiers caught in the dual roles of both occupiers and emissaries. Mumford’s journals from the time describe friendly interest from crowds towards Western culture, and choices within the exhibit often depict soldiers intermingling with Iraqis or shown as caught in the middle of Iraqi landscapes, seemingly displaced or waiting for narration to move around them.

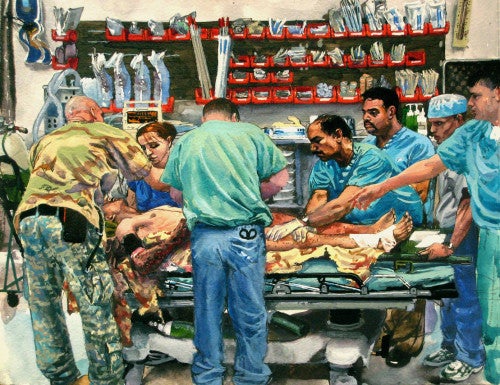

Though laden with figures and narrative action, Mumford’s urban scenes form a surprisingly quiet counterpart to his minimalist yet articulate images of military hospitals, which depict physical casualties as well as figures whose taut renderings reflect the stress of occupation and rehabilitation depicted in their faces. Mumford’s choice of monochromatic washes gives a sense of urgency and uncertainty to drawings of wounded on both sides, and a stark emotional impact to the suddenness of his line.

It is in depicting uncertainty that Mumford excels, and the single large oil painting, Empire, is Mumford at his most dramatic, showing prisoners in bright orange jumpsuits moving through dark surroundings into the belly of a transport plane. Created in his New York studio as a product of digested experience, Empire feels both immediate in content but long worked in thought. Though painted in a smooth, detailed manner as to “stylistically [evoke] the high realism and moral clarity of a traditional history painting,” Mumford’s work leaves the moral unclear and open. Despite the seemingly triumphant pose of the lead officer, the faces and postures of all involved leave the viewer with the unsettling feeling of a “victory” clouded by the unknown and unfinished, of “a conflict that seems to have no end in sight,” and of perpetual suspense. A heavy coda to an exhibition— and military situation—hung on the complications of reality, Empire rounds out War Journals’ desperate need to observe and report with an artist’s deeply felt passion.

M Kelley is a Nashville-based “maker, do-er, thinker, writer” with a BFA from Western Kentucky University. An advocate for dialogue in contemporary art, Kelley is an active contributor to a variety of diverse publications and arts initiatives. Kelley curates for the project space 40AU and the collective HAUS Rotations, and works with the Platetone Printmaking, Paper and Book Arts cooperative. Hir social practice, as both artist and curator, revolves around a fascination with the complexities of communication and narrative; providing educational and developmental opportunities; and inviting others into collaboration, curiosity, and cross-pollination through studiOmnivorous.com.